Chestnut for cold winter

1999/12/01 Kortabarria Olabarria, Beñardo - Elhuyar Zientzia Iturria: Elhuyar aldizkaria

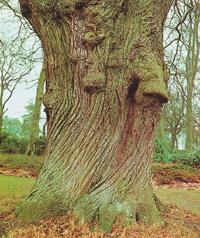

It is not known to what extent what the elderly count is a distorted memory of the sweet youth and its reality. In any case, the stories seem closer to reality than to the distortion of memories. To realize this, just spend a few hours on the mountain. Both old chestnuts and those planted 20-25 years ago can be affected by diseases, with branches without leaves, uninhabited from autumn to autumn. Understanding the declining state of chestnut trees can also mean that there is no updated data. That is, in 1950 the chestnuts in Hego Euskal Herria covered 14,530 hectares of land, from there there there is no data. Sign of loss of importance in chestnuts. In the forests of Euskal Herria, between oak, beech and pine forests, you can still see chestnuts, both old and young, but less and less, more sick.

In the case of chestnut trees we have to talk about evils and not of evil, since those that cause the most damage and do are mainly two: ink and chancro. Ink and chancro have caused the loss of many chestnut trees, especially in the last two decades of this century, since disease attacks must add abandonment. In fact, at one time it became more important than today, they were more careful.

Ink, a disease that has been expanding

The first news about ink disease in Spain dates back to 1726, in the Sierra de Gredos. From then until the end of the last century the disease was not known. In fact, in 1871 and 1872 it appeared on the Basque coast, between Ondarroa and Lekeitio. Soon after the disease spread to Galicia. Among them, Asturias, Cantabria, Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and the Baztan valley. The ink also went inland, mentioning Avila and the Sierra de Gredos. According to the documents of the time, it caused significant damage.

Today, the peninsular north is under the influence of ink, it also influences the interior, as in Salamanca, and does not seem to affect the south and north of Africa. However, it seems that ink disease is not spreading, it has somehow stopped.

The ink is responsible for the fungus Ficomiceto Oomical (Phytophtora cinnamoni). This fungus, which normally inhabits the organic matter of the soil, is introduced into the tissues of the tree when its ramifications capture the remains of chestnut. Therefore, they become parasites and cause an infection. If the infection traps the smallest clays of chestnut, the tree will die slowly, as the main lump will be able to create other small ones and thus survive, while if the infection starts near the trunk, chestnut will not last long, as it will not be able to create new clays.

When the ink captures the branches of chestnut begin to dry, the leaves are yellowish and fall early, the chestnuts are also scarcer. Before dying definitively, usually before dying, chestnut gives a lot of worthless chestnuts. The ultimate test to find out if the ink has caught the tree or not is to look at the bottom of the tree trunk; if it has a black throat spot… bad!. This stain is a consequence of the reaction of the tree, the chestnut, against the parasite.

The ink spreads very quickly, since the contact between the tree fusts, the transport of the branches of the fungus when moving the soil by the animals or people, the transport of the spores through the water… Not only that, the fungus is able to create sexual spores —oospores—, asexuals —zoospores— and chlamydospores, which have been found in the winter.

When the disease has just begun, the most effective treatment is the chemical. However, its implementation at mountain level is difficult because it can only be used with specific fungicides. However, in nurseries and young plantations it is possible to use them. The treatment of old chestnuts is even more complicated. Around the trunk opens a hole of half a meter, until the main lumps appear and if possible without causing wounds. Once the hole is made, the stems that are exposed in the soil are removed and a chemical treatment is performed. If there is no risk of rain, cover the hole immediately. In view of the difficulty of taking one or another measure, studies were initiated to obtain resistant to chestnut disease. In 1925 the first chestnut trees of this type were obtained in Galicia. To obtain resistant to brown ink two techniques are used, hybridization and exploration. In the case of hybridization, the chestnuts here intersect with those from Asia, resistant to ink. However, Asian chestnuts bear low quality fruits and several crosses are necessary until they get a chestnut with fruits similar to those of here. The exploration is limited to locating chestnuts that have naturally resisted the ink.

Although the technique is known, obtaining resistant chestnut is a medium and long term work. However, this is the only solution that has been found so far to combat ink.

Import Chancro

Unlike ink disease, chancro seems to come from Asia. However, the first news about the damage of the disease comes from the United States (USA) in 1904. In fact, in Asian chestnut species the influence of chancre was not very important, as they had some resistance, while US chestnuts were not able to fight the disease. Therefore, entry into the US and the Chancros caused in a very short time enormous damage to the chestnut population. He joined Europe in 1938, for the first time in the Italian Liguria, subsequently extending to Switzerland, France and Spain.

The fungus Ascomiceto Pirenial (Cryphonectria parasitica) is responsible for chestnut skin chancre. The chancre, especially in the younger branches of the trees and in the soft barks, is later perceived the symptoms of chancre in the older parts of chestnut, the more wrinkled. The skin of the trunks of the fallen chestnut trees on the chancre becomes reddened, narrower and superficial cracks can form. Under the skin are formed white ramifications in fan form, drying the cups of the chestnut as the wrinkled brownish leaves that do not fall from the branches. In turn, twigs and chancro fruits are created in the affected areas.

The fungus normally penetrates through the superficial wounds of the trees. For example, hail can easily hurt chestnut trees. Although the entry of the disease is injured, the infection can spread through these wounds or the cracks of the skin, or through the insertions of the young branches. The disease can attack all the upper parts of chestnut, although especially on the skin, and develops in the subcutaneous part that grows year after year. When the fungus enters, the chestnut fight begins to fight it and suffers various reactions. If the fight is won by the fungus, in the chestnut appear the symptoms mentioned above. As in the case of ink, the most suitable solution to fight chancro disease is to develop resistant types of chestnut. In the extension of the ink, although a certain paralysis is observed, the chancro is constantly expanding, especially in the Basque Country and nearby provinces. As a result of the losses resulting from this disease, collaboration projects are currently being developed in European countries with similar problems such as Italy, Spain and Portugal. Thanks to this collaboration and the biological war, it seems that in the coming years chestnut trees can be obtained able to cope with the effects of chancro.

Although most of the chestnuts that today survive in the mountains are not their own or cultivated, it seems that chestnut is also a tree here, therefore native. In fact, chestnut sediments from 10,000 years ago (Ekain de Deba) have been found in the Basque Country and 40,000 years ago. Obviously, then no one cultivated them. This does not mean that many of the chestnuts that have been planted later are not of Asian origin, but that chestnut is from here.

However, for the chestnuts here and abroad these are not the best times, although in the Barranca de Navarra is working on the recovery of chestnuts. It is not many years that chestnuts were important in winter life. The chestnuts collected in autumn were kept to spend the best possible winter, or they were taken to the market to sell them and to face another need with the money that was taken in exchange... they were fundamental for the economy of many farmhouses.

And is that currently chestnuts do not have much estimate. They can be bought in hypermarkets or in small shops close to home, most imported and at affordable prices. The premises, the mountain ones, are hardly sold. At most, they gather to work at home; the rest are for retirees who have no homework or children who go to the late night mountain. Chestnuts and chestnuts are of no temporal importance.

Gai honi buruzko eduki gehiago

Elhuyarrek garatutako teknologia