“Protecting natural spaces cannot lead to a decline in cultural diversity.”

The environmental economist Unai Pascual García de Azilu has been researching man’s attachment to nature for many years. On this occasion, he has studied the material contributions of nature to our survival, in order to also reveal the other consequences that the destruction of nature would have on people. The work will be presented at the Conference on Biological Diversity, which is currently being held in Montreal: they will propose which natural spaces should be protected within the 30x30 strategy. But they also have another objective: to include the variable of cultural diversity in the negotiation.

You have mapped the sites that should be protected from the perspective of the material contributions of nature. For what purpose?

this is a continuation of an article we published in 2018 in the journal Science, the second hit. In it, we received the contributions of nature to man, and this time, we focused on the 14 important contributions. Exposing the purely intrinsic values of nature is, in practice, not enough to take measures to protect nature. We continue to destroy nature. But there is another pragmatic reason to preserve nature: to protect people and their well-being. It is not only because we like nature and it is morally important; the destruction of nature has terrible consequences for people.

Therefore, we wanted to identify where the natural spaces that are critical to humanity are located, as long as they make material contributions to the human being. To do this, we had to define the very concept of “nature’s contribution to man” in 2018. We often talk about ecosystem services, but we have seen that this concept is very small and that the contribution of nature must be understood in a broader way.

What contributions have you considered?

There are 14 vital contributions: the habitats of pollinating insects to ensure agriculture and human nutrition; the ability to contain sediments to prevent them from being carried by water; the ability to collect nitrogen to ensure water quality; fodder for livestock; timber production for construction; timber production as fuel; flood containment; freshwater fishing; marine fisheries; natural areas used for recreation; marine recreation; and the ability to protect against storms at sea. These twelve contributions are local, the contributions of nature to those who live in the area. And there are two other global ones: The ability to regulate climate change through the storage of CO2, and the recycling of atmospheric moisture (regulated by vegetation). It is true that nature makes many more contributions to us, but there is not enough data to map the whole world, at least for now.

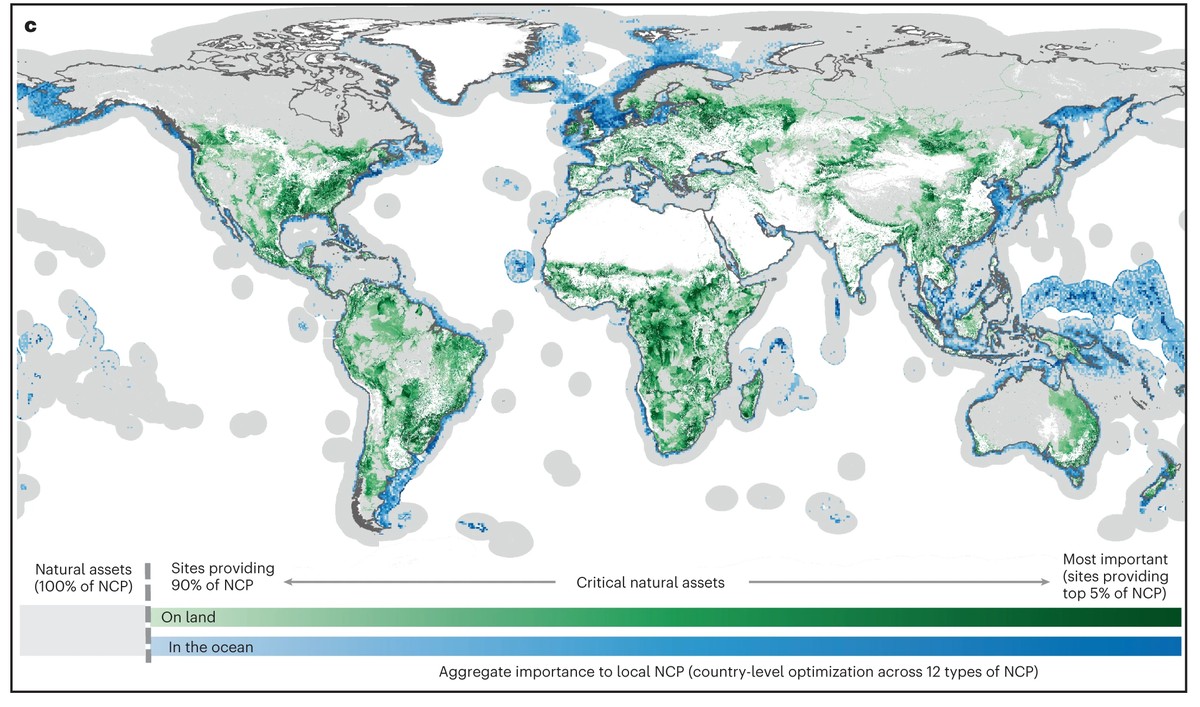

The map of the world that we have completed shows the critical active sites of each state that guarantee 90% of the contributions of nature in that state and, therefore, must be protected as a priority. For example, the Stone of Aia can be an area: it manages to retain sediments, acting as filters; there are very important habitats of pollinators

And we’ve seen that 30% of the earth’s crust is home to 90% of all the resources that humanity—local society—benefits from. And taking into account the contributions of the coast, they are concentrated in 24% of the coast and the surrounding water surface.

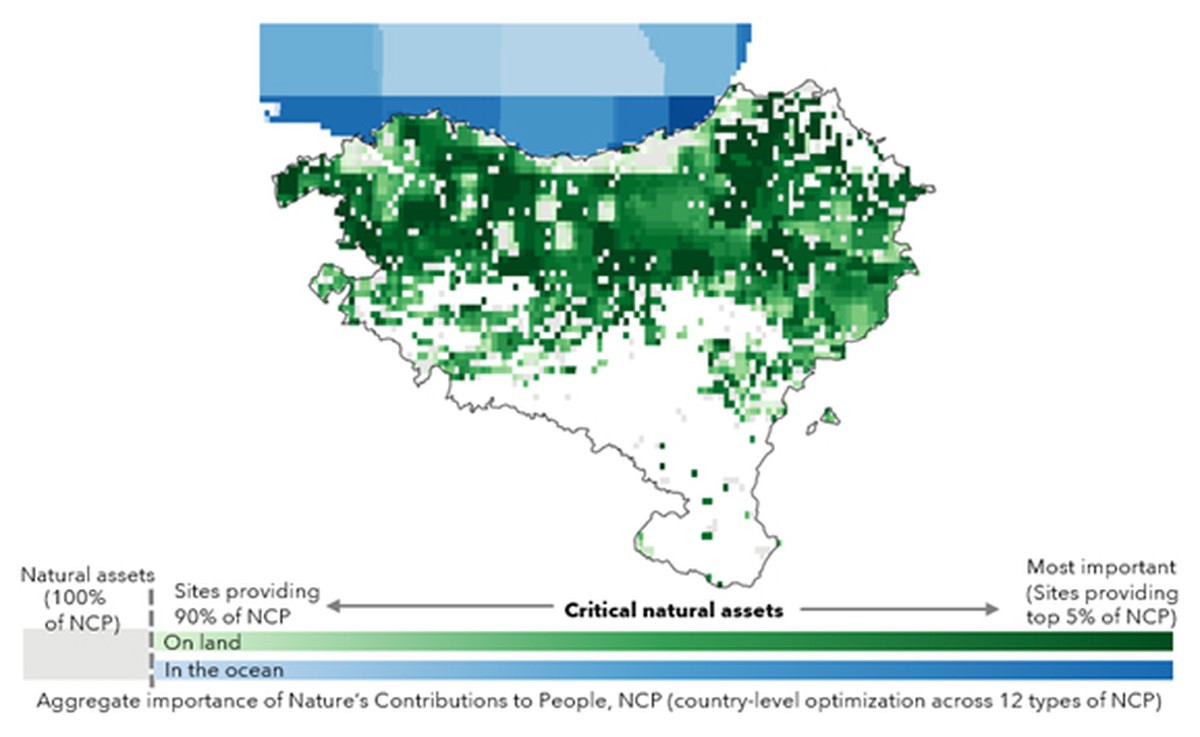

Where are these critical active sites located in the Basque Country?

A zoom in the global map that we have completed shows that there is a large area of the Basque Country within these critical natural spaces. Most areas make many of these twelve contributions. Only urban areas, less than half of Navarre and some areas of Álava, such as those with intensive agriculture, are excluded. In fact, we have considered natural or seminary spaces.

There are still issues to be refined. For example, the map of the Basque Country highlights Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia, as well as the area covered by pine trees, whose intensive forest plantations are as denatured as the potato plantations of Álava.

On the other hand, it must be taken into account that the global map that we have completed includes information from the states. In other words, in this map, the reference is not the Basque Country itself, but the states. We must be very careful when interpreting maps.

Why have you adopted a national reference for mapping and not the most valuable ecosystems in the world? That’s going to change the picture a lot, right?

We have done so in the belief that it is more useful to bring them to the decision-making points at the political level. The United Nations cannot decide what to protect in the world. Such policies are generally national in nature. Within its competence, each State sets objectives. With maps like this, everyone would know what they should protect. In the Basque Country we find it difficult because the competences are divided into several administrations.

You mentioned that in 30% of the earth’s crust, critical active natural spaces are concentrated. Would it be enough to protect 30% of the Earth?

Yes, and no. Yes, in order to be able to maintain these specific local contributions. But there are many more contributions that we have not been able to map yet. The most important thing is not the map we have created; the most important thing is the exercise itself. We have created a methodology to be able to do this, and we have seen that it is possible. With big data and the computing power we have, better maps will come in the future.We have opened the possibility of mapping more contributions that nature makes to us.

There is another interesting fact: in order to maintain global contributions, such as those that help to combat climate change, the area to be protected increases considerably.

That is, when it comes to global contributions, if we want to keep 90% of each state’s contribution, we should protect 44% of Jadadik land.

Forestry in the Basque Country would be very important. if sustainable forestry is carried out, these lands would have a high capacity to cope with climate change.The question would be: will existing forest models be able to perpetuate these contributions over time? This is where we should focus the discussion.

You have also studied who lives around the active areas to be protected, haven’t you?

Oh, yeah, yeah. When you look at these maps, the first question that arises is: how many people live around this critical 30% of the world’s land surface? Well, of the 8 billion people in the world, 6 billion live not inside the zones, but around them. In total, 80 per cent of the world ' s population directly benefits from contributions from these sites. It is therefore imperative for humanity to protect these areas. Not only because we like nature; it makes contributions that are very important for our well-being.

Another question is how many people live within that 30%. Much less so: % 16. There are usually small local communities, indigenous communities... and what cultural diversity is there? Well, that's terrible. We estimate that 96% of the minority languages are there. In other words, critical active natural spaces and areas of greater cultural diversity are superimposed.

What’s more, they overlap even with the most biodiverse areas. This creates a solid framework for deciding which areas should be protected: protected by these areas, in addition to these material contributions to humans, we would also greatly protect biodiversity.

And what are the implications of having spaces with greater cultural diversity?

Due to the great cultural diversity in these places, it is likely that there will be a wide variety of cultural values: different lifestyles, other forms of connection with nature... There will be values inherent to this land and different experiences with these contributions of nature. Right now, there's a 30x30 debate in Montreal: whether we will protect 30% of the world’s land surface by 2030. How will they be protected? What policies will be designed? Who on the ground will have the say and the opportunity to answer these questions? It will not be easy to agree either in Montreal or in local contexts.

For example, in the Amazon or Africa there are many of these active natural spaces. Do we have to expel the people who live in them to protect those areas that we have found interesting? That shouldn't be an option. Nature cannot be protected in a neocolonial manner. The protection of natural spaces cannot lead to a decline in cultural diversity. We will have to integrate the way of life of these people, their values, culture and character into the protection strategy, taking into account that these natural spaces have historically been integrated into their way of life and continue to be used for their livelihood. All this will have to be managed. There is and will be the biggest debate within the 30x30. If a 30x30 political agreement were to be reached in Montreal, this variable should be included.

What is the next step that science has to take?

I believe that in this effort to identify critical natural spaces, it is necessary to carry out scientific research that combines the social and ecological fields. It is necessary to investigate where poverty is, what type it is, what inequities there are in these areas... It is necessary to integrate the map of socio-economic inequalities in the ecological maps that we have now created.

The problem is that socio-economic and cultural indicators are usually not in the 2 km2 resolution that we now use. Ecological, but not socioeconomic. In the case of poverty, education and health, for example, the level of resolution is much lower. Usually, most countries only publish averages. Therefore, it is necessary to give a boost to the agencies that measure such variables. In this way we will be able to see the extent to which critical natural spaces such as poverty overlap. We will know the characteristics of the people who live in these environments. And what they need. If the implementation of the 30x30 strategy is decided at the global level, the integration of the socio-economic variable is mandatory.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian