Too much happiness from Sophie Kowalevski

By the age of eighteen, Sophie was very clear: she was getting married. She didn't love her boyfriend, but that was the least of it. I knew that this was what a woman of her age had to do and that this was also the most direct way to fulfill her dream.

On the eve of the wedding, childhood memories came to him. And a feeling that he could still feel vividly: the fascination that was caused by those mysterious numbers and signs that he saw on the wall of the bedroom.

Kowalevski was born in 1850 in Moscow. At the age of eight, his father, a lieutenant general of artillery, retired and moved to the countryside. “We had to fix the whole house and paper all the rooms, but there were so many rooms that the paper was missing,” Sophie would later write. They ran out of paper for the children's room and used the pages of an Ostrogradski integral and differential calculus course purchased by their father in his youth to cover the walls.

“I remember spending many hours of my childhood in front of that mysterious wall, trying to decipher a few isolated sentences and trying to find the order in which the pages followed. Due to this long and daily contemplation, many of these formulas were etched in my memory; and the text, although still incomprehensible, left a deep mark on my brain.”

In this rural house, Sophie and her siblings received private teacher classes. By the time he was thirteen, he had shown an incredible gift for mathematics. “I was so attracted to mathematics that I began to neglect the rest of my studies,” he wrote.

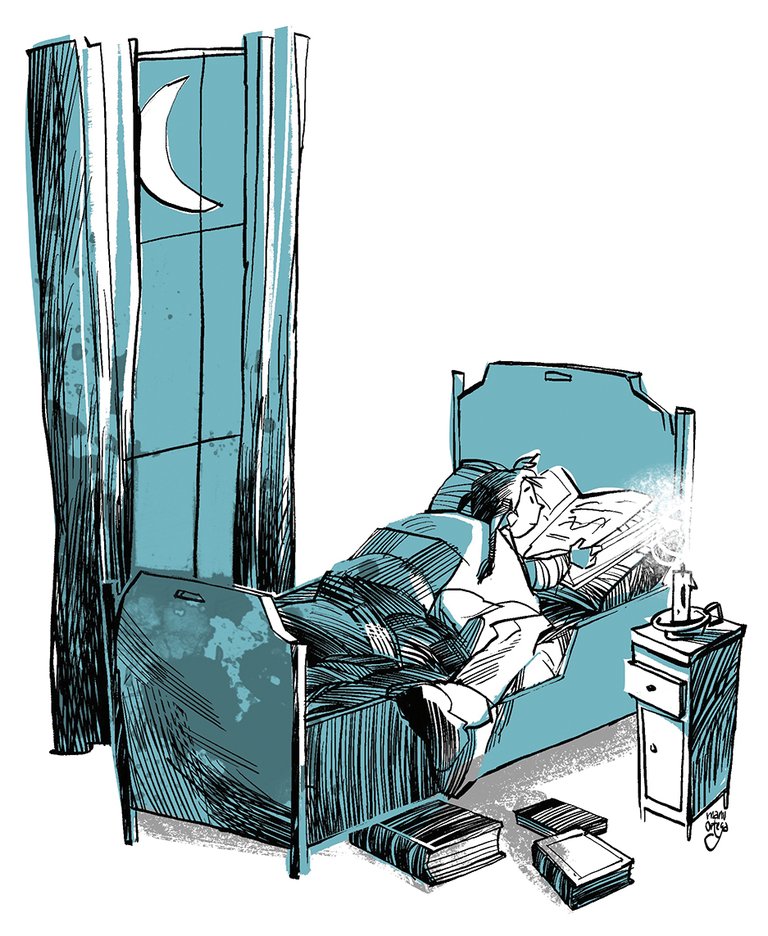

His father did not welcome this predilection for mathematics and, in order to provide an education that might be more suitable for a girl of that age and class, he interrupted his mathematics classes. However, Sophie's desire and insistence on continuing to study mathematics were not uncommon, and she continued to study on her own, obtaining books of mathematics and reading them at night while her family slept.

He knew he wanted to follow that path. But in Russia women were forbidden to go to university and could not leave the country without the consent of their father or husband. Since he had no hope of getting his father's, the only solution was to get married. Indeed, in nihilism, many young people were adopting the solution of conventional marriages. They were looking for a politically committed, liberal man who was only willing to marry in order to help women alleviate in some way this violent discrimination.

In Sophie’s case, this man was Vladimir Kowalevski, a progressive editor and translator (who translated Darwin into Russian). From then on, it would be Sophie Kowalevski.

After their marriage, in 1869, they both moved to Germany. Vladimir began studying paleontology in Thuringia and tried it at the University of Sophie Heidelberg. But he only managed to attend some schools as a listener. Even in Germany, women did not have the right to enrol in university.

The following year he moved to Berlin with the firm intention of requesting private lessons from the renowned mathematician Karl Weierstrass. Weierstrass, who was also opposed to women studying in college, was surprised by the young woman’s demand. But he didn't give her an immediate no, and he put her in a lot of trouble. When he saw their resolutions, he was amazed: they were not only correct, but also ingenious and original. He taught her for four years and helped her as much as possible in the future.

After four years, in 1874, Weierstrass asked the University of Göttingen to grant Kowalevski a doctoral degree. To this end, he presented three works by Kowalevski in those years, since, according to Weierstrasse, each of these works was enough to deserve the title. The first was about partial derivative equations, which has since become known as the Cauchy-Kovalevskaya theorem. The second is an investigation into Abelian functions. And the third, about the shape and stability of Saturn's rings.

Having obtained her doctorate, she returned to Russia with her husband. There, however, his degree was of no use to him and he was unable to work as a mathematician. He had a daughter and spent a few years away from mathematics.

But the worm lit up again, and he decided to go back abroad, to go back to mathematics. And that's when the best time of his life began.

At first he returned to Berlin, to Weierstrass, then to Paris, where he met some of the most famous mathematicians of the time and became a member of the Mathematical Society, and finally to Stockholm, where, thanks to the help of Mittag-Leffler, he was offered the opportunity to teach at the university. In the first year he had to work without pay, and then he was given an official teaching position for five years. She was the first woman to become a university professor in Europe.

In those years he did his most important work, known as the “Kowalevski Spinning Top”, on the rotation of solid bodies, which complemented the work begun by Euler and Lagrange. With this work he received the prestigious Bordin Prize from the Paris Academy of Sciences (1888) and later the Swedish Academy of Sciences. The work captivated the best mathematicians of the time for its elegance, depth and originality.

In 1889 he became a permanent professor in Stockholm. And that same year, he received a letter from one of the few mathematicians who had supported him from the beginning in Russia: “Our Academy of Sciences, with unprecedented innovation, has recognized you as a member. I am very happy that one of my most ardent and righteous wishes has been fulfilled. The Chebyshev.”

Two years later, when he was only 41 years old, a pneumonia became too bad for him. Before he died, he whispered these last words to his daughter: “Too much happiness.”

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian