Recycling faces

Buyers in general, as final consumers, have in recent years demanded more sustainable and environmentally friendly products (Figure 1). A 2019 European Consumer Preference Survey showed that 56% of consumers take into account the environmental impact of purchases, that 67% buy environmentally better products even more expensive and that 81% shop in establishments close to home and that promotes local trade.

While the poor environmental reputation of plastic or plastic products is increasing, the popularity of paper or paper products is increasing, as unlike plastic, paper is renewable and biodegradable. At the same time, the progressive replacement of virgin plastics with recycled plastics is linked to environmental responsibility for the use of recycled materials and the recovery of waste. In this respect, the European Union (EU) has set itself new targets to promote the use of recyclable materials and the recycling of food packaging materials: all plastic packaging to be placed on the market must be reusable or recyclable by 2030; more than half of the packaging waste generated in the EU must be recycled by 2025; in plastic polyethylene bottles for the sale of PET drinks, by 2025%.

It can therefore be said that reuse and recycling can be associated with sustainability, as they allow less exploitation of natural resources and a reduction in accumulation. It is known, however, that chemicals are migrated from materials, increasing the migration of these substances when recycled materials are used.

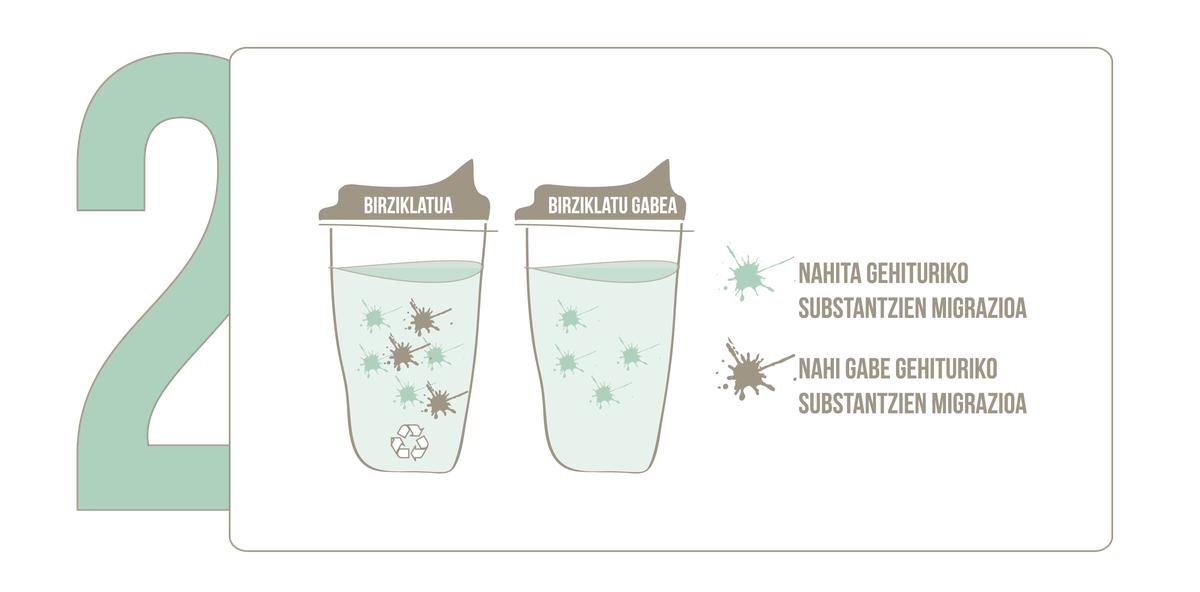

Some of these substances (NGS) are intentionally added to the material, for example: lubricants to facilitate material processing and stabilizers to protect material from degradation. Its use is regulated. Other substances are unintentionally added to the material (NGGS). This group includes, inter alia, chemicals from material degradation in the manufacture and recycling of the product and compounds absorbed by the packaging of the packaged product (food, mouthwash, personal hygiene and household cleaning, cosmetics). Many of these substances are not regulated (little is known about their toxicity or nothing). It has been shown that depending on the type of drugs, the quantity migrated and the level of consumption, these compounds can cause serious risks to human health. Therefore, in the use of recycled materials it is necessary to take into account their application, especially when they may be harmful to human health. One example may be the consumption of substances released from packaging through packaged food (Figure 2).

Almost all the food we buy is packaged. Packaging which is in direct contact with food (primary packaging) is made of, inter alia, cardboard, plastic, glass, aluminium and their combinations, and the food industry selects the most suitable materials for packaging food according to the processing of such materials, the physical and chemical properties, the properties of the food to be packaged and the legislation. The largest number of copies used is paper, cardboard, plastic and glass, in most cases for single use.

Unlike recycling of glass containers, recycling of plastic packaging and paper involves chemical changes in materials (degradation, breakdown of chemical compounds, etc.) They increase the presence of NGGS. They note that less chemicals and fewer types of glass (recycled) packaging are measured than recycled plastic and paper packaging. One of the causes is that repeated recycling of glass practically does not alter the intrinsic properties and purity of the material. Another reason is that, unlike the selective collection of glass, in the selective collection of packaging and plastic paper packaging produced by different plastics for packaging different products (cleaning products, cosmetics, food, etc.). or waste of different types of paper is collected together (paper that has been in contact with food, newspapers, magazines, cardboard, etc.) (Figure 3). This increases cross-contamination, increasing the presence of NGGS in recycled plastic and paper materials.

In general, plastic packaging mimics less substances than paper packaging because of its porous structure. Sometimes a thin layer of plastic is placed inside paper packaging to reduce the migration of compounds. However, it should be noted that this layer of plastic can also release chemical compounds. Experts have noted that, depending on the type of name, migration of these chemicals can be better controlled. For example, polyethylene (PE) plastic has less zone function than PET plastic. On the other hand, it has been observed that chemical compounds can migrate to food from bulk collection materials (e.g. paper trays to carry apples) and secondary packaging (packaging containers to pack primary packaging).

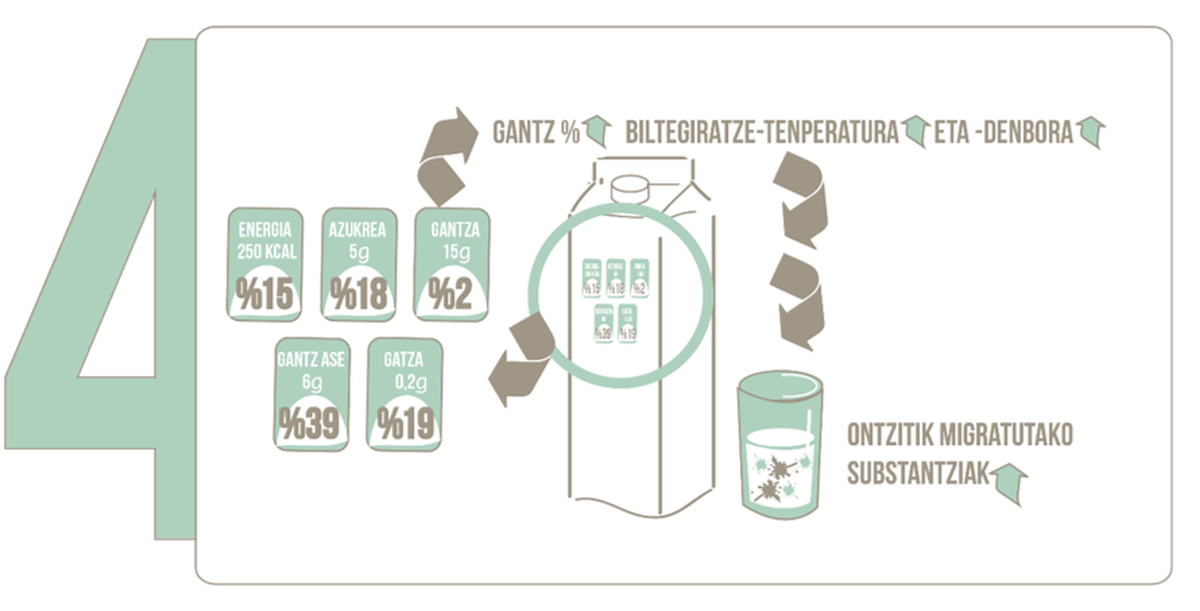

In addition, the composition of the packaged food (amount of fat/water, acidity), the state of matter (solid, liquid) and storage conditions (temperature, time, exposure to light) significantly influence the migration of chemical compounds. In general, it has been shown that the number of samples migrated to food increases with fat content, storage temperature and storage time (Figure 4).

Therefore, taking into account the environmental impact of our purchases and knowing that every day we are exposed to chemicals from different sources (such as those that have migrated from packaging to food), it is clear that sustainability and chemical safety must be worked together to preserve nature and alleviate the presence, migration and consumption of compounds present in materials. With this in mind, what can we do to achieve these objectives in relation to food packaging?

On the one hand, the storage industry, the packaging industry and the recycling industry can take some measures (Figure 5). Among others:

- Facilitate the use of reusable packaging (e.g. facilitate purchase on the floor).

- Reduce the use of additives and all kinds of additives in packaging materials.

- Reduce the use of pigments that make the packaging more attractive. The presence of pigments reduces the number of recycling cycles of the material and some of these substances have been shown to be toxic.

- Design the packaging for reuse and recycling. In addition, reduce the relationship between packaging and food volume.

- The area of the container that will come into contact with the food will be made with virgin material or firewall area, and the rest of layers of recycled material (especially paper packaging).

- When throwing the container in the trash, place a symbol clearly indicating which container to deposit. This reduces cross-contamination and increases the recovery of materials for recycling. This increases the possibilities of reusing food packaging material.

- Improve separate waste collection systems by collecting only materials that have been in contact with food in garbage containers for recycling. If possible, separate packaging from food packaging containing cosmetic and hygiene products.

- Optimize recycling processes. It is observed that improving decontamination and cleaning processes can reduce the presence of NGGS in the recycled material.

On the other hand, as consumers we can consider the following suggestions to reduce the presence, migration and consumption of chemicals (Figure 6):

- Re-use of containers. Buy

products in reusable containers. Otherwise, buy products in packaging of more recyclable materials. For example, the process of recycling plastic PET is more developed than that of other plastics (such as PE).- Buy packaging with few

pigments and packaged food with the minimum of materials possible.- Choose the product that has been packaged closest

to the date of purchase. In this way it is possible to ensure that the food is in contact with the container as soon as possible.- Pass the food through the water before eating or cooking.- Empty the containers and rinse them before depositing them in a trash can to recycle them.- If you want to reuse/recycle the food packaging, use it only to store

the food.

Although the current lifestyle is influenced by many chemical compounds from different sources, research has shown that measures and habits can reduce their presence, migration and consumption, while taking into account the environment. It is clear that we must make changes and that we must all be part of them. Therefore, as consumers, it is up to us to buy responsibly and dispose of the waste generated to recycle correctly. In this, the important thing is to show our willingness to change shopping habits, and to do it one by one.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aurisano, N., Weber, R., Fantke, P. (2021). Enabling a circular economy for chemicals in plastics. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 31, 100513.

Cabanes, A. Fullana, A. (2021). New methods to remove volatile organic compounds from post-consumer plastic waste. Science of the Total Environment, 758

Cecon, V. S, Da Silva, P. F. Curtzwiler, G. W. Vorst, K. L. (2021). The challenges in recycling post-consumer polyolefins for food contact applications: A review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 167, 105422.

Dey, A. Dhumal, C. V, Sengupta, P. Kumar, A. Pramán, N. C. Alam, T. (2021). Challenges and possible solutions to mitigate the problems of re-use plastics used for packaging food items: A review. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 58(9), 3251-3269.

Consumer Survey EC. (2021). New consumer survey shows impact of COVID -19. https://ec.euro-.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_1104

Eriksen, M. C. Christiansen, J. D. Daugaard, A. E. Astrup, T. F. (2019). Closing the loop for PET, PE and PP waste from households: Influence of material properties and product design for plastic recycling. Waste Management, 96, 75-85.

Geueke, B. Groh, K., Muncke, J. (2018). Food packaging in the circular economy: Overview of chemical safety aspects for commonly used materials. Journal of Cleaner Production, 193, 491-505.

Groh, K. J. Geueke, B. Martin, O., Maffini, M., Muncke, J. (2021). Overview of intentionally used food contact chemicals and their hazards. Environment International, 150, 106225.

Hahladakis, J. N, Velis, C. A. Weber, R., Iacovidou, E. Purnell, P. (2018). An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 344, 179-199.

Horodytska, O., Cabanes, A. Fullana, A. (2020). Non-intentionally added substances (NIAS) in recycled plastics. Chemosphere, 251.

Ibarra, V. G., de Quiros, A. Losada, P. P. Sendon, R. (2018). Identification of intentionally and non-intentionally added substances in plastic packaging materials and their migration into food products. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 410(16), 3789-3803.

Ibarra, V. G. Sendon, R., Bustos, J., Losada, P. P., de Quiros, A. (2019). Estimates of dietary exposure of spanish population to packaging contaminants from cereal based foods contained in plastic materials. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 128, 180-192.

Morseletto, P. (2020). Targets for a circular economy. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 153, 104553.

Nemat, B., Razzaghi, M., Bolton, K., Rousta, K. (2019). The role of food packaging design in consumer recycling Behavior—A literature review. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), 11(16), 4350.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian