Visit to Cambridge Professor

2009/06/01 Etxebeste Aduriz, Egoitz - Elhuyar Zientzia Iturria: Elhuyar aldizkaria

At the door of Isaac's office, Edmond did not know what he expected very well. Letters were never written and were seen once in London. Moreover, Edmond's relationship with Mr. Hooke was known, and it could not be said that Isaac was very interested in that man. But Edmond sought an answer and hoped that Professor Newton would give him some explanation.

The visit may be the greatest contribution of the English astronomer Edmond Halley to science, although his name has come to us through the famous comet. He did not find it, but he realized that the comet he had seen in 1682 was the same as he had seen others in 1456, 1531 and 1607. He didn't even give him a name. Halley did not become comet until 1758, when Edmond had died 16 years.

He was ship captain, cartographer, professor of geometry at Oxford University and royal astronomer. He invented the diving bell, wrote about magnetism and tides, the movements of the planets and the effects of opium.

It was precisely the movements of the planets that led to Halley Newton, the movements of the planets and the conversations held for a dinner a few months earlier. In that inaugural dinner of 1684, Halley composed with two other illustrious characters of the time: Robert Hooke, a man who first described the cell, and Christopher Wren, an astronomer before the prestigious architect, author of St Paul's Cathedral in London.

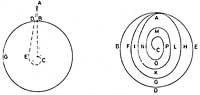

At dinner came the theme of the trajectory of the planets around the Sun. By this time they knew it was elliptical, but they didn't know why. There were also suspicions that the key was in the square of the distance of the planets to the Sun, but they were not able to prove it. Thus, Wren challenged two other people: A book worth 40 shillings (a couple of weeks salary of the time) for those who will find a solution in the next two months.

Hook was famous for taking on the ideas of others, and it could not be said that humility was his greatest virtue. He immediately said he had found the solution. But he decided to keep it hidden for a while, so that everyone who tried to find the solution would value the value of discovery more.

Two months passed and Hooke remained silent. Halley continued to work on finding the solution. Finally he went to Cambridge and it occurred to him to ask for help from Professor Isaac Newton. And he was there, without appointment and without knowing very well what Newton expected before one of the most important encounters in the history of science.

Fortunately for Halley, Newton gladly welcomed the astronomer's visit. Newton's trusted friend, Abraham DeMoivre, told us what happened there. After discussing eleven questions, Halley asked him at the end what curve the planets would do if the pull force between the Sun and the planets was supposed to be inverse to the square of their distance.

Sir Isaac Newton did not have to think much, he replied immediately: the ellipse. The young Halley, delighted and surprised, asked him how he knew. "Because I calculated it," Newton's answer. Dr. Halley asked him to show those calculations. Newton began to search through his papers, and found no such calculations in vain. In the end, he promised Halley that he would do them again and send them to London.

He had to wait three months, but Newton did not forget it. In those three months he wrote a 9-page work on this subject: By Motu Corporum in Gyrum . Halley immediately understood the value of the work and saw the need to publish it.

When De Motu was working to convince Newton to publish his work, because Newton never gave much importance to publication, in January 1685, Newton wrote: "Since I'm now on this topic, I'd like anything to get to the bottom before publishing."

And in two years he published Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Matematica, or the famous work known as Principia, the greatest scientific work ever written. "Never has an individual approached the gods so much," Halley acknowledged. In addition to mathematically explaining the orbits of the bodies of the Universe, he identified the force that these bodies set in motion: gravity. In this work Newton collected the three laws of motion and the law of universal gravitation.

But Halley's efforts were also fundamental in the publication of Principia. For example, when the work was about to end, he entered an intense debate with Hooke. The core of the debate was precisely who demonstrated the reverse square law before. As a result of this debate, Newton refused to publish the third decisive volume of his work. Halley's diplomatic mediation and high doses of blurring were necessary to remove Newton's third volume.

And it was not the only problem. Although the Royal Society initially pledged to publish its work, it eventually withdrew due to economic difficulties. He had just suffered a great economic defeat, with his book The History of Fishes, and they suspected that no book on mathematical principles would be very successful.

In the end, Halley himself paid, despite the fact that the money was not left over, his publication. Newton, as usual, did not put rockets. In addition, he had just worked at the Halley Royal Society at the time and was told that he would not be able to pay the promised salary. He was paid with copies of The History of Fishes instead of money.

Gai honi buruzko eduki gehiago

Elhuyarrek garatutako teknologia