Andrés Urdaneta, father of the return trip

Thanks to this problem, Elcano and the Victoria crew completed the first round around the world. Magallanes, head of the expedition, did not want to go from the Philippines to the west to return to Europe. Back, I wanted to sail to America and make a trip to the East to return home. But then it was impossible to cross the Pacific to the East and they had to continue to the West until they completed the first tour around the world. The first navigator to overcome the Pacific barrier on his trip to the East was Andrés de Urdaneta, approximately 40 years later.

The Polynesians sailed through the Eastern Pacific long before Urdaneta. They colonized Easter Island and Hawaii from Oceania. This trip was supposedly from the south and on small boats. It is very difficult to know them, but it is very possible that indigenous people living in the Pacific know how to make the trip to the East. Historians believe that Urdaneta himself had a relationship with the indigenous people of the Philippines and that they talked about navigating the Loaysa expedition.

Loaysa Expedition

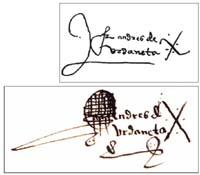

On July 24, 1525, Charles I sent an expedition to the Moluccas Islands under the command of Commander Fray García Jofré de Loaysa. Seven ships left, one of them under the responsibility of Elcano, Sancti Spiritus, who was on the Urdaneta boat. It is not very clear what the role of Urdaneta was. Some say he was raised from Elcano, but it doesn't seem to be true. In that expedition Elkano died and his last will was collected and signed by Urdaneta, a servant who could hardly do it.

Interestingly, on that expedition Elkano and high-level sailors died, including Loaysa himself, and not mere sailors. The reason is explained in the writings of Urdaneta. They were traveling on six boats and, at a time of the trip, all the captains and officers gathered and celebrated a meal; they ate special fish and became intoxicated. The symptoms of poisoning were noted by Urdaneta, which allows some writers to claim that the disease was an inquiry syndrome. Urdaneta studied the disease well from a scientific point of view and made everything very clear.

Urdaneta and the survivors spent a lot of time on the Moluccas. Urdaneta himself spent nine years there and knew well the area, its currents, etc. He was with people there and was getting all the information. In addition, it had a great ease for languages, so historians believe that their relations with indigenous people were through it. They returned to Europe around the world, but Urdaneta, while in Moluca, may have gained experience and information to sail the Pacific once again.

Back to the sea

It seemed that the next opportunity was coming from the hand of the conqueror Pedro de Alvarado, who invited Urdaneta to an expedition through the Pacific. While Urdaneta was in Mexico, Alvarado died and Urdaneta lived there for the next thirty years. For historians it is dark years, because there is not much information about the life of Urdaneta at that time. However, it should be noted that in 1553 he entered a friar.

Years later Urdaneta had the next opportunity to return to the sea. Philip II called him for an expedition to the Philippines. The king's concern was to investigate where the antimeridian was: According to the Treaty of Tordesillas, the newly discovered land located to the west of a meridian would be for Castile and the one to the east for Portugal. In this way, Castile would absorb most of the territories of America. But the meridian also distributed the lands across the world. Philip II requested with this excuse the ownership of the Philippines (and acquired it, so the islands have that name). However, they could not determine where the antimeridian was.

Historian Artetxe wrote that Urdaneta told the king that according to his calculations the Philippines belonged to the Portuguese. I needed some excuse to go to the Philippines, because actually those islands are in the area of Portugal.

Return trip

The return trip was not easy. Five expeditions attempted to make the trip before Urdaneta. But in the face of storms, currents, wind, diseases… all previous expeditions failed.

Urdaneta managed to make that trip taking a very rare path from the point of view of those of that time. He moved away from the equator to the north to avoid adverse winds and currents and returned to America from the maximum circle, the shortest road. Historian José Ramón de Miguel says he surely wanted to go from the same latitude of Toledo and got it with astronomical measurements. When he was at a latitude of about 39 degrees, Urdaneta carried out rare maneuvers (travel on the map in the form of M), supposedly meaningless, but very understandable considering the need for cross-navigation. Thanks to this, he trapped the Kuro-Shivo current and was able to travel eastward. He reached the coast of the California area and then returned to Acapulco in October 1565. Return trip XIX. Until the 20th century it was the main reference to cross the Pacific to the East. Subsequently, the technology of navigation allowed other ways.

Andrés Urdaneta died in Mexico in 1568 (historians are convinced of this). The history of navigation is reminiscent of its return journey, but the history of science should also be remembered for many other things. Among others, for the written documents he received. He made detailed calendars and reliable descriptions, essential documentation for anyone who wants to know the science of yesteryear.

Special thanks to Goyo Lekuona and José María Abedul. The article and many other information about Urdaneta can be found on the website of the radio program Norteko Ferrokarrilla: www.elhuyar.org/norteko_ferrokarrila/

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian