Chimpanzee kit

East African chimpanzee observers have the theory of a strange behavior of chimpanzees and the theory mentioned seems that the distance between chimpanzee and man becomes narrower: when animals feel bad, their people can take the same plants they take to treat diseases.

According to some articles published in several scientific journals over the past decade, the psychological and pharmacological effects of chimpanzees on the consumption of certain leaves and seeds focused on the search for such seeds and leaves. Despite no direct evidence of the concrete consequences of a particular plant, three important primatologists have found the most important test so far: monkeys treat a group of diseases themselves.

Since the 1970s, Richard Wrangham, professor of anthropology at Harvard University, and Jane Goodall, the most prestigious chimpanzee observer, have accurately collected the behavior of chimpanzees during food at Tanzania's Gombe Stream National Park. South of Gombet, in the Picos de Mahal National Park, Toshida Nishima, a zoologist at Kyoto University, has conducted similar research on chimpanzee eating habits. Scientists received what chimpanzees ate every day and throughout the day: Gomben catalogued 146 plant species in the diet of chimpanzees and Mahal chimpanzees ate plants of 198 species.

His studies focused especially on a plant genus called Aspilia. This plant was consumed in very few cases by chimpanzees. In African meadows there are several species of Aspilia. Tall plants are an unclassifiable part of the solar flower family. Wrangham's attention was because he had never seen animals as Gombe's chimpanzees played with Aspilia.

Over the last two decades, Gombe observers have studied about 50 animals (from 2 years old to older), who have seen special trips from their traditional dens and pastures to feed Aspilia with their leaves. Wrangham saw dawn eating two specific species: Aspilia plural and Aspilia rudis. The chimpanzees of Mahal of Nishima ate another species: Aspilia mossanbicensis and eat at any time of day. Chimpanzees did not pay attention to the other two species of Aspilia growing in the area. “Normally chimpanzees took the leaves (as a protein additive) as soon as they could by the branches and put them in the mouth, chewed them immediately,” Wrangham said.

“But two-reserve chimpanzees select the Aspilia leaves more attentively and very slowly, closing the lips around the leaf – sometimes for a few seconds – and staying there without removing the branch. When someone dares to eat, the primates put in the mouth a sheet similar to that of liz paper and then (as is not usual for chimpanzees) swallow it whole, before slowly choosing the next”.

Chimpanzees normally eat much faster: researchers found that the leaves of the tastiest plant, the lobulata Mellera, consumed 44 per minute on average and those of Aspilia, only 5 per minute.

These leaves were rarely eaten in chimpanzees, so primatologists studied chimpanzee excrement. In more than 400 samples entire Aspilia leaves appeared, sometimes folded in half. Excrement began to be studied in 1964 or when Goodall began to take samples for seed analysis. (Ironically, Wrangham said, Goodall was the first to analyze the “pill” phenomenon, but at that time he didn’t know what to do with it.) Because chimpanzees took them without chewing, scientists didn't know or took them to feed or get more fiber. But then, analyzing the leaves in the microscope, it was observed that the leaves had small holes that allowed to release significant chemicals when passing through the intestine.

“As in 1983 we discovered Toshida Nishiza and myself, Aspilia could be a stimulating food,” Wrangham said. However, subsequent studies showed that, after ingestion of Aspilia leaves, chimpanzees did not eat more (or less). Primatologists also thought that chimpanzees could eat Aspilia only at certain times of the year, as with many other foods, depending on what there was to eat.

But excrement samples showed that chimpanzees could eat both in January and July. Another possibility was that Aspilia was addictive, sedative or curative. Some chimpanzees, apart from pulling or wrinkling the nose (as if they had ingested a bad taste pill) did not present another type of significant behavior. (Wrangham also performed a taste test, thinking that both humans and chimpanzees avoid harmful flavors normally. However, it did not detect anything usual). Scientists were surprised: What chemical incentives did chimpanzees get? they wondered.

Seeing to what extent the administration of Aspilia as a drug was widespread among the population, researchers thought that chimpanzees could also take them as medication.

Locals made tea with leaves to heal wounds, burns and other skin diseases, as well as to cure stomach discomfort, often caused by worms. Both chimpanzees and humans share three species: Aspilia mossanbicensis, Aspilia rudis and Aspilia plural. Some species that are not taken by chimpanzees are also not taken by man. Both prefer leaves than any other part of the plant. “It seemed that chimpanzees and humans shared this issue,” Wrangham said.

Although for Wrangham Aspilia (especially the species preferred by Mahal chimpanzees) is one of the most popular remedies in Africa, no one has analyzed the chemical composition of plants to find out what the active ingredients can be. For this information, Wrangham turned to Eloy Rodriguez. At Irvin, at the University of California, she is a pharmacologist and expert in this plant family, Composite.

Rodriguez's results were surprising: leaf pills had a high concentration of a powerful antibiotic called tiarubina-A. This bright, red chemical was previously found in the roots of another plant in the Chaenactis douglasii family of the same family. In Canada the locals with these roots make a healing for skin wounds.

But the chemists knew that tiarubin was also found in the young leaves of the plants of this genus. “I was surprised by the knowledge of the chimpanzee and the Africans. They thought that this chemical is only the young leaves without the support of higher education,” Rodríguez said. However, chimpanzees only receive leaves of two species at dawn and at that time they may think they know they are more effective. This is quite likely as the second concentrations of plant metabolites often follow the daily cycle.

Rodriguez discovered that the substance is a potent thiarubina-A fungicide and a charming agent: the substance in very small doses (5 parts per million) is fully effective against a variety of parasitic worms. The compound has antibacterial and antiviral properties and is more potent than the drug vinblastine against cancer in vitro toxicity tests. That is, the first chimpanzee meal known with a high concentration of bioactive drug, according to primatologists.

The Maya of Chimpanzees

Wrangham and Goodall suggest that taking plants as drugs is another feature that chimpanzees are smarter than other primates. “Chimpanzees learn by looking at and imitating older foods and learn new behaviors for immediate use,” says Wrangham.

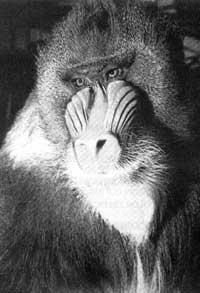

This characteristic distinguishes chimpanzees and other primates of Gombe (such as mandreles), since these also usually take medicinal plants from time to time, but at least apparently only as food and not for another reason. Although Aspilia has raw leaves, mandreles quickly chew like any other leaf and this feature shows that they chew them like anything else and that mandreles can destroy the toxicity of chemicals in the stomach. “It is surprising,” says Wrangham, “that for 20 years we look at the mandriles and see Aspilia eating only two and not as chimpanzees.”

Other animals sometimes take advantage of the antiparasitic characteristics of some plants, but not for internal diseases. Araba blackbirds, for example, control parasitic infections of their nests by fodder with certain leaves. But in addition to the chimpanzee, other animals do not have the ability to unite the intake of certain plants and cure some disease or disease, or to find different solutions to a problem. Unlike Mirlo Álava, the chimpanzee is a differentiating consumer, who chooses three species of Aspilia and that at different times of the day, when the chemistry of the plant changes, seems to have in mind a question of quality.

Moreover, Wrangham and other primate-experts have found that Tanzanian chimpanzees capture other medicinal plants and treat Aspilia as the leaf. One of them is Lippea picata, a forest bush. In Mahal, the primatologists saw how a female chimpanzee devoured the leaves of this plant and quickly went to rest. The tongwes crushed the leaves of this species and teared to eliminate stomach pain. Elsewhere in Africa, people take other Lippe species to cure malaria and dysentery. As can be seen in the analysis, Lippea contains powerful compounds called mototerpanos, which are probably active against a group of parasites.

The aforementioned sick female also took another plant: Vernonia amygdalina. It is another forest shrub that serves to heal. During tropical Africa people use this plant to treat parasite pests. The Vernonia analysis showed that it contains antibiotic and antiviral agents, as well as elements that could strengthen the immune system. This fact has been the first in which the healing of the chimpanzee appears related to self-medication. Two primatologists, Michael Huffman of Kyoto University and Mohamedi Seifu of the Mahal Mountains Faunistic Research Center, published last year the detailed study of the behaviors of this female chimpanzee.

According to Huffman, the chimpanzee was lethargic and seemed to have diarrhea (a common symptom of parasitic infection).

He abandoned the sweet trunks of Pennisetum purpureum by eating other chimpanzees and searched for the bitter juice of the young plants of Vernonia amygdalina. Instead of eating whole plants, the chimpanzee absorbed the juice and threw out what was left. Then he rested in the nest of the tree, with his chimpanzees nearby. In 24 hours, the sick chimpanzee returned to the normal rhythm of life.

“Even though chimpanzees cannot show that they self-medicate, taking into account what this and other Japanese reports say, these primates face a timely problem, in this case the disease,” says Wrangham. “There is no evidence that other animals, not even the mandreles, do this.” Following this reasoning, Huffman began to observe the state of Mahal chimpanzees full of parasites. The first results obtained from the analysis of manure seem to indicate that some chimpanzees carry enough parasites to produce uncomfortable symptoms. This discomfort, in his opinion, can push chimpanzees to start looking for remedies.

As Wrangham has discovered, chimpanzees from other communities and reserves outside Tanzania also use a large number of medicinal plants: In the Eastern Uganda Kibale Reserve he has identified several species of chimpanzees that are devoured by chimpanzees, not chewed but whole, and are also traditional African remedies. Rodriguez has analyzed many of these plants and found evidence of their pharmacological impact.

The leaves of a local rogue (Ficus exasperata), for example, contain well-known anti-bacterial and anti-fungal components, which the Egyptians used since ancient times to treat skin diseases. Chimpanzees take these leaves in their normal diet, but probably in this process they take advantage of pharmaceutical properties. Rodríguez has also isolated a small polypeptide from Rubia cordifolia. This plant is a common remedy for stomach pain in Uganda, active against parasites and, according to Japanese researchers, also affects tumors.

In both Uganda and Mahal, chimpanzees engulf more than chew raw leaves from an herb called Commelina. This herb contains tannins and a milky substance. Africans use it as a general antibiotic and anti-virus to treat fever, eliminate ear pain and even stop bleeding. Rodriguez is analyzing the sheets to find her active accessories.

Americans are especially interested in developing effective fungal treatments, as they are treatments that are missing from Western medicine. The Japanese are more interested in Vernonia's ability to strengthen the immune system. If Aspilia is effective against worms, according to Rodriguez, it can be an alternative to expensive synthetic drugs and more suitable for treating people and livestock in the Third World. Meanwhile, primatologists have many other headaches to solve: how chimpanzees are developing the ability to select medicinal plants, and why Gombe chimpanzee females eat the Aspilia plant three times more than males.

There is also the question that only these potent chemicals act together with other plant agents. The task is enormous: According to Wrangham and Goodall, there are 27 meals occasionally eaten by chimpanzees for analysis. To do this, Rodríguez Wrangham teaches his students of primatology plant chemistry techniques.

“This is what really surprises us,” says Rodriguez, “it’s not just about having clear proof that chimpanzees self-medicate. It’s about showing us what new potential drugs can be from your forest pharmacy.”

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian