Smart drugs, brain incentives

Four years ago a survey conducted by the scientific journal Nature had quite an impact. The online survey was open and the objective was to know if participants consumed substances to improve brain activity, that is, if they received smart drug.

Specifically, they asked about the use of three drugs: methylphenidate (Ritalin), used to treat inattention and hyperactivity; modafinilla (Provigil), sleep disturbances, fatigue and jet lag syndrome; and beta-blockers, common in treatments against arrhythmia and anxiety.

The response was 1,427 people from 60 countries, and one in five recognized that they used them to treat not health problems but to improve care, concentration or memory. Although in previous surveys it was explained that the most common consumers were students between 18 and 25 years old, in Nature no significant differences were observed by age.

Of the three drugs, the most common was methylphenidate, which was absorbed by 62% of those taking the incentives, 44% modafinil and 15% beta blocker, such as propanol.

In addition, it was indicated that they were fed other substances such as amphetamines, anti-Alzheimer drugs such as meclofenoxate, grandson of wheat and omega-3 fatty acids.

There were people who used every day, every week, every month, or occasionally, and half of them reported having side effects: headache, anxiety, and sleeping difficulties. But side effects were not related to the frequency of incentives. On the other hand, almost half obtained these substances from the doctor, one third online and the rest in pharmacies.

It should be noted that most participants (79%) viewed with good eyes the use of these drugs for this purpose. However, they felt that they should be limited to children under 16, although a third responded that they would be pushed to give their children if they were received by the rest of the school children. It became clear, therefore, that although the use of brain incentives was acceptable for the majority, in some cases the issue raises doubts.

From the street to the laboratory

Last year two media outlets conducted a similar survey: BBC Newsnight sessions and science journals New Scientist.

761 people responded, and more than a third responded that they had ever received some kind of incentive. Of these, 40% acquired them through the Internet and almost all (92%) declared their intention to recover them.

The New Scientist himself acknowledged that the survey was answered by an insufficient number of people representing society, but that useful conclusions could be drawn. Among them, he highlighted the modafinilla, methylphenidate and an amphetamine used to treat inattention, which is sold with the name of Adderall, which are the most used, that is, those mentioned in the questionnaire of Nature approximately.

For New Scientist, the difference between experiences is "striking". For some, the experience was very beneficial; for example, "it helps me concentrate; I can spend six hours studying a topic that would bore me in two hours," said one. Another, "doesn't help me at all, it makes me feel nervous and distressed, and in 15 hours I can't sit down."

At the Newsnight session, a student at the University of Oxford had his experience with the modafinilla: "I've taken it a few times, especially because it helps me to be awake and keeps me focused and alert for a long time. I don't take it many times, but I find it very useful if I have to be between 20 and 30 hours working."

The extensive information available on the Internet also corroborates the above in both surveys: medicines used to treat certain health problems have a different use and receive healthy people, especially to stay awake and focused for a long time.

However, researcher César Venero has warned that "there are no kits on the market with nootropic effect, that is, substances that have a specific function of improving brain activity".

In fact, Venero researches this type of substances and published in February an article on this topic in the scientific journal PLos Biology.

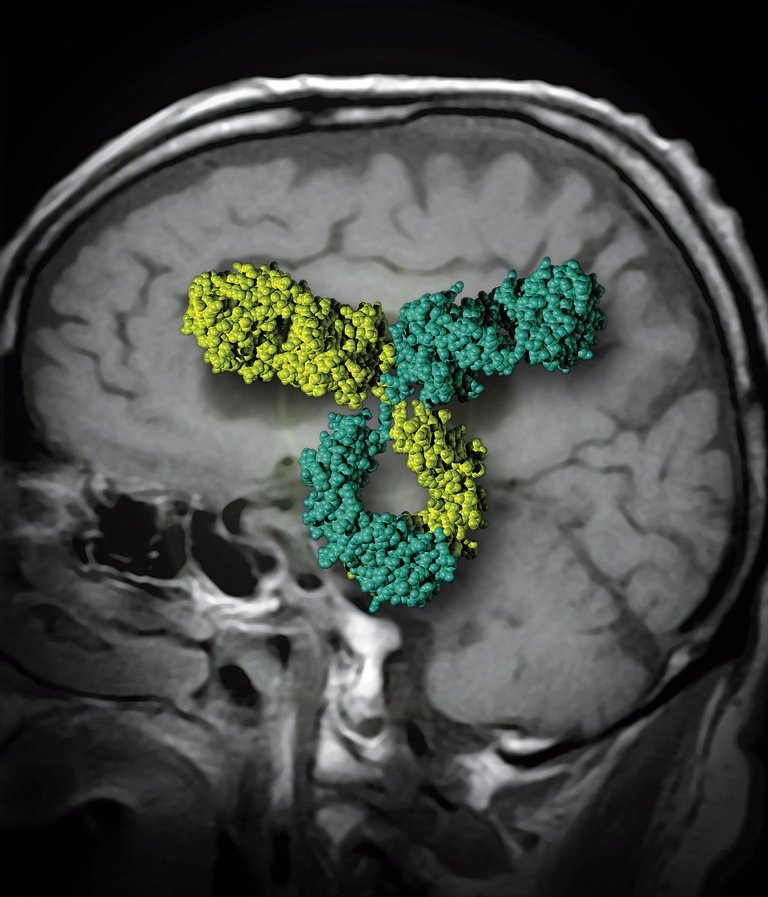

Venero said that "there are drugs to stop cognitive loss associated with Alzheimer's and this type of pathologies. Many of these drugs have a similar mechanism of action, which generally prevents neurotransmitter glutamate from being associated with one of their receptors, NMDA. In fact, glutamate is very important for normal cognitive function, but if overreleased it can cause cognitive loss and neurons." However, for healthy people who want to improve memory and the ability to learn, Venero has announced that these drugs can be "harmful".

However, "if a substance with these effects is found, which has no side effects, it would be possible to improve the cognitive functions of many people," says Vero. In fact, together with his teammates he investigates a synthetic peptide, the FGL peptide, which is currently having hopeful results.

"This peptide is similar to a part of the NCAM molecule we have in the brain and is also the receptor 1 agonist of the FGF fibroblast growth factor," he explains. In animal research we have shown that this peptide, the FGL, improves the learning and memory skills of young rats. That, given that young rats have a great learning facility."

They have also taken another step: "In addition, we have found a molecular mechanism that explains the influence of FGL, which for us represents a breakthrough and opens the door to the search for new drugs. In short, other European groups will start a first preliminary investigation with people to see if the FGL has a nootropic effect also on people."

In any case, Vero wants to make it clear that, like any other medicine, the use of nootropics should be regulated and that before its administration, a professional should decide if it is necessary to give them and check the benefits and harms that could be caused to order them only when necessary. Zuhur adds another detail: "People with good cognitive function are very likely not to use nootropic drugs, but we must wait for the results of the first clinical and epidemiological studies to know if any of the nootropic drugs being developed will now serve to improve the cognitive abilities of all of us."

Ethical issue

Even before brain incentives come to market from laboratories, experts discuss the ethical issue of using these substances. For example, along with the questionnaire, Nature published an op-ed: Towards responsible use of cognitive-enhancing drugs by the healthy, i.e.: "Towards responsible use of drugs that improve cognitive functions in healthy people." The article is the result of a seminar held at Rockefeller University, involving lawyers, psychiatrists, ethics experts, public health officials and brain researchers.

If the title of the article is significant, the underlying phrase is even more representative: "Society must respond to the growing demand for brain incentives. This answer must begin by ruling out that it is a bad word of incentive."

After mentioning which medicines are used to improve brain activity, they are compared to other methods that are traditionally used, such as teaching, reading, sport, nutrition and sleep. And their conclusion is that, in principle, adults with good minds should have a "chance" to use drugs to improve their cognitive abilities.

In the meantime, they also give arguments contrary to the arguments used to rule out this type of medication, but they recognize that they generate ethical doubts in three aspects: security, freedom and correction.

In the case of safety, the authors of the article call for "evidence-based" measurement of the benefits and harms of brain incentives. They also ask that children be especially cared for. And children are precisely the ones who worry the most about the next issue, freedom. They also care about adults, which is reflected in some of the problems that have already occurred - specifically, they quote the military, who have long been given amphetamine and modafinilla to be alert. But the case of children seems extraordinary to them and they believe that their rules must strictly protect the well-being and health of children.

Finally, they analyze the issue of correction. In his opinion, even without taking into account brain incentives, there are already injustices such as differences in teaching. However, they are aware that the use of these drugs carries the risk of increasing socio-economic differences. Therefore, the rules should also serve to avoid it.

Finally, the article concludes with the following: "As with other technologies, it is also imperative to think and work hard to make the benefits the greatest possible and the minimum damages."

Although this article is from 2008, in many other later articles that have been published around the subject, experts show similar opinions. However, it seems that the opinion of street people is not so unified. This is demonstrated by at least the results of the Play Decide sessions.

Play Decide is a methodology that helps make decisions and reach consensus on the issues that generate debate. Based on team play, the game about brain incentives was created in 2010. At the moment, sessions have been held in the United States and six European countries, and they are not enough to consider the results as representative, but they can give an idea of what people think.

Thus, the results indicate that morally for most it is not admissible to use incentives to improve normal activity, but only accept therapeutic use. And if you use it, it should always be by medical prescription. However, usage surveys have shown that it also uses healthy people on its own. The debate is on the street.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian