Moderating time

2004/12/30 Galarraga Aiestaran, Ana - Elhuyar Zientzia

In fact, it is known that time does not pass the same, although time is the same in both cases. Such a subjective perception of time makes the need for an objective and concrete way of measuring time more necessary.

The first system to measure time has been the alternation between night and day. As for lunar periods, the old men and women had the opportunity to measure and designate longer periods of time. In the remains of 20,000 years ago, archaeologists have found bones and sticks marked and perforated by man. These marks appear to indicate the phases of the moon.

In those times, men and women lived united with nature. They fed on the animals they hunted and the fruits they collected, and when in one place they began to reduce the food they went to another place. They knew nature well, so they knew where the Sun was going, what the phases of the Moon were, and how the planets moved.

Later, in the Neolithic, man became a farmer, which radically changed his way of life. He became sedentary and lived from the plants and animals growing. Then they also needed to measure the passage of time; the Sun and the Moon were their clock and the positions they took in the sky indicated when it was the best time to sow or harvest.

They saw that in nature the Sun prevailed, so they believed it was almighty and have endured to this day the reflection of the customs and rites created by that admiration. Christmas is a clear example of this. It is celebrated in the winter solstice and is then when it begins to germinate under the soil. The peasants fed the newborn Sol with fire and sacrifices. At the other end, the bonfires that turn on the eve of San Juan are the echo of the summer solstice, of the times when the strength and victory of the Sun was celebrated.

Sun and shade

To carry out their activities, farmers were sufficiently careful to observe nature. The sacred feasts and days associated with these activities corresponded to religious men, who had to be exact. To them, therefore, calendars and advances in astronomy are due. In fact, that science depended on them, which was often used to dominate citizens. How did they not respect the one who knew that the day was going to turn into night? Knowing when the eclipse was going to happen would undoubtedly give a great power.

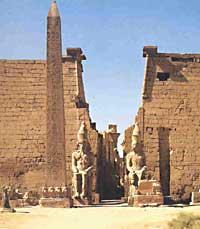

It was then that the first watches were born and most were based on the shadow that occurs when touching the Sun at a given point. That is, they were sundials. Solar watches have been used in all civilizations, such as China, India, Egypt and Greece. We still observe this type of clocks on the walls of several churches, arriving to us remains of older times.

For example, the obelisks raised by the Egyptians about 5,500 years ago remain standing in more than one place. The shade projected by the obelisk indicated to the population when it was noon and what were the longest and shortest days of the year. Shortly afterwards, some marks were made around the obelisks to divide the day into more parts.

And the first sundial marking the hours, a. C. C. VIII. It was invented in the twentieth century. Thanks to this tool, the day was divided into ten parts and had two other marks to determine when the sunrise and sunset were. This apparatus consisted of two rods, one of them base, which was placed horizontally on the ground and the other was placed crossed in one of its ends. One of the ends of the upper rod gave the shade at the base and in that base were marked the hours according to the shade. The device was placed in the east direction in the mornings and at noon it was turning to spend the afternoon hours.

a.C. III. In the nineteenth century, astronomer Babylonian Berosus built a hemispheric solar clock. Inside a cube leaves a hemispherical hole and on its top places a rod. In the hole there were marked hours, depending on the time of the year, and the shadow that gave the rod indicated the time it was. From that clock the hemicycle was invented, which was the XIV. It was used until the twentieth century. Therefore, the solar watches that have been created later are their initial variants. In any case, the changes have been made to achieve greater precision.

Water, sand and fire

In the sun, the shadow that projects any object is sufficient to measure the passage of time. But what to do at night? This question was answered long ago. For example, the ancient Egyptians used clepsidras. The first clepsidras were a pot of mud, to a certain point full of water, with a hole in the background. The water came out of the hole at a constant speed, so they could calculate the passage of time as the container was emptied. Thus, they indicated the time with the marks made on board.

In the Athenian courts, the water clocks were used to know the distance of each speaker and in Rome for night watch shifts.

IX. In the nineteenth century, Chinese scientist and official Su Song invented an astronomical clock with very complex water. The clock was a tower of about six meters. On the high it had a water tank from which the water was poured, hitting the blades of a wheel. The wheel moved several mechanisms through which the clock spent hours, expressed with gong sounds and drum. It also moved a celestial sphere with stars and constellations. That watch was quite accurate, as it only had an error of two minutes per day.

Sand watches work in a similar way to Klepsidd, but replacing water with sand. The sand watches consist of two glass containers, connected to each other. The sand is located in one of them and passes to another at constant speed. When passing the last grain of sand you have to turn the clock.

Depending on the size of the watch and the quantity of sand, the sand watches serve to indicate minutes or hours. Apparently, the sand clock that Charlemagne had was so big that it was only necessary to fly every 12 hours.

However, although clepsidras and sand clocks are very useful for measuring time at night, perhaps the most suitable for the night are candles. In addition to illuminating the night, candles serve to measure time. Previously, marks were made in the wax and it was known at what time the wax had arrived.

Mechanical watches and mechanical watches

In the years 1267-1277 the books of knowledge on astronomy of Alfonso X the Wise appear in the writings the first vestiges of mechanical watches. The engine of these watches was moving by the weights. At the end of a string a weight was placed, which was filled with a rotating drum tip and wound around it. The weight, by the force of gravity, came down and the string, when it dropped, dragged the drum.

XV. In the twentieth century there were two inventions: the motor of docks and the connoisseur of Leonardo da Vinci. In 1505, the German Peter Henlei managed to make small watches with spring motor. They were called ‘sack watches’ because they wore them inside a bag. They played every hour and lasted 40 hours.

Soon extended the custom of placing wall clocks in the houses of the rich. XVII. In the eighteenth century the pendulum clock revolutionized. It was invented by the Dutch scientist Christian Huygens, very precise and allowing to count seconds. However, the idea of using the pendulum in watches was not theirs; in 1636 Galileo Galilei proposed to do so, but by then it was already aged and blinded and could not materialize the idea.

XVII. At the end of the twentieth century the watches called ‘onion’ were fashionable, which the wealthy men wore in the pocket of the vest and the women hung from the waist. Then, the watches were luxury objects, really expensive, and only those of high level could have and use watches.

Watches within reach of all

They say that the first wristwatch was made at the request of the queen of Naples in 1812. But it was at the request of a woman, but was mostly used by men. For example, XX. At the beginning of the twentieth century they were used by the high positions of World War I, which contributed to the expansion of wristwatches.

In 1929, American watchmaker Warren Albin Marrisson invented the quartz watch. The error of that watch was 30-0.3 seconds per year, that is, it was the most accurate clock of all time. For its manufacture it used quartz crystals, whose vibration is constant and that, converted into electric current, moves with precision the engine of the clock. Currently, quartz watches are still used.

In 1957 the first electric watches appeared. The energy supplied by a small battery is the one that moves the engine of these watches and are very accurate. However, the most accurate are atomic watches. These watches are based on the vibration of the cesium atom and have only one error of a second of 30,000 years. Although time has been so accurately measured, scientists are not believed to have stopped investigating, they are now working with watches based on the characteristics of hydrogen. The error of this watch would be a second of 3 million years. Go! And we waiting for the sounds of the bells.

Published in section D2 of Deia.

Gai honi buruzko eduki gehiago

Elhuyarrek garatutako teknologia