"It is surprising how much research has been done on sound and little listening"

--> Listen to 5 sounds, 5 listening ways:

A priori, for me there are no differences, and the accepted are totally subjective. The most interesting of this distribution is the attempt or need for differentiation that hides behind. For our previous generations, the music we heard has always been a noise, and for us it will also be what our next generation will hear. This means the ability of music to strengthen or build your identity. In this distinction there is a count of values. As a young child, the music our parents listen to can be a horterada and then, over time, you find yourself listening to boleros. And for parents it is usually similar: listening, understanding, learning...

Yes [with total security]. For that is one of the opponents we carry with us: we believe that we are able to judge music by its aesthetic values and it is not so; we, in reality, do not know, learn.

We believe that music is chosen by us, because it comes well with our nature, etc., but music really chooses us, because that music is a break with our predecessors. Therefore, when we choose the music, we embrace it to reinforce and performer that break.

When defining sound, noise and music, sound is the common denominator of the three, which admits in its interior all kinds of vibrations: taste and not taste, that strengthen us or not personality... Music would be a human expression of sound; a somehow response to everything we hear; and that means a response in society, in cultural status, to the system...

And it would be noise, if necessary... [has interrupted the dialogue] a politicized sound. Politicized in a sense: noise always implies rejection. It is negative, it is always the other. And if it's of self, it will be in the context of music, where that break forces you to adopt an attitude and say "I make noise against this". The noise is always against something, the noise always has...

Yes, the other is very present. Without more, there would be no noise, that is the key. The noise, and within this music, is an adjective that we use to describe the sound of the other, which we politicize remarkably. We politicize to establish scales in our relationships with others, such as social ones. We use abstract and totally subjective concepts such as noise and silence to describe the different social levels.

The foreigner is always noisy; the neighbors are always noisy; the rich are always silent and the poor, increasingly poor, more noisy. That also has to do with music... For example, take the topic: Gypsies are very noisy. Why? Because they are always playing music. And where do the music play? In the street. But if you put that same music into the Kursaal, then it's no longer noise. Here is the X-ray of our values, which is for me the most interesting in this world of hearing.

And precisely our education departs from that division and already in the ikastola they teach us what is music, what is noise, but they do not teach us what is sound. Why? Because the educational system, somehow, needs those divisions. A teacher needs that scale to develop with his students: his voice is not noise and what others do is noise. And we accept that authority, but on the other hand, who has not provoked scandal, despite the silence of the teacher? Somehow, we all practice noise at some point. It is necessary that these years of education are important to reinforce these values, but no one gives us a broad spectrum of this phenomenon. And that can be criticized, but it is not at all denounceable; in short, our society is based on those values.

The Map of Sounds was created here, in Arteleku. So far we have received the help of Arteleku to have the web, but now we want to start a new path, giving autonomy to the project, because we are convinced that it has to be a collective project. An obvious problem is the impulse. Although it has a lot of visits, many participants, have been running for eight years, it costs to convince any public organization. We believe that there is something that does not come at all, and that in the end it is always the idea of heritage that prevails.

We are very interested in this heritage issue, but it is not our main objective to form a heritage. If the objective were that, we should do a serious research, with specific resources, prioritizing sounds according to the heritage criteria. And if necessary, what interests us most is to reflect with sound recordings this change of value between the noise and the sound we mentioned before. And see how historical changes are reflected also in these sound recordings.

For example, the NODOS of Francoism have narration and music, and if you miss the sound or the image, they suddenly acquire a totally different sense. What if we heard the real sounds of those images? How would our historical accounts change?

Thus we begin to hang the sounds in the Sonoro Map to provoke a wide debate... We want to see what can come out of this debate. Over time, it has become a map of auditions. Why? We are also aware of how subjective we are when capturing and selecting sounds.

In addition, the map is, by definition, somewhat obsolete, not just the Sonoro Map, any map. With the sound, more. The sounds do not exist without movement, they are presence. People speak to us on several occasions: "You should go to that place, there is a certain sound...", but by the time we go it is no longer. We, in fact, are doing something that doesn't make much sense. By hanging a recording, you're putting on the map something that no longer exists. You are putting a sound of a time and a space in a place without time or space. The most interesting thing is that it serves to bring to light all our contradictions as listeners.

Today there will be about 1,500 sounds. With them, for example, you can do an analysis of carnivals through sounds, traffic or underwater sounds... But we are not biologists, nor anthropologists, nor anything. For us, what we hear has value from the sensitivity of art.

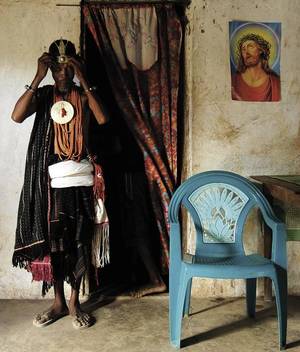

However, there are media and educational centers that use the sounds we have collected and we would like them to be used more. In fact, the Sonoro Map is free and has that function. We do not know how long we will last, but for now we have created an association, Audiolab, to manage and promote research. For the queen, analyzing the possible lines of research, we have seen that there are many ways to listen. From there have come the two new sections of the Sonoro Map: Listening writings [chronicles written before drawing close to sound recording devices, ancient noise laws…] and sound images [images representing sound]. Why can sounds not be reflected in texts and images? And in that reflection, what kind of symbologies are generated? And what importance do they have? And to what extent are we able to interpret these symbologies?

In these cases we speak of public, not sound. In fact, it is surprising how much research has been done on sound and little listening. Only the practice of music, orality, bertsolarism has been analysed... But the listener, the subject who gives value to all this, is hidden. No one has worried about hearing.

The truth is that I don't care too much. To say that music is universal is like saying that water is universal, or the word... The word and music always go hand in hand; where there is the word, there is music. Always. For two reasons: one, because music is a response to the environment, that is, depending on the environment, the music will be like this; and two, because most of the music are instruments in its creation.

Proof of this musical functionality is that all the thinkers of history have considered music. Because it serves to free music, but especially to manipulate it. If you're traveling to an unindustrialized country, you'll soon realize that music and work go hand in hand: here, for example, when women were whitening the corn, they needed timing, rhythm; in the rice fields of Vietnam, when picking up the rice, everyone has to go at the same pace... For this purpose, singing, music is used. There are also the military marches. They serve to synchronize the army. And once synchronized, what else can we do? That is the question. I am more interested than if the music is universal for what it is used.

Ethnomusicology has carried out numerous studies in this regard, although most of them have been conducted from the Western perspective. This has not only happened with music, of course, but in music it is very evident that the researcher returns what was heard on the chromatic scale. And in this process of adapting to our standards, a huge wealth is lost.

So it is. In fact, I went to search for languages. We learned that there a lot of languages were spoken and we went to record. And there we find something else: we realized that there were no sound, linguistic, or other records. Neither music. They did not even have instruments. How was it possible? Because that territory suffered a wild genocide and lost a whole generation. And with it, much of its cultural wealth disappeared.

Aware of the situation, we decided to do what we could, taking our micros and we started recording. Yes, we were clear that whenever we recorded something, we would leave a copy on the local radio, on the file or on everything. We do not know if they have done something later, but we are clear that this is theirs. It serves us as a research topic, but I have serious ethical problems to put a copyright on it. Such a situation places you before all your contradictions. What happens is that if you want to publish here an album, without wanting, you have to put a copyright, but you realize that the money that that can give will never be returned. It is another reality and serves to criticize yourself.

The only set of recordings made in East Timor is ours. That worries me a lot because we do not know what we are losing. And on the other hand it is fascinating because you find things that you did not expect at all. For example, for me it was amazing to meet Lian Nain. Think about it: in my mind I was listening and, suddenly, I found the figure of listening to its function.

Lian Naine has that responsibility: listen to everything that happens around her, what the neighbors say and think, the song of the birds, the noise of the wind, the sound of the river, what the spirits and the gods say... They listen to everything and keep it in memory. And when someone has any problem, or when a confrontation occurs between them, they turn to him and it is then when he begins to bring everything heard to his mouth. And in the end always comes the sentence or the answer. To get to this you never know how long it will take, it can be minutes or hours, but always answer the question. Moreover, its function is to listen and memorize what was heard, as if it were a human recorder.

Perhaps, to some extent, the function of bertsolari was similar in an era: it was not so much singing, but making a chronicle of an era in which memory was not written and kept. And for this I had to hear. The troubadors also did, but when writing arose they disappeared. However, bertsolaris have survived. Why? Surely because they did not fully agree with what was written. Therefore, bertsolarism can be a survival strategy, like that of Lian Nainena, to survive.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian