Adolfo López de Munain: “The gene we have identified is only the first of a whole family”

Do all types of epilepsy have genetic origin?

When I was a student, 40% of epilepsy was considered genetic. But I think the percentage is much higher. Some patients have developed epilepsy as a result of an 'attack': meningitis, birth trauma, accident or tumor. It is a scar that has remained at the origin of epilepsy before a structural problem. But in the rest of the cases I think genetics influences a lot. Perhaps 80% of all cases are of genetic origin.

However, genetics have often been associated with inheritance. But genetic influence depends on the interaction between genes and the environment. For example, some types of epilepsy are sensitive photos, that is, in epilepsies that have not yet emerged, violent lumistic stimuli can cause seizures. If this stimulus is not received, the disease is hidden.

Epilepsy has been hidden in many families, so there are patients who do not know if there have been more cases in the family. On the other hand, if after 25 years the seizures disappear, a patient may forget that he has epilepsy. They are also those who transmit the disease without developing. In these cases the hereditary origin of the disease is hidden.

It is common for patients to experience epileptic seizures in adolescence and disappear at maturity. Why does that happen?

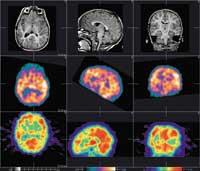

There is no single explanation. The number of crises has two maximums: in adolescence and old age. In the latter the effects of the 'attacks' that have occurred throughout life have accumulated, and those who tend to suffer may suffer crises. Statistically this phenomenon is very evident. The first maximum, however, has genetic origin. In addition, all birth problems also have influence.

Most epilepsies manifest during growth, so the maximum occurs at age 14. When the growth period ends, many of the crises disappear or diminish. For doctors, today, it is difficult to follow this evolution, since patients are normally in treatment, which covers evolution.

How did you find the LGI1 gene?

We have studied a type of epilepsy in a Goierri family. The strategy used for this has been localization cloning. Initially it was clarified in which part of the chromosome this type of epilepsy occurs. Subsequently, the part of the chromosome that affects all cases has been determined by markers to delimit this part. These markers are used in the search for alleles and combining the same haplotypes. Thus, we have analyzed which haplotypes appear with the disease.

In addition, we have searched the gene from fragments of chromosomes identified by other groups, the part identified by us and the one identified by an American group overlaps at one point, so we have limited ourselves to this point to perform a finer search. This part is narrower than the initial one, although there were still many genes to analyze. We look for more families with the same characteristics; we find 10-12 families similar but equal and useful to ours, not one. We then analyze the genes of a receptor and a potassium channel, which may be related to epilepsy. All the results were negative because they were random studies.

Is it possible to facilitate this enormous work?

Yes, we contacted other scientists investigating the chromosome's face: some Germans looked for oncogenes and had many genes identified. So we started collaborating with them. Other groups also participate in this collaboration: Italian, Cretan, etc. Each group has a particular interest in this area, so we share the work: the benign genes would be analyzed by the Germans and the rest by the others.

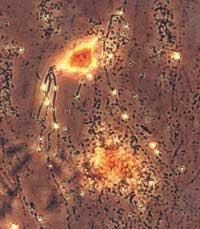

In one of our genes we find epilepsy. In this gene, patients had a mutation that generates a stop codon. Other families with different clinical manifestations did not have that mutation. The consequence is that the disease is not only produced by that gene, but other genes that must be sought also intervene.

Was it easy to publish these results?

It was long. The American team had results of about five years, the work was almost finished and would be published shortly. Therefore, we had to decide: to publish what we had to anticipate or continue the research until we achieved more elaborate results. We offered collaboration to the Americans, but as they had been working for a long time, they wanted to end up without help. We realized that they were about to get our result.

But, in general, the publication of a gene requires mentioning other data: where the protein is, what it does, what it serves, etc. This work is very important, but with the data we had I didn't want to wait.

In December we presented the results in the Spanish Society of Neurology and the American team learned about it. They got very nervous because they had almost the whole article. I was told that on January 16 we discovered the gene and that same day those of the journal Nature Genetics accepted the article. Therefore, we send ours to the same magazine and ask them to decide whether both works should be published at once or what they should do. Nature Genetics is celebrated in New York and, as we expected, they decided to publish their own. But I don't care much.

But three weeks later they didn't accept the article anywhere. Therefore, they sent it to the European magazine Human Molecular Genetics and accepted us, publishing both articles together approximately.

Are your results equal to yours?

We know that we have found a synapse protein. The results are not exactly the same and we believe our results are more correct. Now an opportunity has been created to start collaborating, but it will look: before they did not want, so it is not clear if we will accept collaboration.

But see what science publication is like: Another German group has also obtained these results, but two weeks later. This group has not allowed anything to be published.

From now on, where will you approach research?

We have other families that have nothing to do with that gene but have similar characteristics. Now we have to analyze others similar to the gene found. This gene is only the first of a whole family. Until now, this type of gene was not associated with epilepsy, as it was considered oncogene. The 5 or 6 genes already identified belong to this type of genes, so we want to analyze if there are mutations in them.

Our gene is LDL1. We call it epitenpine: that name is invented by Dr. Pérez Tur and I in a cafeteria in Barcelona… I don’t know if I like it, but it’s there. However, it is probably a family, i.e. there may be 1 epitenpine, 2 epitenpine, etc.

The journal Nature Genetics has explained these days the discovery of another gene related to epilepsy. Is your research similar?

The genes found are related to common epilepsy, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. It's a similar job, but I know they haven't looked for any gender. However, one of the families that they already knew has been studied and because of their structure could be related to epilepsy. This gene participates in the process of forming a type of receptor. He was a "candidate gene" for scientists.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian