“Memory is female.”

under the title “Building memory, unearthing the past”, the archaeologist Lourdes Herrasti Erlogorri and Ana Galarraga Aiestarán had a talk as part of the cycle “In the light of women scientists”. They talked about their career in Aranzadi, archaeological studies and the human aspect behind them. In fact, Herrasti has participated in important archaeological discoveries and, in recent years, is mainly involved in the exhumation of the deposits of the Spanish Civil War. In these pages, the most significant excerpts from that conversation have been recorded in writing.

I studied Geography and History in Vitoria-Gasteiz and, while studying there, my teacher Amelia Baldeón asked me if I wanted to go to an excavation in Gipuzkoa that summer. I said yes; we came to Jesus the Most High, and then my exchange with Aranzadi began. Since then, I've been in Aranzadi.

In fact, I was in the Lane, just where the bone of the first domesticated dog appeared in Europe.

Yes, I started in the Paleolithic, and I ended up in the contemporary era, studying the Civil War pits. In Ordua, I've done the whole chronological route.

No, I don't. Archaeology has a method that can be applied in the same way to ancient and contemporary sites. The method is valid anywhere and for any time.

The course of man, how man lived his time. Or how he died; I'm more interested in knowing that.

That's the way it is. And now, in the graves of the Civil War, we don't find clothes, but the objects around them give us terrible information about the graves. What customs they had; whether they were smokers; whether they believed it or not, because they wore a medal, for example...

When we are excavating a Hobi, we have relatives around us. In a Paleolithic excavation you don’t have it: you are, taking the land and studying it, but you don’t have any feelings. On the other hand, the fact that you have relatives next to you gives you a new value and, in addition, you experience other sensations. It’s completely different, and the relationships are also different. You don’t have a bone in front of you, but a person’s skeleton and, next to it, their descendants.

We can't complain here. since 2002 we have had an agreement with the Basque Government and, currently, we carry out all the necessary tasks with the Evento Institute. This is also the case in Navarre, where since 2015 we have had an agreement with the Navarre Institute of Memory and we have their support and support for everything we do.

On the other hand, in the rest of the state, there is everything.

That's what it is. It’s a real team; we all work together. There are sedimentologists, specialists in Prehistory, biologists... there are people with different types of training.

And, as we said before, we investigate death. Here we have the oldest skeleton of the Basque Country. We found it in Jaizkibel, a cave, and it is undoubtedly the oldest known. And I was in that position [in the fetal position].

We began to study the caves. In the Paleolithic and especially later in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, the bodies were buried. The skeletons are exposed, and around them, pendants, for example, beads of necklaces. Or spikes and other weapons that you would need in your next life. This was what the archaeologists were working on in particular, but Paco [Etxeberria] and I studied the bones. We know what diseases they are suffering from. We also know the age, more or less.

Above all, we extract bones from necropoles or churches. They date back to the Middle Ages, where the skeletons appear, usually intact. The tombs may be made of stone, wood or other materials. And when we analyze it, we see that, on one hand, his ribs were broken, on the other hand, he had osteoarthritis, very developed, which obviously caused him pain... We also checked their teeth, and that’s how we know what their diet was, whether they were soft or hard.

That's what it is. To pull, for example, to work on leather or laces... And they also used chopsticks to clean the intervals of the molars or teeth. They have also found these in Atapuerca; it seems very common.

And when we look at everything, we get the demographic profile. That is, the number of children, the number of men, the number of women, and the distribution by age and sex are made. This shows what kind of society it was. For example, it is normal for women to die sooner [than men]. Many women died in childbirth.

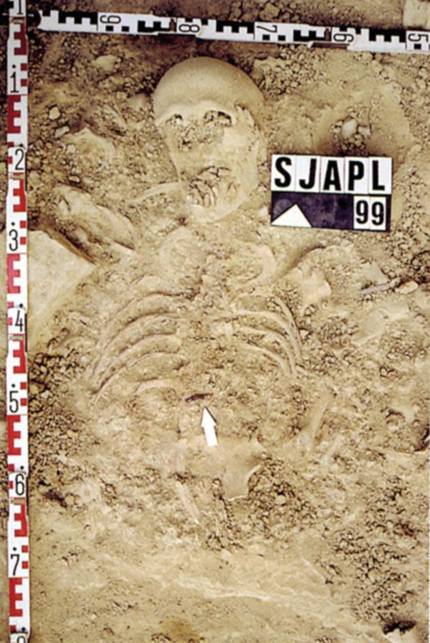

San Juan Ante Portam Latinam is a gem. we met in 1990; I was pregnant. My daughter was born in June, and a month and a half later, I was excavating. I'd breastfeed him and go to the excavation again.

Here we found, under a rock shelter, the bones of 323 people. All at once. That means they were buried at the same time. That's not normal. It means something bad happened. It can be a disease, a massacre, or a conflict between them.

It looks like you have an arrow between your ribs. Others have fireworks in them. One of them has the point of fire embedded in his spine; that's how he was killed. He destroyed his spinal cord, so he died at that very moment. Others remained alive with the arrowhead inside. That's kind of weird. One has it on his arm, inserted between the cubit and the radius. The other one, on the neck.

It is clear that they had great conflicts, that there was great violence, and that they fought against each other. That's why they're all buried together. There are more than three hundred of them, and one hundred of them, children under five years of age. It really was a special place.

If they had a head injury, doctors or pseudo-doctors performed interventions: they pierced the scalp. Even if they were supposed to die, they did not die; they were still alive. There is a case in Álava that has a hole of 5x5 cm and survived.

It is necessary to acquire the bones, to wash them well, to prepare them well, and then to reconstitute them in order to understand them. We have to solve the puzzle.

We study not only the bones, but also the mummies. And the mummies where, in Egypt? No, we have mummies around us, too.

In fact, this one is from Arrasate. They called him Amandre Santa Inés. My late father told me that when he was little there was a mummy of an animal in the church of St. John. And we went to the church to ask, and the priest told us that he wasn't, that he wasn't. But then he asked better, and they had the mummy hidden under the stairs. And it is Inés Ruiz de Otalora, a very important character, because her husband was Mr. Okariz, Secretary Felipe II.aren. They brought them both. Inés was brought in mummified because he was first buried in Valladolid.

The way people saw that this woman didn't rot, they thought it was magical. They created some copla, a litany: “Amandre Santa Inés/ Bart inddot dream/ If it is good for bixon part/ If it is bad for nowhere in part.” It is currently on display in the church of San Juan.

They are very impressionable, very, very emocial things. Then there comes a time when you need to harden yourself. You have to set a distance, otherwise the feelings overflow and eat you up.

For the DNA test, it is not enough to have bones. We need someone from the family to compare the samples. If we don't have a family, we can't identify it. And here [the Falkland Islands] we have managed to identify all but two. Now, the war veterans, the survivors, are helping in the excavations, in the form of therapy, because they had a very bad time. Most of them have not overcome it, they feel abandoned, sold, and they are doing archaeological excavations to somehow recover that memory. Archaeology has great value.

in 2000 we went to Leon by chance. They called us. They were going to do a exhumation, and they asked us if we wanted to go, and we went there. We could not imagine at all what we would find and, even less, everything that he brought afterwards. We went to work in a ditch, but we didn’t know that the Civil War had caused so many deaths. So many people illegally killed. Because they're murders.

it's at least 111,000; Garzon got the names of 111,000 people. It is estimated that there may be up to 130,000. Most of them were killed in Tiroz and clandestinely lost underground. Lost in memory and hidden from society as a whole. They've been underground, silently, because there's been panic. We break that silence and unearth them. And most of the time women come to us [to give information about the pits] because the memory is female. "Memory" is said in Spanish in the feminine, and so it is, because memory is in the hands of women. They preserve the memory of the family: family photos, family stories...

Starting with a photo of a young woman who told them where her father's grave was, she has revealed several significant exhumations until the time for the colloquium has run out. Hard stories, full of cruelty and humanity. And thanks to each exhumation, how they have broken the silence, how they have regained their memory.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian