Brothers Herschel, from music to stars

He arrived in England nineteen years old and without money. It was 1757, the French had taken Hanover and left there. Wilhelm Herschel was a musician, like his father and almost the whole family. He played the chelo, the oboe and the clavecino, and composed it. He advanced teaching music and playing in orchestra in England.

For Caroline the blow was hard. He was then seven years old and admired his brother. And during his years of absence, admiration only grew. In England, Wilhelm became William, and ten years later, Bath was responsible for the city's concerts, organist and choir director.

Meanwhile, in Hanover, Caroline was not much more than a housekeeper. At the age of five he had the margin and with the eleven the typhus, he was small - he did not reach the meter and half - by diseases, leaving his face full of marks. As his father once told him that he was “neither beautiful nor rich,” he could have no hope of marriage and had to settle for caring for his older parents.

William was concerned about his sister's situation and invited him to live with her in England. Caroline arrived in Bath in 1772. His brother gave him singing lessons and in his concerts he put him as a solo singer. Caroline, an excellent singer with great success.

But William not only taught music to his sister. In fact, William was a person with great curiosity and studied mathematics, optics, astronomy... in free time with ingestion of machines. In the breakfasts she told her sister what she learned from the books the night before. And he followed with great interest the lessons of his brother.

William was especially fond of astronomy. He spent hours staring at the stars, analyzing the sky, and was fascinated by the Moon. He said he would live there. Music students narrated how he often stopped school and pulled them out to see the Moon.

William needed a telescope. But the quality of those who could pay was very low and only got frustration. In the end he decided to do it.

William became a great telescope manufacturer and had a great assistant, Caroline, who was also able to polish lenses and mount telescopes. He always accompanied him. "Once I had to give the food to my mouth," Caroline wrote later, "I was finishing a two-meter mirror and didn't take my hands over it for sixteen hours." And when my brother was on the telescope, he would write down everything he described.

William saw mountains and forests on the Moon. Astronomers knew that by then the moon had no atmosphere and that it was impossible. But William was convinced that there were living beings on the Moon and on other planets and stars. It was not a good start.

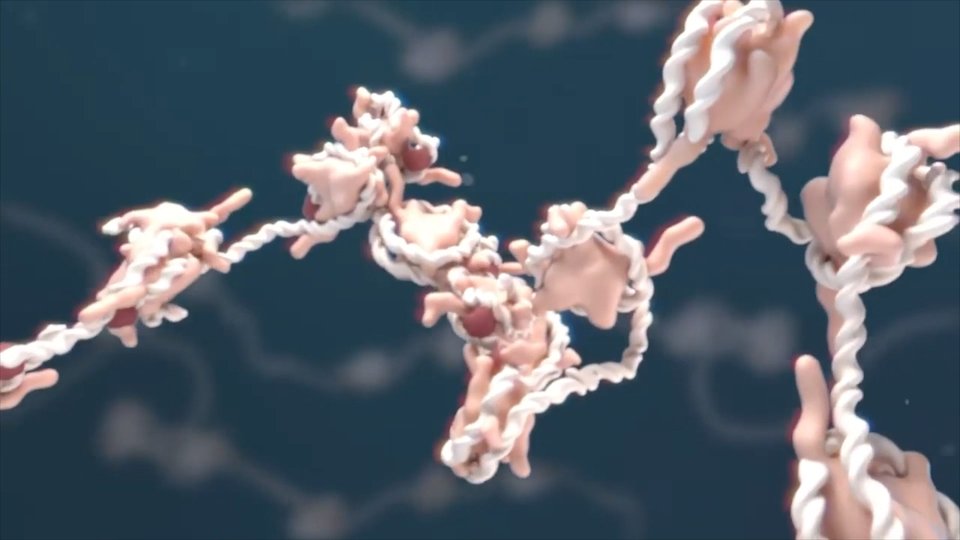

But the herscheldarras did much more. For example, they observed pairs of stars. It was believed that these stars were aligned from Earth. William began to observe all the pairs of stars in the sky. He found about 800 pairs and, after 25 years of tracking the movement of these stars, he actually showed that they were physically contiguous stars that rotate each other.

In 1781, from the garden of his house observing his pairs of stars with a telescope, a discoidal object caught his attention. At first he thought he was a comet. But he followed him and discovered what his movement was like. It was a planet of the Solar System!

He suddenly became the world's most famous astronomer. For thousands of years no one found a planet. He wanted to call the planet Georgium sidus, star of George in homage to the king of England. But in Europe they did not accept it and for a time it was called Herschel. Finally it was decided to continue with the mythological names: They put Uranus on him.

That same year he was a member of the Royal Society and the following year George III named him Astronomer of the King and paid him the salary. Thus, the herscheldarras abandoned music to devote themselves fully to astronomy.

William gave his sister a telescope to make his observations. But Caroline couldn't find the time she wanted. With William's projects he worked quite a lot. In addition to assisting in the observations, he performed the long calculations necessary to obtain the results of what was observed.

However, in 1786 he found a comet and the news spread quickly: "The first comet a woman finds." As collaborators of William, the king managed to put a small salary in 1787.

The following year, William married a rich widow. Caroline did not get the change very well. He did not like William's wife. He later changed his mind. And also, since William was with his wife, he had more time to make his observations. He discovered seven other comets, stars and nebulae.

William also continued to make telescopes. They were the best in the world. And the largest in the world, 12 m long. In August 1789, in his first observation with this telescope, he found a new moon of Saturn: Mimas. And one month for another: Enceladus.

He had previously discovered the first two moons of Uranus, Titania and Oberon. In addition, it was the first variable star observer and was the asteroid name itself. With the help of her sister she catalogued 90,000 stars and 2,500 nebulae. And he announced that nebulae are made up of stars, stars and, perhaps, other galaxies like ours. Thanks to the telescopes and the work of the Herschel, the universe soared. And the solar system was just a small group in the giant universe.

William's life lasted the time it took Uranus to turn around the Sun: He died at 84 in 1822. Caroline returned to Hanover, but did not abandon astronomy. Among other things, he continued to corroborate William's discoveries and published his catalogue of nebulae. In 1828 the Royal Astronomical Society awarded him the gold medal for this work. And in 1835 he and Mary Somerville were honorary members of this association. They were the first women to achieve this distinction.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian