Blue treasure to protect

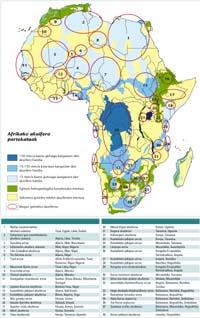

The meeting was organized by the UNESCO Office for Accra and the International Association of Hydrologists (IAH) in collaboration with the Dutch International Groundwater Resource Assessment Centre. The information collected so far was analyzed and the last data collection was prepared for the regional inventory. Once completed, the inventory will be located in the database of the Geographic Information System (GIS) of transboundary aquifers of the region.

Hydrogeologists Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Togo and Senegal produced a status report based on data and information each provided on shared aquifers. The case of Ivory Coast is typical. It reflects the problems that countries in the region have in protecting this precious resource.

The case of Ivory Coast

In the Gulf of Guinea there are two shared aquifer systems with two large sedimentary basins: Basement Basin and Burning Basin. The Tano basin extends from the coastal town of Fresco in Ivory Coast to the town of Axim in Ghana, and the aquifer system covers 2.5% of the lands of Ivory Coast. In the Tano basin there are three types of aquifers. Quaternary aquifers (under 1.8 million years) have a high risk of contamination due to the proximity of the surface of the aquifer system to soil level. The second class is Miopliocene (5-8 million years) or terminal continental aquifers. One of them supplies drinking water to Abidja, the largest city in the Ivory Coast, and the surrounding regions. The third type of aquifer is that of the Upper Cretaceous (94 million years), which is the one that exploits the Société Africaine d'explotation d'eau Minérale. It is the most mysterious of the aquifers, since its geometry, volume, level and length are unknown.

As in Abidja, most of the major cities of the Ivory Coast are located on the coast, including the Bono and the Aboisso. In addition, the region has numerous industries dedicated to the manufacture of pineapple, rubber and palm oil, as well as the gold mine Aboisson Afema. They all consume large amounts of water. And they cause contamination.

In groundwater studies in the Abidjan area, for example, it has been observed that the concentration of nitrates (NO 3 -), ammonium (NH 4 +) and aluminum (Al 3+) in the plateau, Adjamen and western area is too high, according to the drinking water standards of the World Health Organization (WHO). This chemical pollution is due to the use of pesticides and fertilizers on land -- fishermen are also contaminating ponds with pesticides -- even though other ponds have been contaminated by gold mining, including Ghana's Afema Lagoon, located next to it, and Aby Lagoon. In any case, regardless of source, contamination of surface waters with chemicals and household waste poses a threat to people's health and water biodiversity.

The Ivory Coast currently has 18 million inhabitants, half in urban areas, and if this figure is estimated to grow by 2% annually, it will reach about 24 million inhabitants by 2025. Also in Abidjan a strong population growth is taking place (in 1999 it was considered 3.2 million people) and the aquifer of the city is drowning, due to factors linked to the rapid urban process: the construction of buildings and infrastructures on land previously covered with vegetation makes the soil waterproof to rain. If we add that they occupy the soil anarchically with the houses of the neighborhoods, it is increasingly difficult to access the water wells to control the groundwater of the aquifer and facilitate the recharge of the aquifer. In addition, since there is no water treatment or waste disposal system, wastewater is poured directly into rivers and other surface waters, contaminating the aquifer also the city's external agriculture.

Another serious problem is salt water intrusion. This may be due to a high presence of chlorine in the coastal aquifer. In fact, excess chlorine has forced the population to abandon several wells. Specifically, hydrologists have detected this phenomenon beyond Jacqueville, the plain of Abidjan and the east of the Adiaké region.

In short, the main problem is that the state legal framework is not adequate. Laws dealing with the environment, water and mining sectors have been developed but have not yet come into force. A number of legal water resources have been confirmed in the Ivory Coast, but they focus mainly on marine and surface waters.

Early warning system

In 2002, the UNESCO Nairobi office and the United Nations Environment Programme launched a project to assess the impact of pollution on aquifers in eight other major cities in Abidjan and Africa. The cities analyzed were: Dakar (Senegal), Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso), Bamako (Mali), Cotonou (Benin), Keta (Ghana), Mombasa (Kenya), Addis Ababa (Ethiopia) and Lusaka (Zambia).

The project has developed various methodologies to assess groundwater vulnerability by identifying pollution hotspots and major threats. An early warning system has also been established. This system, made up of the network of African scientists, is raising awareness about the risks of waste dumping and similar activities, both in the public and private sectors, with decision-making capacity. "We were looking for a solid control system," says UNESCO program expert Emmanuel Naah, "in order to give prior warnings to legislators and water managers to act in time against pollution." The project is being further developed in line with the assessment recommendations of the workshop held in Cape Town (South Africa) in November 2005.

Compliance with legal vacuum

The description of transboundary aquifers is scientifically difficult, and political factors can further hinder the process. Governments often do not admit that in other countries the aquifers they use to obtain drinking water and to water. In addition, although there are increasing international standards and agreements on shared rivers, they do not apply fully in the case of aquifers.

Also, until recently, international legislation paid little attention to groundwater and transboundary aquifer systems. The only global agreement on water use, approved in May 1997, considers groundwater only when linked to surface water, as in most interstate treaties and transboundary water agreements.

The draft articles contain, on the one hand, the principles of international water law, wise use and the non-condition standard. It includes the general principle of international law, the obligation to cooperate and, in practice, the periodic exchange of data in the case of transboundary aquifers. On the other hand, specific principles of management of transboundary aquifers such as control, protection and conservation, and cooperation with developing countries directly or through the competent international body are codified.

The Shared Aquifer Management Entity is promoting the development of Plans by governments, as well as the creation of Commissions for the joint management of shared resources with the environment and environmental protection. There are also plans for the implementation of legal agreements to improve aquifer protection.

Source: UNESCO. A blue goldmine in need of protection, A World of Science, 5. vol. No. 3, July-September 2007 (http://www.unesco.org/science/)

Article translated and adapted by Elhuyar with the authorization of UNESCO.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian