Letters of exile with fission

Those Christmas holidays were very special. Otto visited his aunt in the Swedish village of Kungälv. The next morning I was eager to talk about a new experiment. But he found him in a letter and did not listen to him.

Otto also had to read the letter. At first he did not believe what that letter said, but if what was told there had explanations, they could be before one of the great discoveries of history.

It was impossible to get bombing and barium with neutrons. If it was never possible to separate from an atom anything larger than protons and alpha particles, how then did the barium of the uranus? "There will be some error," he suggests to his aunt Otto. "No, Hahn is a chemist too good for it," he said. His aunt knew Hahn well; they worked for 30 years until in 1938 he had to flee from Berlin to Sweden.

In 1907 Lise Meitner met Otto Hanh when he went to Berlin to study with Max Planck. Meitner, came from Vienna. Because of the limitations women had to study, until 1901, when he was 23, he could not enter the University of Vienna. And until then he studied thanks to his parents, who considered that their children had to be given the same education because they paid for private studies.

She was the second woman to obtain a doctorate in physics at the University of Vienna. He jumped the offer to work in a gas lamp factory and went to Berlin to take theoretical physics lessons from Max Planck. There he began working with chemist Otto Hahn.

At first, when no woman was admitted to the Chemistry Institute, Meitner had to work in the basement in a room with separate entrance. Then, in 1912, Meitner and Hahn moved to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. There, for a year, Meitner had to work unpaid as Hahn's "guest". The following year he obtained his first real place in this institute. In 1917 he began directing the institute's physics department and in 1926 he held the post of professor of physics at the University of Berlin. She was the first woman to get that post.

James Chadwick would say that Meitner and Hahn would be "one of the most fruitful collaborations in the history of science." Hanh was a great chemist, methodical and precise, an absolute experimentalist, weaker in the theoretical field, while Meitner was a clear theoretical physicist, without experience in chemistry, but very skilled in the explanation of the laboratory.

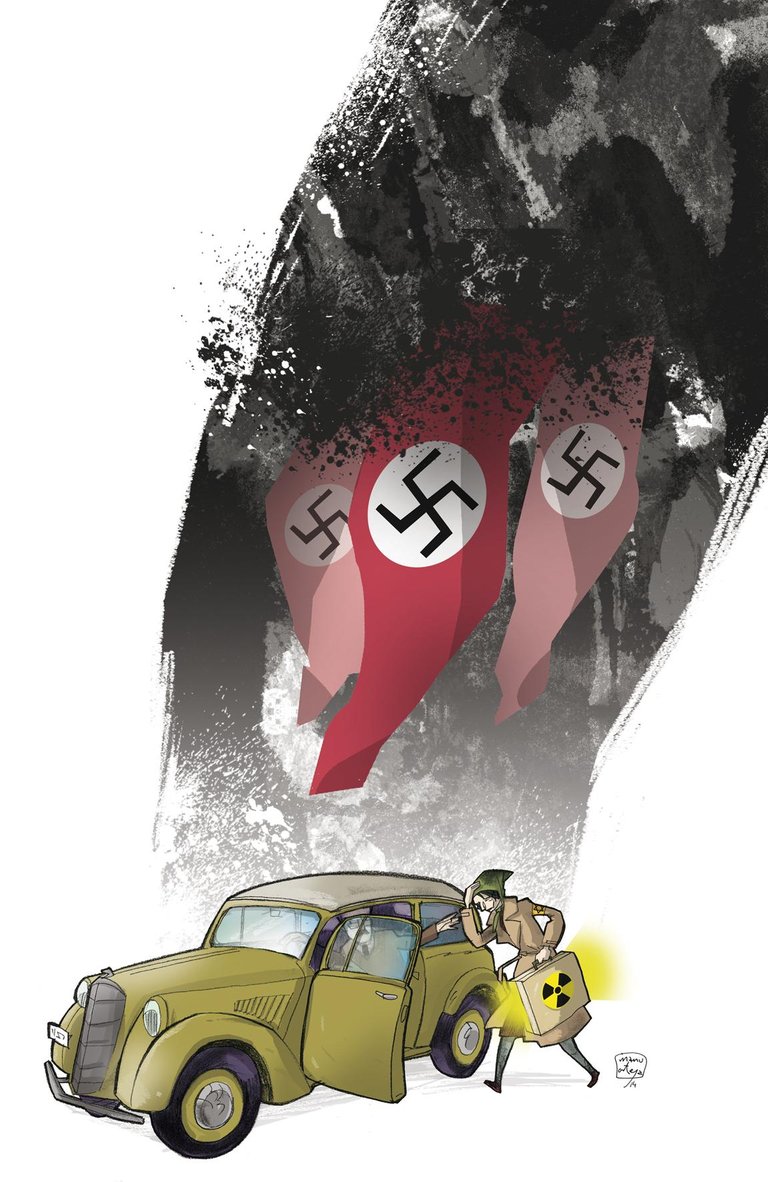

They worked mainly with radioactivity and discovered new isotopes. But when they were on the road to the greatest discovery, Germany conquered Austria and Meitner lost the support that until then provided him to be Austrian. Of Jewish origin, his conversion in Protestant in 1908 would serve him little. He barely managed to escape thanks to the help of scientists from outside and inside Reich. He left Germany forever with only 10 marks in his portfolio. It also had a diamond ring, provided by Hahn, in order to buy border guards.

He went to Holland and finished in Sweden, at the Manne Siegbanh's laboratory. He continued his relationship with Hahn by letter.

Before leaving Germany, Meitner, Hahn and Fritz Strassmann investigated substances produced by bombardment of uranium with neutrons. They were not the only ones, as were Rutherford in England, Joliot and Curie in France, and Fermi in Italy. Since Chadwick discovered the neutron, they suspected that uranium, the heavier element they knew then, bombed with neutrons, could be possible to get heavier elements.

Meitner was aware that something rare happened in those experiments. And then the newcomers from Paris said that the new substances that were generated seemed more agile than uranium. Hahn also saw it right away, and experiments with Fritz Strassmann suggested that radio was produced.

Meitner learned by letter. And seeing it makes no sense, he asked Hahn not to publish those incomprehensible results. Then, in November 1938, they met in Copenhagen and Meitner proposed to Hahn to do more experiments to discover what that radio really was.

So did Hahn and Strassmann. And there they found that the radio was not a barium, one of the elements that came out of uranium. It was surprising, but the results were clear. "Perhaps you are able to give a good explanation to this," Hahn wrote to Meitner.

Aunt Meitner and Otto Frisch's nephews sat on a trunk in the snow and began making calculations on pieces of paper. Taking into account Bohr’s “liquid drop” model for nuclei of atoms, they concluded that a neuter could produce the division of the “uranium drop” into two, by applying smaller drops. Frisch comes to the head the division of bacteria, so they called him "fission". Meitner also realized that in this division the mass was lost, so, as the famous formula E = mc 2 of Einstein said, energy was produced, a lot of energy. It all coincided. They already had the explanation!

Hahn and Strassmann published that barium discovery. They could not include Meitner in this article, which could be the recognition of having collaborated with an exiled Jew. But Strassmann would then make clear the importance of Meitner: "We were linked intellectually from Sweden ... was the intellectual leader of our group".

Meitner and Frisch published their exhibition in Nature. But in 1944 only Otto Hahn received the Nobel Prize for "finding the fission of heavy cores".

Meitner also concluded that the fission could provoke a chain reaction that would release enormous energy. And, of course, some soon saw their application. When asked to participate in the Manhattan project, Meitner did not hesitate: "I don't want to have anything to do with a bomb! ".

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian