What are our family monkeys?

Both for visitors to the zoo and for the experts anatomists, it seems evident that chimpanzees and gorillas are more united with each other than with man. They look very similar. Chimpanzees and gorillas are hairy and rest on four legs. Man, on the other hand, no. Their legs are short and their arms elongated, jump from the tree to the tree and run through the fingertips. We have long legs and short arms, very flexible hands that do not carry weight of biana. Their brain is small and the human is large; they have large beta-blockers, we are small; the back teeth have a thin layer of enamel, our thick ones.

By these and other similarities between them, the comparative anatomists were convinced for over a hundred years that two types of African monkeys were close relatives. Assuming this was so, our common ancestor, the unknown monkey, would remain enigma. Like chimpanzees and gorillas, which, like fingers or humans, was on two legs or had nothing to do with the previous ones, was it totally different?

Although anatomy seems to bring chimpanzees and gorillas closer and away from humans, scientists are collecting evidence that separates the two types of monkeys and considers man and chimpanzee as close partners. What are the reasons for this idea?

The court needs blood tests to decide the paternity of someone, it is not enough to have red hair and green eyes of the possible father. Physical similarity has often led to erroneous consequences. In the case of our ancestors, blood tests are molecular comparisons of proteins and DNA, which shows better kinship than having a similar appearance. A thick dossier shows that human molecules and chimpanzees are more like gorillas. This means that the common ancestor of humans and monkeys could resemble the chimpanzee.

Many anthropologists, however, do not share this vision. They want to keep believing that the main test to decide the origin are bones and teeth. Each anthropologist has his favorite portrait of his origin: some believe it is similar to the gorilla, others resemble the orangutan, some say it looks like the liver and others say it looks like the disappeared monkey 10 million years ago. There are those who say that we can never know how it looked.

Although the weight of the DNA sequences that drive the union between human beings and chimpanzees is growing, anthropologists react to the molecular test in the same way that people react to the evil event: first denying the event, then by rage, then by discontent and finally accepting the event by desperation.

All these stages are well represented in anthropological literature.

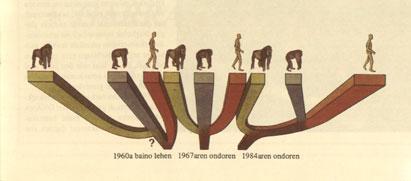

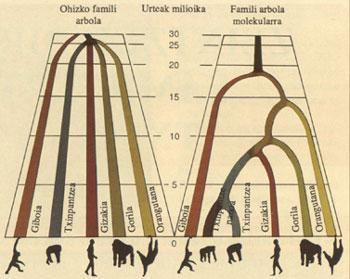

The denial phase began in the 1960s. Morris Goodman of Wayne State University (Detroit) and later Vincent Sarich and Allan Wilson of the University of California (Berkeley) claimed that human beings, chimpanzees and gorillas were intimately united and that among the three there was no other closer pair. This was demonstrated by immune tests of proteins in the blood. Sarich and Wilson concluded based on their data that the three lineages came from a common origin, about five million years ago.

This “estrangement” between man and the African monkey at that time was discarded by anthropologists from almost everyone. Anthropologists already had what they called “human origin” (Ramapithecus, 14 million years ago), which meant that 15-20 million years ago men and monkeys moved away from each other. Between morphological tests and molecular data of the fossil series there seems to be a direct contradiction. It is impossible for both to be correct.

The ancestor walking on his fingers

Sarich convinced that a fossil over 8 million years old could not be human, regardless of its appearance. The alternative, Sherwood Washburn of Berkeley pointed out, was that the common ancestor of man and African monkeys was African and on the fingers.

This attitude provoked a rage among paleoanthropologists during the 1970s. What kind of tests best established genetic kinship over time, morphology, or molecules? The writings of the 1970s are replete with attacks on molecular anthropologists, especially Sarich. This insisted that the genetic water of the union, better than the bony parts and teeth, is tested by molecules. Sarich threw out paleoanthropologists: I know my molecules have ancestors. You do not know that your fossils have offspring.

Meanwhile, the data on the molecular trend were accumulating and the story was always the same: humans, chimpanzees and gorillas were intimately united. The researchers indicated which couples were unable to approach immunology and amino acid sequence techniques. If we could know who that couple is, we could begin to define what the common ancestor was like.

In the 1980s researchers developed advanced techniques, such as rapid sequencing of DNA. At the end of this decade, most DNA analyses indicate more than the relationship between chimpanzees and gorillas than between chimpanzees and humans. Three different types of tests, DNA nuclear sequencing, mitochondrial DNA sequencing, and DNA hybridization, strongly promote the binding of this pair.

Members of Wayne State University, Morris Goodman, Michael Miyamoto, Richard Holmquist and Shintaroh Ueda of the University of Tokyo, have studied sequences of globin fragments of hominids and immunoglobulin genes, respectively. In both cases, human and chimpanzee sequences have been found, the most similar.

As Yale University's Charles Sibley and Jon Ahlquist have studied, hybrid human and chimpanzee DNA is more stable than hybrids between human and gorilla or chimpanzee and gorilla by 20%. This means that the gorilla lineage moved away from the common trunk a million years before the lineage of human beings and chimpanzees.

It seems that anthropologists, found in the last phase, have come to partially accept the implications of molecular testing. For twenty years they abandoned the Ramapithecus, considered man's ancestor.

Paleontologists now claim that Ramapithecus is the ancestor of orangutans.

Anatomy and fossil series provide a lot of information about how to live and adapt. The series of fossils and the anatomical parts reflected in them are proof of a sequence of evolutionary development. Without the series of fossils, we could not know that our ancestors moved on two legs until their brain was older or that the savannah was the first habitat of the human being. But when it comes to defining the lineages of development, we cannot trust the series of anatomy and fossils. However, paleontologists maintain this vision.

They gathered around the methodology called cladistic. Here, the genealogical trees of the fossils of primates and living primates are constructed from their “primitive” and “derived” characteristics (especially of teeth and bones). The subjective element we have in this way of building genealogical trees is summarized in the phrase: they did not even agree on a single family tree.

The main virtue of molecular data is that they are objectively detailed and comparable in different laboratories. This technique does not allow to adopt and select the “characteristics” of a particular dismemberment model. Morphology, for its part, reflects the adaptation and origin of both, and based exclusively on anatomy, there is no possible release of both elements.

It is possible, of course, that there is no real opposition between morphology and molecules, since the molecular structure is the basis of the anatomy of all living organisms.

Since the genetic material that determines development, anatomy, physiology and behavior is DNA, the most basic message about developmental relationships must be the same. DNA sequences do not tell us (at least yet) how an animal or plant lives. This information refers to comparative anatomy sawdust, field study and (in the case of missing species) fossils.

The path of evolution

As often happens, when respectable experts disagree with evolutionary relationships between living organisms, molecular data can help establish arguments. The apparent contradiction between molecular data (equating chimpanzees and humans) and morphological data (equating chimpanzees and gorillas) helps us choose between the possible paths of evolution.

Chimpanzees and gorillas can resemble each other by their close kinship, by the persistence in one and the other of the qualities lost in human ancestors or by the existence of similar cohabitations from different forms of life. Molecular data drives the second option. The first option was to leave out and chimpanzees and gorillas have not internalized independently the similarities with safe walking on fingertips, fine tooth enamel, body hair, small brains and other similarities. It is safer to think that humans have lost these characteristics in their development.

Walking on four legs and having a thin layer of enamel have been mentioned as one of the characteristics that has most joined the chimpanzee and the gorilla against humans; humans walk on two legs and have a thick layer of enamel. Orangutans also have a thick layer of enamel, do not move on the fingers, and all molecular studies have shown that the distance from humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas is twice that of these three.

Chimpanzees and gorillas, walking on the fingertips, work well on the ground and are able to climb into the trees and swing between the trees. If the chimpanzee, gorilla and common ancestor of humans circulated on the fingertips, starting to walk on two legs in the African savannah was a relatively small but important step for early humans. In this savannah the trees are more scattered than in the jungle.

According to some anthropologists, the common ancestor was not the one that circulated on the fingertips, but the one who lived on the trees like most monkeys. From this point of view, the ancestor descended from the trees and provoked two lineages: the lineage of chimpanzee gorillas (which came to walk on the fingertips) and the lineage of hominids (which came to walk on two legs). The promoters of this vision claimed that the anatomy of the hands of living beings and human fossils never give evidence of what has been on the fingers.

Walking on two legs caused profound changes in the organization of human anatomy: the shorter upper limbs, the longer and heavier lower limbs and the fixed stable feet that support the entire body weight. Consequently, in the development of hominids the hands of humans stopped bearing weight very early. The footprints of hominids of 3.5 million years ago discovered in Laetoli, Tanzania, have no trace that would pass over the fingertips.

Anthropologists working at Swartkrans in South Africa have discovered the thumb bones of two million years and to a large extent our bones are equal. Together with these bones they have found tools made of stone or bone, from the same time. No evidence can be expected that the hand that can handle such tools is on the fingertips.

The Australopithecus of the first epoch looked very much like chimpanzees. Lucy, the specimen of Ethiopia of three million years, has been called a two-legged chimpanzee. It has a height of one meter, a chimpanzee-sized brain and a proportion of its upper and lower limbs between chimpanzees and humans.

According to new studies by Tim Bromage and Chris Dean at the University of London, Australopithecus teeth come out and grow like chimpanzees.

All these findings indicate that chimpanzee and the common anchor of humans is similar to chimpanzee and that in the last 5 million years the lineage of chimpanzees has changed much less than that of humans. Many anthropologists do not admit that chimpanzees, or any other living monkey, resemble the common ancestor. Those who believe that we will never know what this ancestor was like prefer to build their own mosaic from fragments and fragments of different living monkeys. Others believe we have to wait for more fossils.

Fossils are always welcome, but unfortunately the name of the common ancestor is not engraved on pieces of bone and teeth. In the last century, the discovery of each new hominid has been considered by the researcher as a potential human ancestor.

There is already a case of molecular, anatomical, behavioral and fossil tests for the ancestor as a chimpanzee. Jane Goodall's films about chimpanzee behavior in the jungle indicate that chimpanzee behavior is largely human in social interactions, communication, and tool management.

The existence of two different species of chimpanzees is often ignored: the common chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes, and the rarest pygmy chimpanzee, Pan paniscus. Pygmy chimpanzees and common chimpanzees are quite different. The first of them has smaller betagins and usually moves on two legs. Pygmy chimpanzees are less aggressive, distribute their food much more than the previous ones and live in larger groups. Pygmy chimpanzees expand the concept of “chimpanzee” and to some extent may be more like normal chimpanzees and human anchor.

The unknown monkey, our common ancestor, is not, of course, like any kind of monkey, but the paleontological, attitudinal, anatomical and molecular borders push us towards a creature like chimpanzees. According to molecules, this ancestor is more related to living chimpanzees than gorillas. It surely looks more like the chimpanzee than any other monkey. Knowing that chimpanzees can circulate on two legs and that they are social beings who can use tools, also indicates that humans can come from the same ancestors that come. The first fossils known about humans were similar to those of chimpanzees in the structure and size of the bones, and especially distinct in teeth and pelvis.

Our current portrait of Arbaso is similar to that of the police to detect someone who has barely seen many witnesses. It is not an exact portrait and the big and small details may be wrong, but it gives us the basis to know them until more information is obtained.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian