Equipment Security

When it is observed that the population of some animal species is very small, protective plans are developed that include the protection of the animal itself and the protection of the environment. And with this, we hope that the animals are calm and begin to reproduce and recover the population. But often populations do not recover as desired and researchers have to think about something else.

When the number of animals is very small, a good strategy can be to capture everyone and try to reproduce them in captivity, for example in zoos, to better control things and ensure the right result. However, it is often not possible to get reproduction, as often animals do not even try to do so. Why? can think of someone. The answer is quite simple, as in addition to the place and food, they need other suitable conditions.

Man is a social animal. In general, it develops better in the group, but they are also able to reproduce men and women who do not live in it. The wolf is also a gregarious animal, and if the group is large, larger prey will be captured. But there are also isolated couples who raise and advance.

Many other species, however, are not able to reproduce if they are not in group or the size of the group is insufficient. For example, the blue whales walk alone throughout the year and when the breeding season arrives they start looking for a partner. If they are insufficient, they will occur less, although we take good care of the environment and protect the species. In short, they will have difficulty finding a partner.

The case of the New Zealand parrot slave is more curious. During the breeding season several males gather in one place and begin to exhibit and sing. The females will approach these places and choose the male they consider most suitable. If not collected as many males as necessary, they will not be able to attract females and, in the absence of them, they will not be able to reproduce. In Europe something similar can happen, as in recent years the population has decreased considerably.

If necessary, the problem of whale and beetle can be of quantity and, perhaps, it would reproduce with males and females together. But what happens to animals that gather to protect each other is more striking. Flamingos and penguins will not go into heat if there are not enough couples able to reproduce around. In species with this behavior it is very important that the breeding season is well synchronized, since if there is a lot of breeding around it, the own can survive. However, this strategy is adequate while the population is composed of a large number of individuals, but it can become a problem if for any reason the number of specimens is considerably reduced. And if you want them to reproduce in captivity. It seems that psychology has a great importance. That is why it is very difficult to obtain suitable populations from small quantities of flamingos and penguins, or that they reproduce in captivity.

The

case of African Licaon is more difficult and complex to observe. Likaona is one of the greatest extinction risks in large African carnivores: in some protected areas the population declined by 30%, despite the increase in other species. Likaon has a very special social life. When they reach the age of reproduction of the young, six people of the same sex come together to form the group and leave the group in which they were born. When it comes to finding a newly created group of other sexes, the two meet and establish what will be the main pair of them all. If the groups are too small, that is, the breeding couple and only four or five adults, there are not enough companions for the hunting and care of the offspring, so the growth of the offspring will be less. And if there is no large group in the environment, they will find it difficult to increase the population.

Mangosts are

also very social and use companions to grow. It has been seen that when groups are small they die much more offspring. And, therefore, they would be in the same state as the licaones.

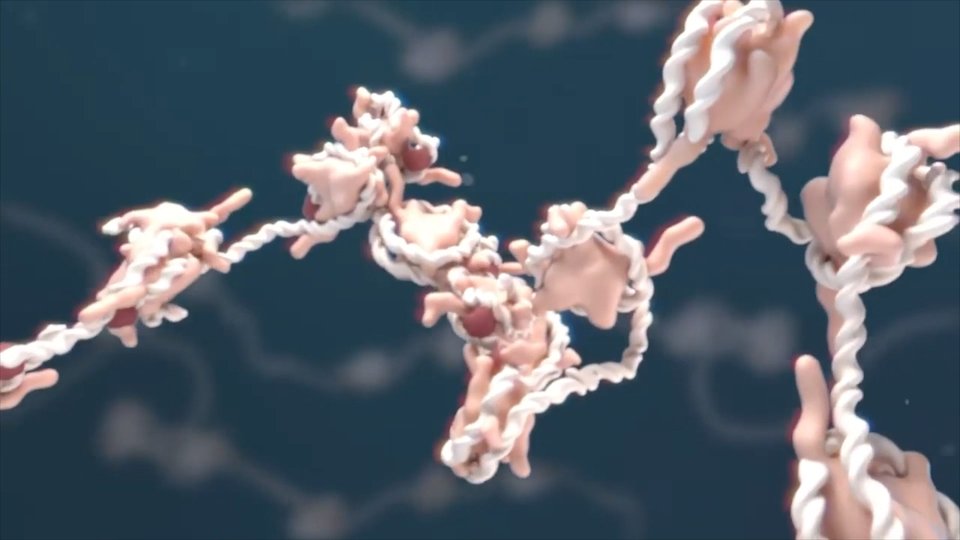

These and other examples show that certain animals cannot be protected in limited quantities and other conditions must be taken into account. Sometimes the support offered by the group ensures the success of reproduction and breeding. If the group is not large, couples will multiply, but they will not succeed and many offspring will die. However, on other occasions, for reproduction a different group is necessary. Without such groups, there is no reproduction. That is, that in nature the equation "1+1 = X puppy" is not always fulfilled, although the environment is propitious and abundant.

End of the American Migratory Pigeon

In

our case there are many hardened pigeon hunters, there is no denying. But, apparently, it's not just about here. Migratory pigeons are not here alone.

In North America there was a kind of migratory pigeons. It is said that at the beginning of the 18th century, early colonization, the continental eastern skies were completely blackened during the passage, up to three days for the group of pigeons to pass through a certain place. And hunters at ease, how not. It was enough to place the shotguns up, point to the center of the group and shoot. More and more of a dove fell.

When they sat on the trees, the branches broke with the weight of the weight. It is estimated that they were between 3 and 5 billion, the largest number of birds of the same species in history.

In the 1890s, however, this species of pigeon was practically extinct. When there was no longer a dove in freedom, economic prizes were offered to those who announced one or the other. No one received this award.

A

few pigeons had in the zoos, but they did not reproduce and the final pigeon died at 13:00 noon on September 1, 1914. Although they had males and females and made efforts, they did not get them to reproduce. Probably couples of this species of pigeon needed other breeding pairs in their environment, or to properly complete their reproductive cycle needed more pigeons than those existing in the zoo.

Published the supplement Natura de Gara

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian