The evolution of Basque translation in the light of technology

Let’s try, for a moment, to imagine Joannes Leizarraga, in the 16th century, working on the Bible. It probably had a pen, ink bottle and paper on the table, and a Latin translation in front of it, placed in some sort of vestibule. It has been five centuries since the creation of what is considered the first translation in Basque, and things have changed very well as they have changed...! But perhaps more than one reader will be surprised if we tell them that some translators who are still active today did not make their first translations under such different conditions. In fact, most of these characteristics that we have mentioned were part of the daily life of Basque translators until about forty years ago: in addition to the translation, the notebook and the pen or pencil, they only had some sort of consulting dictionary on the table (and these, of course, also of paper). They did most of the work by hand and, after sewing the pages of the notebook with scribbles and finishing the work, they used the typewriter to move the final version to the clean.

If we had to chronologically count the following changes since then, we would inevitably have to mention several tools that have been milestones for the translators’ performance: computer, CD, Internet... and, of course, the language technologies that have been developing more and more rapidly for decades. Let's go over it.

From physical desktops to virtual desktops

The translators worked as described until about the mid-1980s. In that decade, however, personal computers came to us and soon became one of the working tools of many translators. Not surprisingly, there is a difference between working on sketchbook pages and seeing what is written on the screen always clearly, even if the same sentence is rewritten four or five times.

The translation magazine Senez was also born at that time, in 1984, and since its inception has witnessed the main trends that have been in full swing among Basque translators. It can be seen, for example, that the word computer was first mentioned in 1985,[1] and computer two years later,[2] as a "useful tool" for translators. At first it was not available to anyone to have a computer at home, but in a few years it became not only a useful but (almost) indispensable tool.

Underlined words and immediate consultations

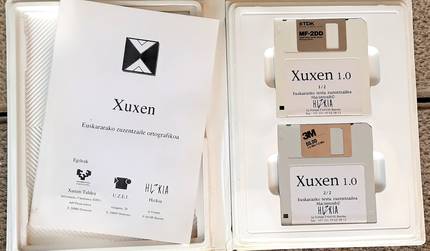

The transition to the screen has not yet been made by everyone, and what it is, and immediately other resources began to appear that would completely change the work of the translators: orthographic proofreaders and, unified with them, electronic dictionaries. Xuxen was the first spelling editor in Basque,[3] and was released in 1994, initially in diskette format. Anyone who works in the textiles industry knows perfectly well how much help they give, because they warn of what to pay attention to by insisting on words that could be incorrectly written. But Xux didn’t come at any time either: it was only two and a half decades since the creation of the united Basque language, and the rules of writing were still being set. Therefore, they were a great way to help spread these rules among translators (and many other speakers).

In terms of vocabulary, Dictionary 3000[4] and Elhuyar's electronic dictionary[5] were among the first to appear in CD format, both in 1996. The task of carrying out the queries was greatly facilitated: what could only be searched on paper according to the dictionary entry, could now be searched according to the grammatical category, subnets and other characteristics, much faster than before and without turning pages backwards.

A Network, the World Wide

However, the flood of diskettes and CDs did not last long: before the arrival of the new millennium, the Internet exploded and, in a short time, it became the main support for a large number of sources of information. From then on, not only proofreaders and dictionaries began to appear, but also other linguistic resources, such as searchable corpus. The Basque Government made available the statistical corpus of the Basque language of the 20th century,[6] the UPV/EHU Model Prose Today,[7] Elhuyar and the research group Ixa made available the ZT corpus[8] and Corpeus...[9] So to speak, the searchable corpus allows translators to search large collections of texts and, nevertheless, to see in the dictionary entries many other examples than those that come.

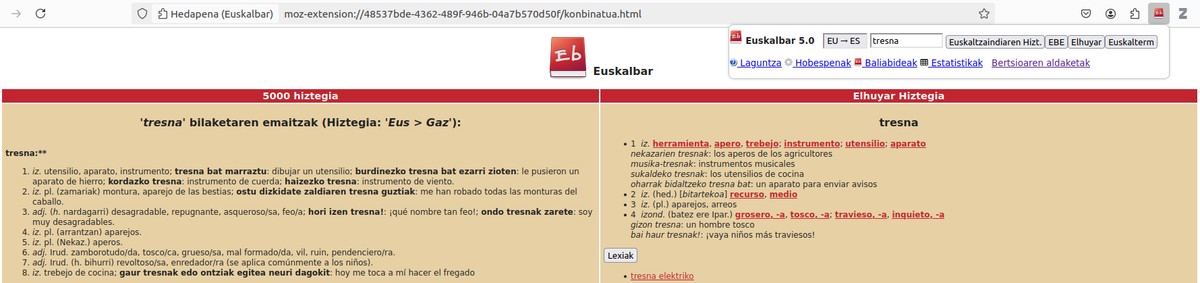

We could also mention more resources co-created with the beginning of the millennium, but let’s bring at least two more to this brief review: ItzuL mailing list[10] and Euskalbar. [11] The first one, created by the EIZIE in 2004, actually has a relatively simple technology behind it; a mailing list is simply "something else", after all... It’s no small help for translators: if they can’t answer any questions, they have the forum to ask and the exchange of opinions by e-mail begins immediately. Euskalbar, on the other hand, is a browser installation add-on, created in 2006, which allows language queries to be carried out simultaneously in different media. In the first version, searches could have been made in four dictionaries, but as new resources have emerged, the tentacles of the supplement have also expanded. At present, ItzuL has more than 900 subscribers and Euskalbar provides access to more than 70 language resources, which are not bad numbers, right?

Memories outside the brain...

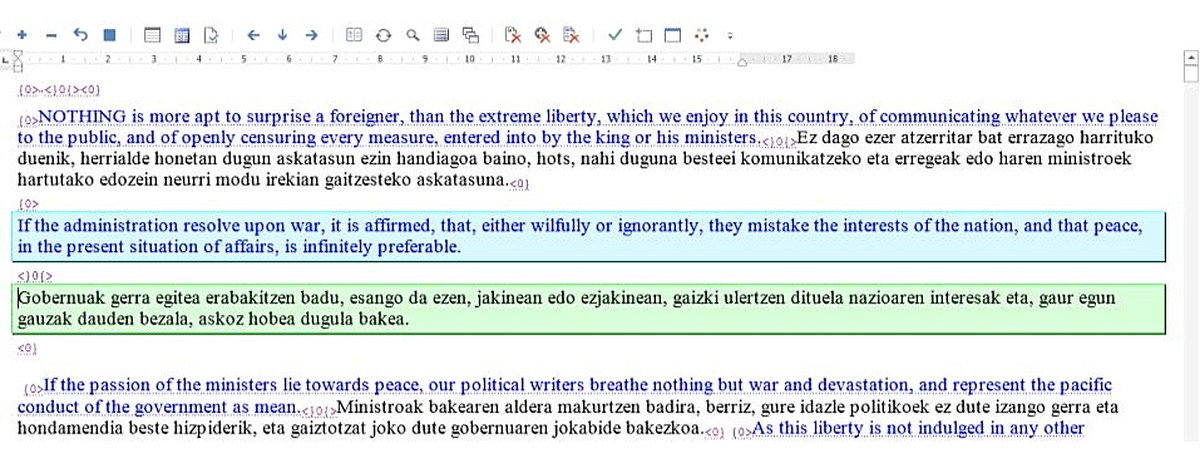

Translation memories also began to be incorporated into the computers of Basque translators during the millennium change, and today there are hardly any translators who do not use them. To put it briefly, there are several programs that store the works of the translators in a structured way and convert them into memory, with texts in both languages in pairs: divide the translator by segment (approximately, sentence by sentence) and record how the user has translated each of them.

Not only that, but they remember. In fact, as one progresses in the work, one searches for previously translated texts and, if one ever sees that a similar segment has been translated, they show the translation of that time as a suggestion.

In general, translation memories (and glossaries, etc., used in conjunction with them) benefit the internal coherence of translated texts, and if they are placed in the shoes of those who translate texts with relatively rigid and repetitive structures, it is easy to understand why they have spread so much in a short time. However, we would be lying if we said that they are ideal for all types of work: to translate poetry, for example, it is obvious that it would not make much sense to translate the text in parts by parts. For this and other similar reasons, they have also been criticized; above all, that they limit creativity, because if you look at what has already been done, it is difficult to think of other possible translations.

...and the brains outside the person

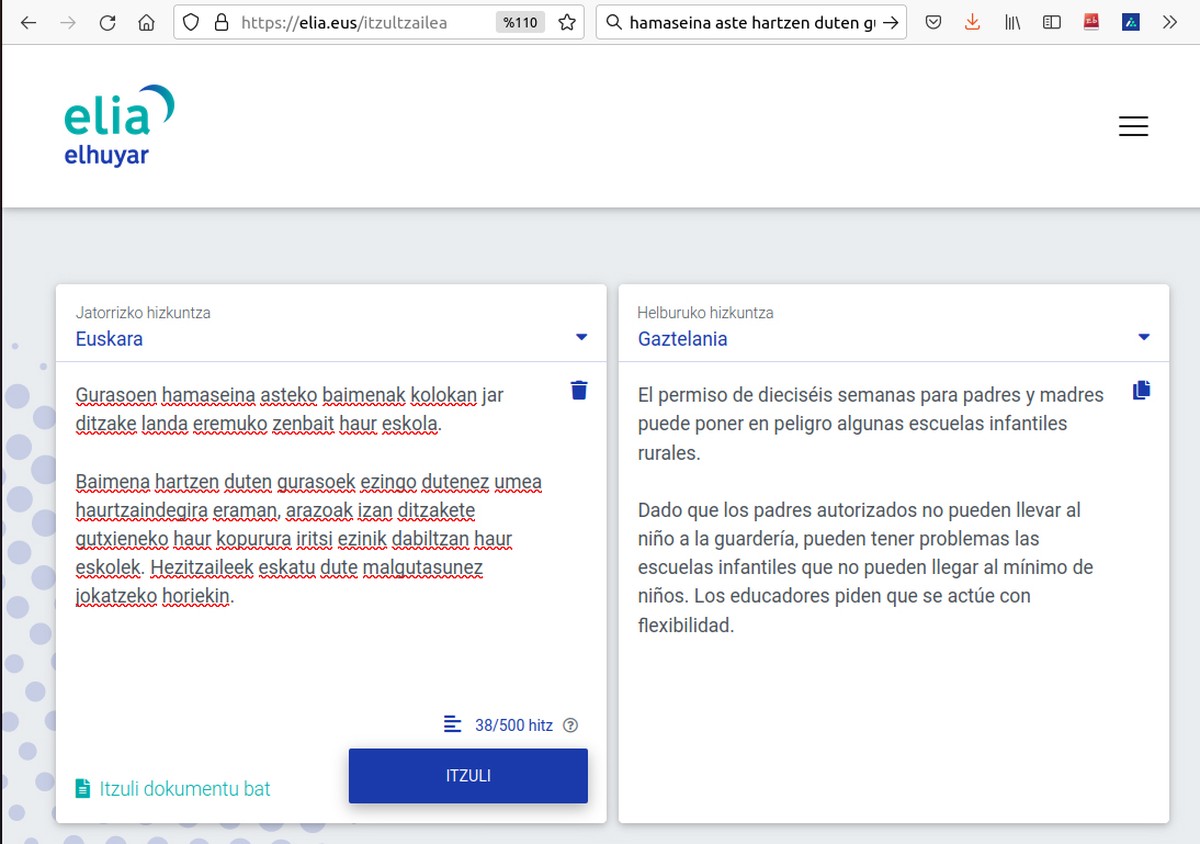

And we come, little by little, to the era of artificial intelligence, today. It should be noted that automatic translators are no longer such a new subject (the first for the Spanish-Basque language pair, Machin,[12] was founded in 2006), but in the case of Basque, those available until recently did not have very good quality and it was almost unthinkable that they would ever be a working tool in our country. In 2018, however, Modela was born,[13] the first neural translator in Basque, followed by current translators such as Elia,[14] Itzulia,[15] and Batu. [16]

It cannot be said that all translators are amateurs (if some people looked at translation memories with suspicion, automatic translators, no matter what! ), but they have them in a growing number of translation services, usually integrated in the same tools of management of translation memories: the priority is the texts that have been translated previously, but if there are no segments in their own memories that correspond to what is being translated, automatic translation is offered as a suggestion.

Some might think about what the person is for then, if the translations are generated by an automatic system... But, even if someone has doubts, let’s clarify that the intervention of the person is still essential in the translation process, and will be, if we want the final text to have the highest level of quality. In fact, they serve to work more comfortably, yes, but the work of correction (or, as it is said in the case of machine translation, post-editing) is a work that must be done using all the senses, so that between the relatively natural results, the changes of meaning do not escape camouflage, so that the language of the whole text is coherent and, ultimately, all the nuances that a professional translator/proofreader takes into account are adequate.

And from now on, what?

At least one thing is clear: the Basque translation community has undergone tremendous changes in recent decades and has been able to adapt perfectly to the contemporary era. Now, if all these changes have been for the better or for the worse... Well, who is to be asked: for those who love to play with language, perhaps a profession which by its very nature has a lot of creativity will be becoming mechanical and non-human, while others will see opportunities in technological advances to reduce mental fatigue and facilitate tasks.

In any case, given the speed of change, we will have to remain cautious in order to take advantage of the opportunities that arise, but also to take into account the risks. In fact, it is one thing to change the tasks that are part of a profession over time, and another very different thing to accept an uncontrolled revolution with a blind eye to digital technologies, without taking into account the consequences that this can have not only on the profession, but also on the evolution of the Basque language itself, among other things, on the habits of use and the quality of the texts.

What would he say if he raised his head...?

The bibliography

[1] Ibarzabal, A. 1985. “VI summer of San Sebastian. The courses.” Instinct: Journal of Translation and Terminology, (3), 141-143. https://eizie.eus/eu/argitalpenak/senez/19850901 [2]

Mendiguren, X. 1987. “The Translator’s Houses in Europe”. Senez: Journal of Translation and Terminology, (6), 241-243.

[3] Agirre, E., Assisted by Alegria, I., Too close, X., Assisted by Artola, X., By Díaz de Ilarrazá, A., Assisted by Maritxalar, M., Sarasola, K. and Urkia, M. 1992. “Xuxen: a spelling checker/corrector for Basque based on two-level morphology”. Third Conference on Applied Natural Language Processing, 119-125.

[4] Five to one. 1996. The dictionary 3000.

[5] Elhuyar Foundation. 1996. “Elhuyar electronic dictionary”. Elhuyar Science and Technology, (114), 44-47.

[6] The Academy of Sciences. 2002. Statistical corpus of the Basque language of the 20th century.

[7] Sarasola, I., The Chief of Salon, P., Landa, J. and Zabaleta, J. 2007. Model Prose Today (EPG).

[8] Elhuyar Foundation and Ixa Group. 2006. Corpus of science and technology.

[9] Elhuyar Foundation and Ixa Group 2007. Corpeus: the internet as a corpus in Basque.

[10] EIZIE Association (d.g. ). The ItzuL mailing list.

[11] Euskalbar (accessed July 1, 2024). From the Wikipedia.

[12] Major, A., Assisted by Alegria, I., By Díaz de Ilarrazá, A., About Labaka, G., Lersundi, M. and Sarasola, K. 2011. An open-source rule-based machine translation system for Basque. Machine Translation, (25), 53-82.

[13] Etchegoyhen, T., Assisted by Martinez, E., The Azpeitia, A., About Labaka, G., In Joy, I., The Cort-es, I., The Palace, A., In Ellakuria, I., Martin, M. and Calonge, E. 2018. “Neural Machine Translation of Basque”. Proceedings of the 21st Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation, 139-148.

[14] Elhuyar Foundation. 2021. Elia.eus.

[15] The Basque Government. 2019. Itzuli.eus.

[16] Vicomtech. 2019. Batua.eus.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian