Organoids, what are they and why are they creating revolution?

Growing cells in the lab is not a new issue. For decades, two-dimensional (2D) cell culture methods have been the basis of research and the main tool for the development of new therapies. But... are they enough to respond to the challenges of science today?

In fact, advances in science have revealed their limitations. These models are unable to fully mimic the complexity of the tissues in our body. They lack factors necessary for our body and function, such as an extracellular matrix organized in 3 dimensions, specific biochemical signals or appropriate environmental stimuli [1]. This puts limits on research and the development of new treatments, because the processes that occur in the body cannot be fully studied. In this context, three-dimensional (3D) models have been a great advance because they preserve the main characteristics of organs and tissues. In this new scenario, organoids are increasingly emerging as promising tools, but... what are they really?.

They are three-dimensional structures formed by cells that have the ability to self-organize organoids, i.e., a set of cells capable of forming a properly unified system. Imagine some miniorgans created in the laboratory. They replicate the major functional, structural, and biological features of real organs on a small scale, and approach the organization of passage from cell level to organ and complexity at the functional level [2]. Thus, they offer unique opportunities to understand organ development, study the origin of diseases such as cancers or neurological diseases, test the safety of new drugs or advance in the design of personalized therapies [3]. They also represent the future of regenerative medicine and transplants, making what is closer to the imagination today a reality.

How is an organoid formed? Key components for the design

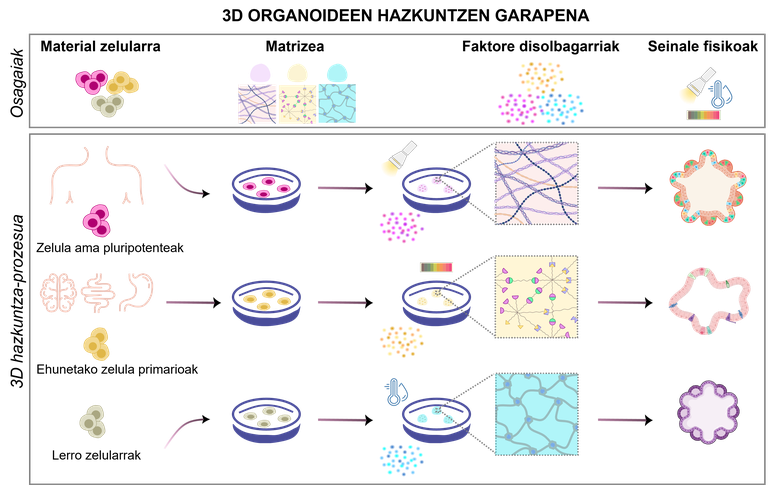

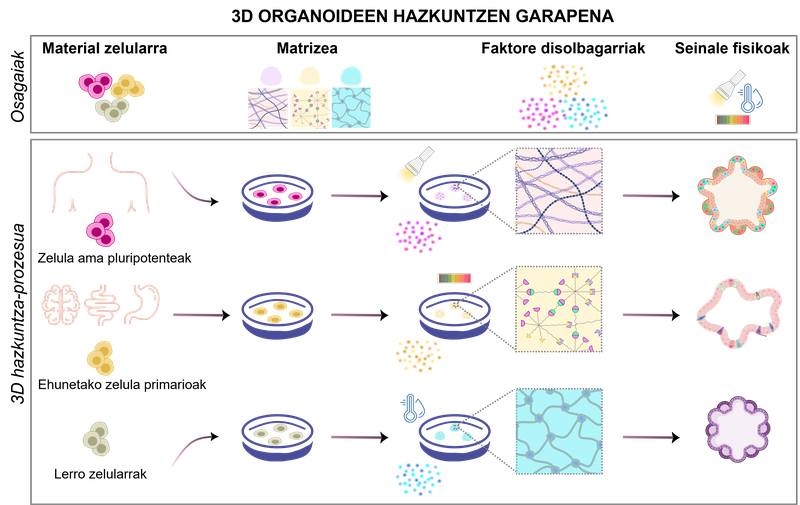

Organoids are the result of a specific process that must be properly designed. According to the objectives of the experiment, by modifying the cell types and the necessary components, there are several possible designs to meet the needs of the research (Figure 1). To do this, it is essential to take into account the following four components:

1.Material cellular

Depending on the objectives of the experiment, cells for organoid formation can be selected from a variety of sources:

· pluripotent stem cells. By modifying the culture medium used, they have the ability to renew and differentiate into any type of cell of the human body. There are two main types: embryonic stem cells derived from early embryos [4]; and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) generated by reprogramming mature cells [5].

· Primary cells isolated from the original tissues. They are isolated directly from fetal or adult tissues, thereby better maintaining their original biological properties. Mature tissue stem cells, progenitor cells, or differentiated somatic cells can be isolated from both healthy and diseased tissues [2].

· Cell lines. Pre-established cell lines in laboratories can be easily manipulated and genetically modified to test custom drugs or investigate rare diseases [6]. However, these cell types differ significantly from the in vivo model to be replicated.

figure 1. development of 3D organoid cultures. Depending on the biomaterials used and the physicochemical conditions, different types of organoids can be produced.

2.Matrizea: Cell support

The extracellular matrix provides support for the growth, development and maintenance of organoids by mechanical and biochemical signals. It mimics the natural environment of cells, providing mechanical and biochemical stimuli that influence cell growth, differentiation and organization. Currently, hydrogels are the most widely used matrices: they are polymeric networks capable of retaining a large amount of water and can have physico-chemical properties very similar to those of the original tissues [7]. Their main advantage is their adaptability; they adapt their rigidity or porosity to the needs of each organoid. In addition, they protect the cells from external stress and allow the exchange of nutrients and oxygen. In addition to hydrogels, other options such as microspheres and porous scaffolds [8, 9] are being explored.

3.Faktore soluble: responsible for organoid maintenance

Soluble factors are one of the most important components of the organoid culture medium. These molecules bind to cell surface receptors and activate internal signals to initiate or inhibit processes such as cell differentiation and/or proliferation.

In organoid culture, these soluble signals are added in the laboratory, primarily as proteins (such as growth factors) or as small molecules that can activate signaling pathways [10, 11]. But it is not enough to know what is added, it is also essential to know when and how it is added. In the body, the signals that trigger the processes are coordinated in space and time. For example, this spatio-temporal presentation is particularly important for the growth of human pluripotent stem cells and the formation of organoids composed of various cell types [12]. This controlled presentation can be achieved using various tissue engineering strategies, such as encapsulating growth factors within nanoparticles and fixing them to the cell surface for controlled release. Various nanotechnology-based methods, such as nanoimprinting, lithography, or electrospinning, can also be used to create base-membrane-like surfaces in 3D cell cultures [13-15]. By these methods, the signaling molecules are trapped in the basement membrane and released in a controlled manner.

4.Seinale physical: the movement also matters

When organoids increase, food supply and waste disposal become difficult, as they depend on diffusion. This can lead to serious problems, such as the death of central cells. And what solution does that have? Use of motion and bioreactors to evenly distribute nutrients and oxygen [16]. Bioreactors create and maintain a controlled environment for cells to grow and develop under optimal conditions. Thus, they control pH, temperature, oxygen and glucose levels with the dual objective of maximizing food transfer while minimizing mechanical stress on cells [2, 16].

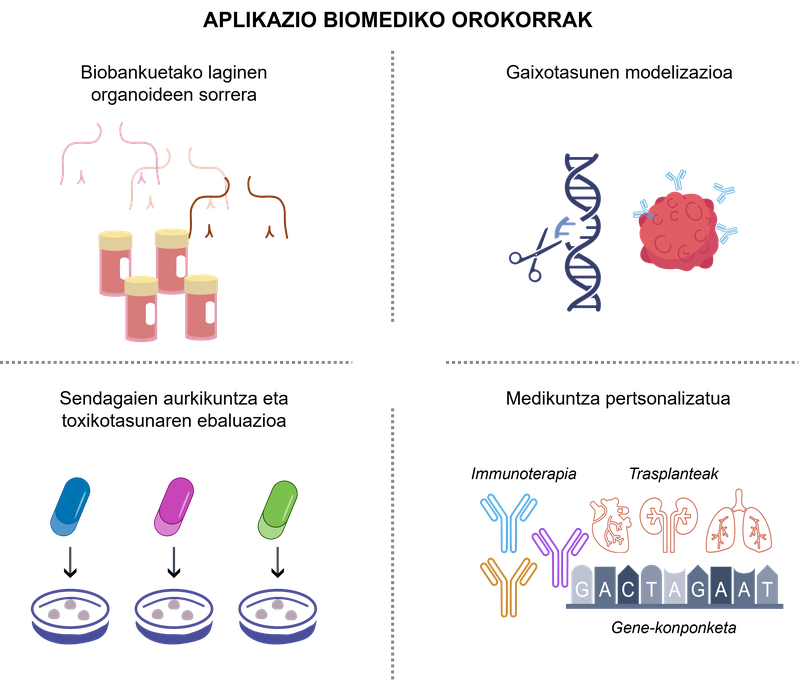

The bioengineering based on organoids has represented a new paradigm in health research, since it has allowed a more realistic analysis of the behavior of cells and an approach to clinical applications. some significant examples of such applications can be seen in Figure 2.

figure 2. [Biomedical applications of 3D organoids].

[Importance of biobanks]

The Biobank is a systematic collection of human biological samples and their associated data, created for research purposes and which allows the sharing of samples with strict quality controls. However, the samples required for organoid formation are deficient, are obtained by invasive procedures and vary widely from person to person.

Organoids make it possible to cope with the shortage of human organs: their capacity for self-renewal, their long useful life and the ability to maintain the characteristics of the tissue over time, allow the preservation and reuse of the organoids of the patients. This allows the design of personalized treatments and the prediction of the response of drugs according to the genetic and phenotypic profile of each patient. A clear example is the “Human Cancer Models Initiative (HCMI),” a project that is creating a global biobank of cancer organoids. However, there are some challenges: high costs and complex technology [17].

Modeling of diseases

Organoids appear as a powerful and versatile platform for studying pathological conditions such as infectious diseases, genetics and cancer.

- Infectious diseases. Organoids allow the study of the behavior of viruses and bacteria in order to better understand host-pathogen interactions and improve the specificity of antibiotics and antiviral agents. This may lead to the development of more specific antibiotics and antiviral drugs [18].

- Genetic diseases. CRISPR/Cas9 and other such technologies allow organoids to be produced with specific mutations to better investigate diseases [19].

- [Cancer]. Organoids produced from patients' tumors retain the heterogeneity of tumors, thus opening up the possibility of testing new treatments and identifying therapeutic targets [20].

A tool to find medicines more quickly and safely

Organoid models are much more effective in drug discovery and toxicity assessment compared to 2D cultures. They offer more accurate physiological responses and accelerate non-invasive testing of customized medications for each patient. In addition, they reduce the use of animals towards more ethical and sustainable research. In addition, they allow mass screenings in less time and at a lower cost [21].

[Overcoming the new limitations of personalized medicine]

Thanks to personalized medicine, the healthcare paradigm is changing; using the individual data of each patient, it is possible to design prevention, diagnosis and treatment strategies. In this context, the clinical application of organoid models will play a key role in allowing patient-derived organoids to predict individual drug responses.

- Transplant therapy. The development of organ models-donors will have a positive impact on regenerative medicine. For example, the organoids of the sweat glands have been used in mouse transplants, and the epidermis and the reconstitution of these glands have been achieved. However, the main challenge is the inability to create complex and vascularized structures [22].

- [Immunotherapy and gene repair]. By combining organoids and immune cells, researchers can study antitumor immune responses in order to develop new treatments. For example, co-culture with effector T cells can produce an effective anti-tumor immune response by reducing the survival of organoid tumor cells and increasing immune cell function. On the other hand, organoid cultures can also be used to repair genetic mutations. One example has been the development of retinal organoids, which has opened a pathway for future genetic therapies to treat vision loss [23].

Are organoids, therefore, the new allies of the future of medicine?

Organoids are not only a major scientific breakthrough, but also a unique opportunity to understand health and disease. Its versatility, its ability to mimic human tissues more accurately than traditional cell cultures and its ability to customize diagnoses and treatments open up a promising future in medicine. There are still some challenges to overcome, such as the standardization of techniques and the achievement of broad clinical applications, but it is clear that organoids have jumped beyond the curiosity of the laboratory and have become the main allies of a more precise, ethical and accessible medicine.

Imagine what it would be like to study the human brain without opening a skull. Is there the future of biomedicine?

Bibliography

- Clevers, H. 2016. modeling Development and Disease with Organoids. Cell 165, 1586–1597.

- Zhao, Z., Chen, X., Dowbaj, A.M. et al. 2022. "Organoids." Nat Rev Methods Primers 2, 94.

- Gómez-Álvarez, M. et al. 2023. addressing Key Questions in Organoid Models: Who, Where, How, and Why? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(21), 16014.

- Thomson, J.A. et al. 1998. embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science 282, 1145–1147.

- Takahashi, K., Yamanaka, S. 2006. “Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors”. Cell 126, 663–676.

- Wang, Y. et al. 2022. “Modeling Human Telencephalic Development and Autism-Associated SHANK3 Deficiency Using Organoids Generated from Single Neural Rosettes”. Nat. Commun 13, 5688.

- Ho, T.C. et al. 2022. “Hydrogels: Properties and Applications in Biomedicine”. Molecules, 27, 2902.

- Sun, J. et al. 2017. “Controlled Release of BMP-2 from a Collagen-Mimetic Peptide-Modified Silk Fibroin– Nanohydroxyapatite Scaffold for Bone Regeneration”. J. Mater. Mater. Chem B, 5, 8770–8779.

- Ning, L. et al. 2015. “Porous Collagen-Hydroxyapatite Scaffolds with Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Bone Regeneration”. J. Oral Implantol 41, 45–49.

- Goonoo, N. & Bhaw-Luximon, A. 2019. “Mimicking growth factors: role of small molecule scaffold additives in promoting tissue regeneration and repair”. RSC Adv. 9, 18124–18146.

- Siller, R. et al. 2015. “Small-molecular-driven hepatocyte differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells”. Stem Cell Rep 4, 939–952

- Takasato, M. et al. 2015. “Kidney organoids from human iPS cells contain multiple lineages and model human nephrogenesis.” Nature 526, 564–568.

- Wang, Q. et al. 2015. “Non-genetic engineering of cells for drug delivery and cell-based therapy”. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 91, 125–140.

- Davoudi, Z. et al. 2021. “Gut organoid as a new platform to study alginate and chitosan mediated PLGA nanoparticles for drug delivery”. Mar Drugs 19, 282.

- Dalby, M. J., Gadegaard, N. & Oreffo, R. Oh. Oh. 2014. “Harnessing nanotopography and integrin–matrix interactions to influence stem cell fate.” Nat. Mater 13, 558–569.

- Fluri, D. A. et al. 2012. “Derivation, expansion and differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells in continuous suspension cultures”. Nat. Methods 9, 509–516.

- National Cancer Institute (NCI) Human Cancer Models Initiative. Available online: https://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/hcmi.

- Ettayebi, K. et al. 2016. “Replication of Human Noroviruses in Stem Cell-Derived Human Enteroids”. Science 353, 1387–1393.

- Schutgens, F., Clevers, H. 2020. “Human Organoids: Tools for Understanding Biology and Treating Diseases”. Annu Rev. Pathol Mech Dis 15, 211–234

- 20. Vlachogiannis, G. et al. 2018. “Patient-Derived Organoids Model Treatment Response of Metastatic Gastrointestinal Cancers.” Science 359, 920–926.

- Blomme, S.A.R., Will, Y. 2016. “Toxicology Strategies for Drug Discovery Present and Future”. Chem. Res Toxicol 29, 473–504.

- Sağraç, D. et al. 2021. “Organoids in Tissue Transplantation”. Adv. Exp Med. Med. Biol 1347, 45–64.

- Singh, R.K. et al. 2015. “Derivation of Retinal Cells and Retinal Organoids from Pluripotent Stem Cells for CRISPR-Cas9 Engineering and Retinal Repair”. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis Sci 56, 3591.

- Verstegen, M.A. et al. 2025. “Clinical applications of human organoids”. Nat Med 31(2), 409-421.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian