Journal cover Nature for a Basque researcher

Xabier Irigoien is a 35-year-old Hondarribiarra. He studied biology at the University of the Basque Country in Leioa; completed his studies in oceanography at the University of Bordeaux, where he studied both the master's and the doctoral thesis. He studied for two years at the Institute of Marine Sciences in Barcelona and has spent the last 6 years in Britain.

At the Plymouth Marine Laboratory and Southampton Oceanography Centre, Nature has done the research it has just published. Currently, Xabier Irigoien works in Pasaia, AZTI Foundation, after obtaining the Ramón y Cajal scholarship for 5 years.

The research was conducted in collaboration with oceanography and research institutes from five other countries. This is a study on zooplankton, more specifically on the reproduction rate of copepods.

Copepods and fish production

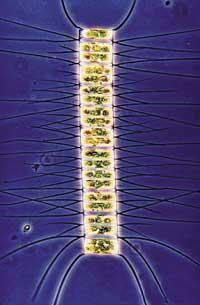

Copepods are microscopic animals that live in the sea and have great importance in the basic food chain of the sea. They feed on microscopic algae, mainly diatoms, so they can be considered herbivores. At the same time, small species of fish feed on copepods and large fish. Copepods can therefore be considered binding points between algae and fish.

Biologists have long studied the relationship between copods and diatoms, a relationship that directly affects commercially interesting fish populations and marine ecosystems in general.

According to the model that has always been approved, the growth of the population of diatoms positively influences the population of copepods, that is, more diatoms, greater presence of copepods in the water. This will have positive effects on the fish population.

However, some laboratory trials have found data suggesting that this model is not entirely correct. In laboratories, several researchers have found that the proliferation rate of diatome-fed copepods decreases. This would mean that high concentrations of diatoms negatively affect copepods.

It should be noted that the abrupt growth of diatoms in the sea usually occurs cyclically. If high concentrations of diatoms affect the reproduction rate of copepods, the copepod population decreases and, in turn, fish populations.

Answers obtained

Irigoien, along with his colleagues, has tried to show that what was observed in the laboratory also occurs at sea. To do this, samples of diatoms and cocopepods have been taken in areas of high marine production, analyzing the relationship between the concentrations of both. According to the data obtained, diatoms have no negative effect on marine copepods. Therefore, there are no, at least in this sense, reasons for aggravating copepod populations.

However, it is still unclear why diatoms negatively influence laboratories. Irigoien and his team propose two hypotheses to explain the drop in the reproduction rate of laboratory copepods.

According to the first hypothesis, the diet of copepods in laboratories can be the cause of the problem. They feed animals only with diatoms and this diet can be deficient. In the sea, the copepod diet may be made up of other nutrients than diatoms.

The second hypothesis refers to the toxicity of diatoms as a cause. The high concentrations of diatoms used in laboratories can be toxic to copepods. According to data collected by Irigoien and his team, the sea has not measured such a high concentration of diatoms so far, so it seems that copepods have no risk of poisoning.

Irigoien's research is part of a broader project called GLOBEC. The project analyses the effects of climate change on marine ecosystems and, in particular, on zooplankton, such as the abundance, diversity and production of their populations.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian