But what is this entropy?

The two simple laws of thermodynamics build the foundation of discipline, but entropy always creates the greatest obstacle to understanding. Although the concept of energy is colloquially accessible, entropy has a confusing semantic charge. This text clarifies the technical meaning of both laws and provides the key to understanding entropy as a property.

For a few years now I have been working on a subject based on the discipline of Thermodynamics. I teach in a master’s degree. The students are therefore people who have obtained the title of engineer. That is, at the beginning of the course, when we review the subject of the degree equivalent to the Master's course, the concepts exposed in class should be made as intuitive as easy to understand. At least that's the way it is until we stumble upon the eternal stone. When you get to the entropy thing, it's over. Annual chaos: dark beans, multiple questions, more doubts. In the end, I stick to the usual practical way to get out of the gate. That is, focus on calculations and reduce the importance of understanding the concept.

I am aware that I should, in fact, place a large part of the burden on the possible deficits of my communication powers. I suspect, however, that the rest of the problem has to do with another factor, which is the usual way in which the foundations of Thermodynamics are explained.

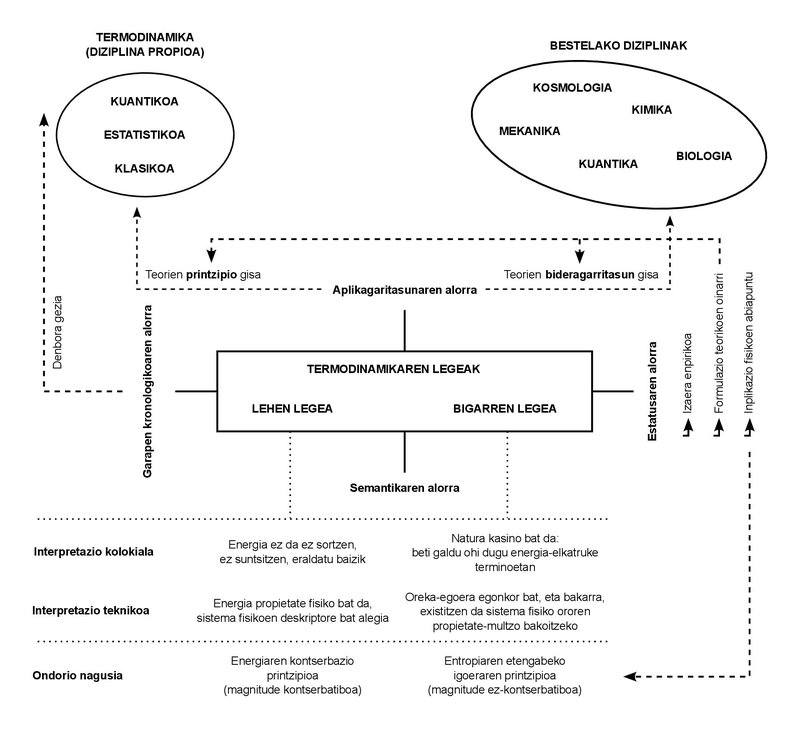

We only use two laws in the whole lesson. These laws are empirical in nature. In other words, in the 19th century in which they were formulated, they were not deduced from other principles; they were deduced directly from the cases observed in daily experimentation.

To this day, on the other hand, the incipient discipline that was then called Thermodynamics has undergone numerous developments, and the concepts that gave birth to it have been limited to the field called “Classical Thermodynamics”. These other developments have given rise to new disciplines: “Statistical thermodynamics”, “Quantum thermodynamics”, “Irreversible thermodynamics”, among others.

As can be seen from these designations, the complexity of the phenomena studied has increased, as has the formulation of theories and research. However, the proliferation of disciplines and the increasing complexity of phenomena have not succeeded in altering the basic character of the aforementioned laws. Whatever the phenomenon studied, or whatever the theory formulated, it has been affirmed so far that both laws must comply with the imposed one. Hence the importance of understanding and internalizing them.

What do these laws say? They are very easy to understand if they are expressed in simple words, and I usually explain them in class with that simplicity. The first law: energy is neither created nor destroyed, but transformed. Or using a more or less technical term: energy is conserved. Second law: Nature (indeed, in capital letters) is a casino and therefore always wins. In other words, we can interpret our relationship with Nature as a continuous exchange of energy, and in the game that this meaning entails, Nature ends up acquiring all the energy coins. Even in a third way: the amount of energy that can be useful or exploitable is constantly decreasing. And the ideal measure of this decrease is provided by another physical concept that increases in parallel: entropy.

The concept of energy is very intuitive. We use it in our daily lives and use it in situations that have different meanings or meanings. It is a concept as polysemic as it is widespread. The law of conservation of energy also has a similar status: how many times would we have heard that non-creation, that non-destruction, but the lease of transformation? What’s more, the question of conservation is also very popular in disciplines other than thermodynamics: for example, the conservation of the amount of movement and angular momentum in Mechanics, or the conservation of mass in non-relativistic systems.

the concepts of “conservation” and “energy” are therefore fully accessible to us. They have managed to make a journey from the technical language to the colloquial. It's not little. However, the notion of entropy has had more obstacles to do so. It cannot be said that it is not known, although in some way it is more mysterious than the other two mentioned. However, it is precisely with the common and shared meaning of entropy that my flask suffers the most friction. As with the students, I am aware that everyone who has come across this concept also associates it with ignorance and disorder.

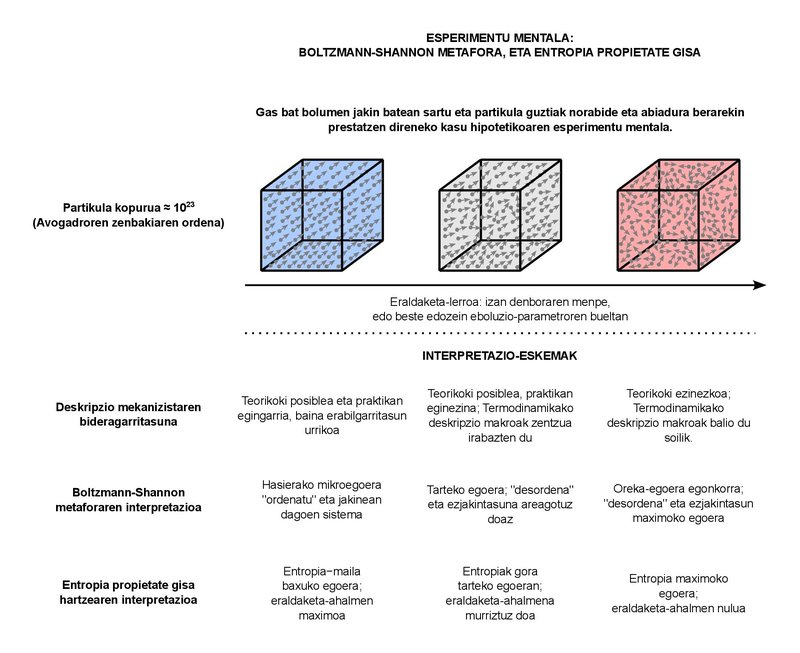

This confusing semantic charge is very understandable. In fact, the objective of classical thermodynamics is to describe the macroscopic behavior of systems formed by a large number of particles. But how many particles are “abundant”? For example, let’s say that in the typical systems that we study in the subject of “I am a teacher” we consider fluids of a few liters and a few kilograms. Whatever substance we take as a fluid, the number of particles that we can find in systems of these sizes is in the order of the Avogadro number, which is about 1023. Essentially, the Avogadro number represents the number of particles in one mole of any substance. The concept of mole can be equated in some way with that of kilogram (it quantifies the substance), but it is somewhat more basic in itself. In fact, many measurable phenomena in the physical behavior of many substances are proportional to the number of particles (and therefore to the moles), not so much to the mass. 1023 particles, on the other hand, are enough. The world population order is approaching 1010. Simply put, even if we had as many planets as there are inhabitants in the world, the population stored in all of them (1020) would be a little far from reaching the number of particles that still exist in one mole. A huge number, at least. What can we say about the macroscopic behavior of systems of this type? This is basically the question that classical Thermodynamics answers. The concepts of “pressure” or “temperature” that we use in our daily lives are part of the answer to the question posed.

It is not surprising, on the other hand, that in systems with a number of particles of this order there is a great chaos. following each of these particles, which are about 1023, is completely impossible, so we cannot give a complete mechanistic description of the system. Instead, we use the concepts of Statistical Thermodynamics, based on Statistical Physics, to combine both perspectives, macro and micro, in an appropriate way. The metaphor of the disorder around entropy should be placed there. In an attempt to justify this continuous increase in entropy that is verified in macro behavior with concepts of micro vision.

The essence of the metaphor is due to the Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann, who states, in essence, that these 1023 particles can be arranged in many ways. We can call each form of organization a “microstate”. In principle, we can imagine a macroscopic system completely defined. That is, it is in one of all possible microstates. When the system undergoes a transformation, a plurality of microstates compatible with the macroscopic approach are physically accessible. All these microstates are complementary, that is, physically possible and macroscopically indistinguishable. Since the increase in possible microstates follows the same trend as the continuous increase in entropy, Boltzmann gave his definition of entropy based on the proportionality between the two. Thus, entropy would be a macroscopic inseparability between the increasingly numerous forms of particle organization. That's the disorder.

Decades later, the engineer Claude Shannon added the concept of ignorance to the metaphor of disorder. Shannon was doing a theorization of communication systems and when he mathematically formulated the amount of information carried by messages, he came across the apparent expression of entropy, widely used in Thermodynamics. He related the increase in entropy in a system to the loss of information about it. And, together with Boltzmann’s vision, the current sense of entropy, a magnitude that expresses the degree of ignorance and disorder of physical systems, was developed.

After this short semantic trajectory, only two points. First, the colloquial meanings of the concepts expressed (energy, conservation, entropy) must be used with caution. Although they can adequately reflect the key idea of their technical equivalents, they can leave out important nuances. And the second: The same is true of the common expressions of the two laws of thermodynamics, which in some way blur the technical load they carry. In fact, energy conservation is not a formulation of the first law, but one of the consequences. In fact, the abstract meaning of the first law states that energy can be defined as a physical property. That would be its deepest meaning.

It is the same with the second law. The image of the casino may be somewhat didactic, but it is not entirely technical. Formally expressed, the second law only codifies the existence of stable states of equilibrium. The fact that every system tends to balance is an empirical fact. Well, of all the states of equilibrium, the second law states that there is only one stable state of equilibrium for each value that encompasses the set of magnitudes that describe the system. The direct consequence of the combination of both laws is that the magnitude of entropy, like energy, is a property that indicates that a system has reached its stable state of equilibrium, since in this state entropy shows the maximum value it can reach.

Energy and entropy are not so different. Both are physical properties, that is, magnitudes that can be used to describe the physical state of any system. The most basic, by the way, are those that derive most directly from both laws. And, as properties, they are properly defined for all states of the system, whether equilibrium states or out of equilibrium, stable or not. Moreover, as with the concept of energy, entropy is not a statistical or informational magnitude, although it takes its own manifestations in these fields.

As a property, energy quantifies the exchange capacities of a system, while entropy focuses on the transformation capacity. The more entropy, the less transformative power. When the steady state of equilibrium is reached, the entropy reaches its maximum value and the transformation capacity is zero. More than maximum disorder and total ignorance, we will have a perfect order and all the knowledge about the system, because we will not be able to find ourselves in a state of equilibrium other than this stable one.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian