Jon-Kar Zubieta: "Psychiatric illness is a disproportionate form of normal behavior"

We know that the prevalence of deep depression has not changed too much. A hundred years ago the prevalence was first reviewed, and since then there are no big differences. Yes, detection has changed a lot. 30-40 years ago, only those with obvious and serious symptoms received medical attention and treatment. It should also be noted that the medications of the time had more and worse side effects than the current ones, so it is normal to treat only the most serious cases with drugs.

In addition, today we all have more epidemiological data and information about psychiatric diseases and especially about depression, so the stigma is lower. Before, however, many people were stigmatized from attending the doctor. In fact, women, because they are clearer than men, usually go to the doctor more easily because of these problems. In the case of men, in general, stigma is more worrying than that of women, and probably as an indirect consequence, so they tend to abuse harmful substances.

Well, I don't think stress agents are more than before, but they are others. For example, now finding food is easier than 150 years ago, wars are not like 200 years ago... But there are other types of stress agents: there is a lot of information, and that can generate stress to some, or driving is stressful...

However, if you look at the most serious stress, it has not changed as much, as the death of the wife or husband, or the facts that deeply affect the person, that have not changed. In fact, mortality has decreased, so we cannot say that we have more stress than before. Maybe the current stressors last longer and we live faster and that's the bad thing. However, the main stressors have not increased; in any case, they may have decreased and this has.

Yes, we are now aware that these diseases are not a matter of imagination, but of neurobiology. And while we haven't made enough progress to know all the answers yet, and we have a lot to investigate, we're moving forward. How long has it been since the first heart transplant? Forty years. And today, heart, lung, liver, and kidney transplants are common operations.

But, of course, they are simple organs with respect to the brain. That is perhaps the new limit. We must deepen in neuroscience to overcome the barrier and obtain better treatments for people through research with people and animals.

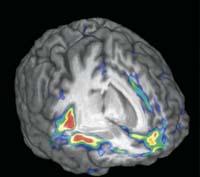

That is. We use PET, RMNf and other anatomical techniques or circuits. Thanks to them we can see what happens in cells, live in people. In fact, we already have animal research data and are now working with people.

The aim is to combine genetic data, specifically those related to genetic polymorphisms, with the influence of these variations on neural circuits and, of course, on their behavior. It is not enough to study the genes, the behavior is very complex and can change for one or another nucleus, for connections… and it is important to know what are the biological bases of this behavior to relate genetics to the science of behavior, to build a systematic neurobiology of psychiatric and neurological problems.

No doubt. Genetics have advanced much more than expected in a very short time. It should be noted that five years ago, when the first human genome study was done, it cost millions and millions of dollars; today, for 800 dollars, and many people at once. That is to say, techniques have been much cheaper and much simplified, and thanks to it, now are many scientists who are researching and publishing results in this field. Progress is being exponential.

Indeed. It is called epigenetics. Previously it was thought that the interaction between genes and the environment was unidirectional: first there was the gene, then the alteration or change in neurological activity and finally the behavior. Now we know that it is not so simple. In fact, behavior and environment influence brain cell systems and gene activity in an epigenetic way. It is therefore a two-way interaction. The environment changes the brain and changes the activity of genes, not genes, but their expression.

Knowing this, we now do the research differently. Now, for example, we look for genes related to ease of having a neurological or psychiatric problem. And as you know the genes, the next step is to investigate their regulation.

In animals, yes, RNA is being investigated to modify the activity of certain genes and thus influence behavior. In people, however, we are still in the previous step, at the cellular level. And there we are; the more we know about neurobiological systems related to psychiatric diseases, the more possibilities we have to get more and better treatments. For example, a new drug has recently been taken to treat schizophrenia based on glutamatergic receptors. The deepening knowledge of the glutamatergic system has caused, in this case, the synthesis of an effective drug that until now did not exist. And that's just an example. Without knowing what happens in neurobiological systems, it is very difficult to get right with treatments.

They go at slightly different rhythms. I am a psychiatrist and somehow psychiatry deals with more complex problems. Neurology has always been responsible for the search for the lesion, which normally occurs due to vascular problems, which explains the alteration of behavior. Psychiatry is more difficult, studies more complex behaviors, since they are related to emotional function, cognition... And the biological basis of these behaviors is more complex than in neurology. There are several neural areas, several circuits, genes that interact with proteins in these circuits... all of them, and that is why it is more difficult. However, in the last ten years we have made tremendous progress, a breakthrough that is due to collaboration in genetics, neurobiology and behavioral analysis.

Psychotherapy is another way to address the same problem. In English it is called top-down regulation, i.e. descending regulation. The problem is that we have some areas related to brain, skin, cognition and regulation of emotions, such as prefrontal cortex. These brain areas modulate the function of other more interior areas such as tonsils, heel, or nucleus accumbens, which respond to the environment, such as stress.

This is the downward regulation and it is believed that psychotherapy is influencing. Psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, can increase neuronal control in emotional function. And it is true that to a certain extent we have seen the influence of psychotherapy with the technique RMNf.

Another way to modify the functions is to botton-up, from bottom to top: change the functions of nervous neural systems with drugs, and thus modify the behavior.

Normally, both in depression and other psychiatric diseases, the best treatment is dual. However, in some cases only enough psychotherapy or only medicines. And other times they do nothing, neither one nor the other, nor the two together. That's why I think we can't limit ourselves to a single treatment, but we have to use all the options.

It is not always easy to distinguish the border, as there are great differences between people. The problem is to differentiate a variety of pathology and normality. For example, grief after the death of a person you want is healthy and necessary, but it becomes pathological if it is too long or prevents the person's normal behavior. This obstruction defines the disease. It's like a liver that doesn't work all right. If it doesn't give you any problems, aren't you going to do anything? But when it works badly, it causes jaundice and gives physical problems, then it is a disease. The same goes for psychiatric diseases. In fact, psychiatric illness is a disproportionate form of normal behavior.

No, look: I really like to compare with physical pain. Physical pain is necessary, because if you are unable to feel pain, you risk incredible physical problems. For example, if you put your hand in the fire and feel no pain, you will burn. In fact, pain tells you that you have to remove your hand, that is, pain helps you interact with the environment. As important as physical pain is emotional pain. If you have no emotion, you are autistic. Yes, as with physical pain, when it becomes chronic and hinders the person's normal behavior, it becomes a problem. There is the question.

Yes, and it is very interesting. The placebo effect is almost disease. It is the ability our brain has to respond to a suggestion that responds to a suggestion in which you are taking something that will benefit you, so the neural responses it gives are really useful to heal and recover.

The neural systems involved in the placebo effect are contrary to vulnerability. They are related to endurance, resilience. In reality, it is a way to recover; contrary to what we investigated. That's why we started researching the placebo effect.

We investigated especially in the field of pain, where models have been investigated more than in other areas, but also in depression and other diseases is looking at the placebo effect.

For example, from research we have concluded that the function of these nervous systems is to interact and respond to the environment. When the environment is beneficial, there is a therapeutic medium and treatment is being received, some changes occur that cause recovery of function. And those changes produce themselves, even if the treatment is not effective. That is the placebo effect.

It is true that there is a huge difference from one person to another. In some people, when they think they are receiving treatment, the response of these neural systems is enormous, in others it is much smaller and sometimes the opposite occurs. That is, they suffer the noebo effect: in principle treatment has no effect, but the response that the belief of being in treatment produces in neural systems, instead of benefiting, is counterproductive.

Why does that happen? We do not know. We are now investigating the genetic aspect of this process, the differences between people, whether women and men respond differently... And, for example, we have seen that there are differences by sex.

No, optimism has nothing to do with the placebo effect. We look at that question. There are scales of optimism, and we have also prepared some, and we use them to know if any scale served to predict whether someone would have a greater or lesser placebo effect. No value.

The placebo effect is more complex and related to the environment. In fact, there are four levels of functioning and, due to its complexity, it is not surprising that there are differences between people. These levels are the interpretation of the environment, the neuronal system that responds, whether or not the system is healthy and the genes that modulate its functioning.

On the other hand, it is very difficult to know why a person is optimistic or pessimistic. Why is it optimistic? Some are optimistic because they have a very good life, but others with a bad life are also optimistic. That is, there are many reasons for someone to be optimistic: because things have gone well or because he doesn't mind going bad, or because he has genes that help him to be optimistic.

Yes, but measuring the genetic effect on optimism or pessimism is extremely difficult. In such complex characteristics many genes intervene and each influences to a different extent. That is why it is so difficult to investigate.

No, no, a person may have much faith in God, but none in the doctor who has treated or treated him. The only thing we saw that was related to the placebo effect was anxiety: people with much anxiety have less placebo effect. It's logical, of course, if you're getting treatment and you're very anxious and worried about treatment, it's normal to decrease the effect.

(Laugh) We have no danger of running out of research.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian