The pain is in the brain

“I have pain. I get a headache quite often, but it's normal. In my family we have always had migraines, especially when the wind blows. It happens to my mother, too. It happened to my mother too. It's a family matter. The worst part is that the drugs don't do anything to me and I can't do anything. I am desperate.”

Pain is a complex sensory and emotional experience that may or may not be associated with tissue damage [4]. It's a signal from the nervous system that something may be wrong with the body. It can be acute or persistent and can be very different in intensity, duration and quality.

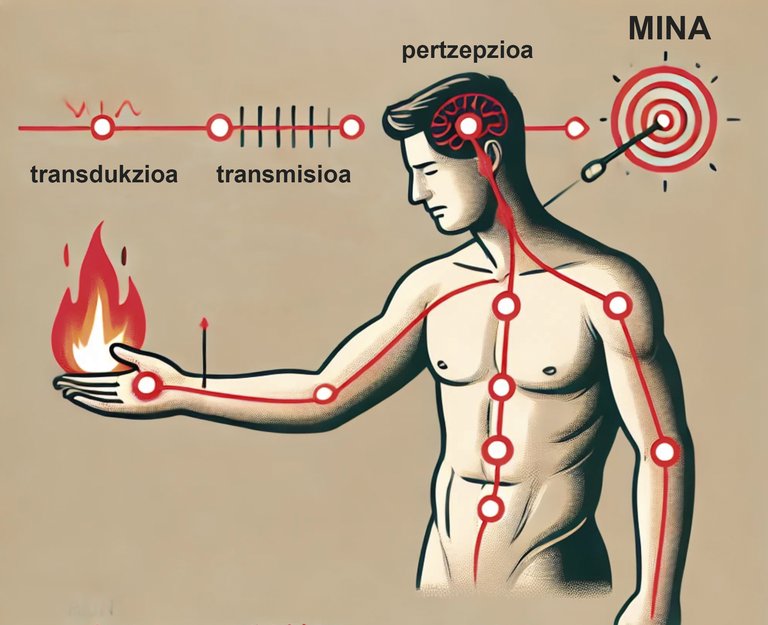

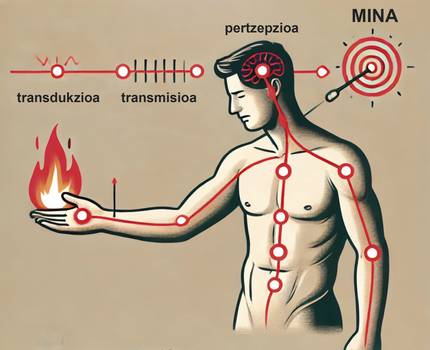

From a biological point of view, pain plays a key protective role as a warning signal, as it makes us react away from the source of the damage in order to prevent further damage [2]. A clear example, in which the protective function of pain is well visible, is the reaction to contact with an element that is too hot, such as a flame. By touching the hot element, our skin damage receptors* (also called “nociceptors”) are stimulated, as they detect heat as a harmful stimulus. Transduction then occurs, i.e., the noxious (or potentially noxious) stimulus is converted into electrical impulses in the neurons. These nociceptors then send a danger signal from the nerves to the spinal cord and an automatic withdrawal reflex is immediately generated. This indicates that the spinal cord has sent a response signal to the muscles of the hand before the mind fully processes the danger signal, so that we can move away from the heat source as quickly as possible. This risk signal also reaches the brain through a process called transmission. In it, information about what is happening is processed. On the one hand, the signal reaches the sensory cortex, which allows us to know where the painful stimulus is in the body. On the other hand, the signal reaches the limbic system, which modulates the emotional aspect of pain. It also reaches the prefrontal cortex, which allows us to interpret the meaning of pain and decide how to respond to it. Once all this information has been processed, the perception of pain is generated. After moving away from the source of the damage (in this case the flame), and as the tissue damage heals, the pain gradually calms until it disappears [11] [24].

However, in some cases, the sensation of pain does not go away despite the resolution of the initial cause and extends over time until it becomes pathological [23]. This persistent pain (also known as chronic pain) no longer plays a role of warning or protection and may adversely affect a person's quality of life. On the other hand, the persistence of pain after the initial tissue damage has healed indicates that the pain has become independent of physical damage. This is because the nervous system may be sensitized or “misinterprets” the signals, causing pain even without active injury.

Pain and harm are not the same

Two people with the same injury may experience different levels of pain intensity. What’s more, a person can feel pain even without any harm. Therefore, we can say that pain and tissue damage are not the same, although they are often related. Injury refers to physical injury or alteration of body tissues. Pain, however, is a subjective sensory and emotional experience, that is, it arises in response to stimuli considered harmful by the body [2] [5] [22].

As we have already said, there can be lesions without symptoms, that is, we can feel pain (continuously, sometimes) even without tissue damage. This happens, for example, to people suffering from a syndrome known as “phantom pain” [21]. It seems that the brain keeps a "map" of a body that no longer exists and continues to consider it painful, even if it is not damaged.

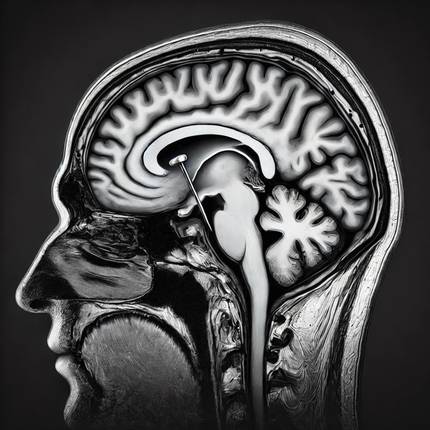

The opposite situation may also occur, i.e. there may be significant tissue damage without pain being felt. This happened to a 32-year-old boy from Illinois, USA named Dante Autullo. In 2012, Dante was building a cabin and accidentally fired a nail gun. He only noticed a slight wound; he healed easily and did not give it any importance. The next day, however, he felt dizzy and went to the hospital. During the brain resonance, it was observed that the nail entered the brain [16].

The pain is in the brain, and it's always real

Pain, although we feel it in different parts of the body (such as the skin or muscles), is always produced in the brain. The mind interprets the signs of damage and creates a feeling of pain. So even if there is sometimes no tissue damage, the pain is always real.

The presence of pain is a consequence of the activation of a complex neural network called the “pain matrix” [18] [19]. This matrix functions as an evaluation committee and is made up of different areas of the brain. For example, when a harmful or painful stimulus is detected, the somatosensory cortex is activated, allowing us to identify the location and intensity of pain. It also activates the frontal skin (involved in the emotional response to pain), as well as the prefrontal skin, which helps us to give meaning to the painful stimulus and to decide how we should respond to it. These areas work together to interpret the nociceptive (or hazard) signal and to continuously assess the level of safety. If the body thinks it is at risk, it triggers a feeling of pain.

We determine the balance between security and risk in a subjective way. We do this throughout our lives and it is conditioned by previous experiences, the education received, the culture and beliefs. This is how it is possible to understand why symptoms without stimuli sometimes appear. For example, when we see an image of spiders or lice, we can begin to feel an uncontrollable itch. The same can happen with the feeling of pain; sometimes the brain interprets things that are not real threats as threats. For example, when we relate wind and headache or weather changes to knee pain. All these relationships are based on beliefs created throughout life and determine the valuation that our mind makes. On the other hand, it has been shown that seeing the suffering of other people can activate areas related to pain in the observer's brain [20]. As David Butler and Lorimer Moseley, authors of Explain Pain, say, “pain will exist when the compelling evidence of risk is greater than the compelling evidence of safety” (8). In other words, pain exists when the person says he feels pain [17].

The pain is learned

The mind not only reacts to the world in which we live, but it constantly updates its own internal model of the world. We build this internal model based on past experiences and future expectations, and it helps us to predict what will happen. It seems that our mind unconsciously interprets reality in such a way as to ensure that our own beliefs are confirmed. In this way, we give more weight to the information that affirms our beliefs or previous hypotheses (and therefore gives order and meaning to our world). Instead, we reject or downplay the evidence against them. This is known as the “tendency to confirm” [13].

This phenomenon also occurs in political ideas or superstitions, as well as in the experience of pain. This tendency to confirm our beliefs can worsen the painful experience and reinforce negative beliefs about treatment or prognosis. For example, when a person predicts that the pain he or she will experience will be uncontrollable or worsening after certain treatments or due to external conditions (such as weather), he or she may unconsciously seek information to confirm these pessimistic beliefs. This phenomenon is known as the “nociceptive effect” [12].

It is important that people (both patients and health professionals) identify and challenge limiting or negative beliefs about pain so as not to aggravate the feeling of pain [9]. To do this, it is necessary to consider other opinions that deviate from one’s own perspective and seek information based on scientific evidence. There are a number of useful tools and treatments available to support patients, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, therapeutic exercise, and education in the field of pain neuroscience. This is the line in which the Units for the Active Combat of Pain are being created in different autonomous communities. The first was founded in Valladolid in 2019, and the second was launched in Vitoria in November 2023 [10]. In these units, physiotherapists, nurses and family doctors work together to treat patients with migraine, fibromyalgia and persistent back pain. The results obtained for better pain management are being very positive and encouraging [1] [3] [6][15].

The end: where the focus is, that’s where the focus is

As we have seen, our brain is not simply a passive receiver of stimuli, but an agent that constructs the perception of reality in a subjective way. This leads us to rethink how we should understand pain: beyond a simple physical reaction, pain is a subjective experience, shaped by our expectations, previous experiences and the context in which we find ourselves.

The activation of the “pain matrix” causes a sensation of pain that can be modulated. Emotions, stress, beliefs, expectations, and attention to pain, among other things, can affect how you feel pain. In some people, the “pain matrix” becomes hypersensitive, so pain can occur even without harmful stimuli, and sometimes becomes chronic. In Active Pain Management Units, where therapeutic exercises are carried out and scientific education on pain is offered, hope and useful tools are being offered to people suffering from persistent pain to help them improve their quality of life. Thank you for your work!

“If you change the components that

the mind uses to create

emotion, you can transform your emotional life.”

(Barrett, 2017)

The bibliography

[1] Aguirrezabal, I., Presented by Pérez de San Román, M. More about S., Cobos-Campos, R., et al. 2019. “Effectiveness of a primary care-based group educational intervention in the management of patients with migraine: A randomized controlled trial”. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 20, e155.

[2] Aguirrezabal, I., Assisted by Ramos, A. According to C., House in Urquiza, M. N. and Aguirre, I. It's about the M. 2024. “Physiopathology of pain”. The FMC. Continuing Medical Education in Primary Care, 31(8), 450-455.

[3] Areso-Bóveda, P. According to B., Images from Mambrillas-Varela, J., By García-Gómez, B., In Moscosa-Caves, J. I., I., I... By González-Lama, J., According to Arnaiz Rodríguez, E., et al. 2022. “Effectiveness of a group intervention using pain neuroscience education and exercise in women with fibromyalgia: A pragmatic controlled study in primary care”. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 23(1), 323.

[4] International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). 2022. Revised definition of pain.

[5] Baliki, M. According to N., & Apkarian, A. I'm talking about V. 2015. “Nociception, pain, negative moods, and behavior selection”. Neuron, 87(3), 474–491.

[6] The Compatriot-Cuadra, M. J., et al. 2021. “Effectiveness of a structured group intervention based on pain neuroscience education for patients with fibromyalgia in primary care: A multicentre randomized open-label controlled trial”. European Journal of Pain, 25(1), 1–13.

[7] Barrett, L. I'm talking about F. 2017. How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston.

[8] Butler, D. S. and Moseley, G. I'm talking about L. 2013. Description of Explain Pain (2. By the way, Ed. ). Noigroup Publications, Adelaide.

[9] Darlow, B. 2016. “The confluence of client, clinician and community”. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, 20, 53–61.

[10] The Basque Government. 2024. “The Osakidetza pain management unit has treated 768 patients in the first year.”

[11] Ferrándiz, M. 2006. [Physiopathology of pain]. Catalan Society of Anesthesiology, Resuscitation and Therapy of Pain.

[12] Ferreres, J., Baños, J.-E. and Farré, M. 2004. “Nocebo effect: the other side of the placebo”. Clinical Medicine, 122(20), 511–516.

[13] Friston, K. 2005. “A theory of cortical responses.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 360(1456), 815–836.

[14] Grünenthal Foundation & Observatory of Pain of the University of Cadiz. 2022. [Chronical pain barometer in Spain 2022]. The Grünenthal Foundation.

[15] Galán-Martín, M. I'm talking about A., Images from Montero-Cuadrado, F., Images from Lluch-Girbés, E., Other works by Coca-López, M. According to C., The Mayo Iscar, A., and the Cuesta-Vargas, A. 2019. “Pain neuroscience education and physical exercise for patients with chronic spinal pain in primary healthcare: A randomised trial protocol”. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 20(1), 505.

[16] Main, F. 2012. “‘Unfreaking believable’: fiance says Orland man recovering from nail in his brain.” The Chicago Sun-Times.

[17] McCaffery, M. 1979. Nursing Management of the Patient with Pain (2. By the way, Ed. ). Lippincott, Philadelphia.

[18] Melzack, R. 1999. “From the gate to the neuromatrix.” Pain, 82(6), S121–S126.

[19] Moseley, G. I'm talking about L. 2003. “A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain.” Manual Therapy, 8(3), 130–140.

[20] Osborn, J., and Derbyshire, S. I'm talking about W. According to G. 2010. “Pain sensation evoked by observing injury in others.” Pain, 148(2), 268–274.

[21] Villaseñor Moreno, J. According to C., By Escobar Reyes, V. More about H., Assisted by Sánchez Ortiz, Á. Oh, and Quintero Gomez, I. According to J. 2014. “Phantom Member Pain: Pathophysiology and Treatment”. Journal of Medical Specialties, 19(1), 62–68.

[22] Wall, P. According to D. 1986. “The relationship of perceived pain to afferent nerve impulses”. Trends in Neurosciences, 9(12), 435–439.

[23] Woolf, C. According to J. 2011. “The central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain”. Pain, 152(3), S2– S15.

[24] Zegarra, J. I'm talking about W. 2007. “Pathophysiological bases of grief.” Peruvian Medical Act, 24(2), 35-38.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian