Interior of Txingudi Bay

Readers of the magazine Elhuyar will remember that the first article on Txingudi was published in January 55, 1992, in which the Txingudi schism was described in depth. In this first article, although only part of this privileged environment was discussed, it became quite clear that the ecological attractions of Txingudi do not end in their schism, and that is precisely what has encouraged me to write this second article.

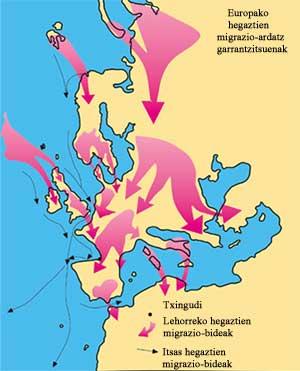

On this occasion, leaving aside the estuary, the marsh, the cliffs and the fields of the Bidasoa River, I will take care of the interior area, where there is an ecosystem of great importance: that of the dunes. Although the situation of the dunes is not as serious as that of the marshes in Euskal Herria, we cannot be optimistic about their future, especially in these areas and on the beaches where human pressure is enormous.

In Txingudi fortunately we have witnessed this ecosystem, although the situation is very serious. For this reason, I would like that through this article, in addition to explaining the ecological importance of this aspect, the reasons for the movement created for the conservation and recovery of Txingudi Bay are better understood.

Interior of the bay

As in all other aspects of the lower coast of our coast, in the bay of Txingudi there is a large accumulation of sand thanks to the numerous materials eroded and transported by the sea. Although the entrance to the bay was closed by a sand bar as a result of this process, two garrisons currently built by the municipalities of Hondarribia and Hendaia have broken this old obstacle, giving solution to navigation problems.

In any case, as in all estuaries, in Txingudi the contributions are bilateral. On the one hand, the materials provided by the river that have given rise to the ecosystems of the marshes, and on the other, those coming from the sea, which have given rise to the creation of dune ecosystems.

Due to the different influence of sea tides in each area, the amount of these materials from the bay bottoms is also different. Therefore, while in the region furthest from the sea arids predominate, in the closest to the sea sand is the majority component. Between these two extremes there are numerous transitional funds. This wealth of background is one of the main engines of the wealth lived in Txingudi, which offers numerous ecological niches to the populations of molluscs and annelids, base of food chains.

Molluscs

As in the previous article I just mentioned these groups, this time I would like to talk more, since the wealth of molluscs of this bay is evident. Just a few years ago, commissioned by the Basque Government, in a study conducted to analyze the commercial value of the mollusks of our rias, the Hondarribia estuary, along with that of Mundaka and Zumaia, appeared as an area of high maritime value.

While in Zumaia eight species of molluscs were mentioned and in Mundaka fourteen species of molluscs, twenty were described in the estuary of Hondarribia, of which it was recognized that eighteen could have commercial value.

All these species have been divided into two main groups, according to the substratum in which they live attached: rocky and soft bottoms. Among the first are the different species of mussels and oysters that inhabit the middle and outer zone of the estuary, from the middle level of the tide to a depth of approximately three meters. The abundance of these organisms in Txingudi must be associated with their eating habits, since by filtering water they feed on small living beings of plankton, for which they need mouths and similar places of great current.

Among the soft substrates, the different species of cockles and clams stand out. One of its most outstanding characteristics would be the existence of suspensory eating habits, that is, the capture of organic matter on the sediment through its siphons. However, although the form of food is similar, it is not exactly the same, so each species is in specific areas of the rías. The cockle, for example, appears in pawn or sand substrates, in the central part of the estuary. For its part, the clam, despite living like the previous one in the center of the estuary, needs substrates consisting of gravels and sands or sands and arid.

It should be noted that these soft substrate species require special environmental conditions for their survival, since the current cannot be very hard (so that it does not carry it) or very weak (so that the sediment does not accumulate above). Therefore, both intense rainfall and strong sedimentary movements cause high mortality rates in the populations of these species.

Although the extension of other species of molluscs that we can find in Txingudi is not comparable to the previous ones, they have a special value for their scarce presence in the rest of the rías of the Basque Country. Among them are the curved date (Ensis ensis), the large date (Ensis siligua), the striated date (Solen marginatus), the flap (Patella sp. ), snail (littorina littorina), candelux (Durex trunculus), etc.

However, although the situation of these mollusks is relatively good in terms of diversity and quantity, we cannot be optimistic about their health, since water pollution directly affects these filter organisms and even more so the heavy metal contamination of the water in Txingudi Bay. The introduction of these heavy metals inside the body prevents its extraction, since metabolic pathways are not able to expel these foreign elements, but accumulate inside the body.

In addition, as these living beings are the basis of the food chain, this effect extends to all components of the chain. Higher in the chain, higher concentration.

However, for these macroinvertebrates a small window of hope has been opened with the approval of the sanitation plan of Txingudi Bay, which will paralyze this dangerous contamination of heavy metals by itself. With sand movements we cannot say the same thing. The institutions have expressed no intention of paralyzing the residual extractions carried out inside the bay, despite the fact that the lack of legality of this activity has been demonstrated.

Dunes

However, this macroinvertebrate wealth is not the biggest attraction in the area. In Txingudi, for example, there are still witnesses of the dune ecosystem, both on the beach of Hondarribia and on the beach of Hendaia in the place called Xokoburu, which to date has remained quite well.

Thanks to the northwest wind currents that dominate our coasts, the materials eroded by the sea accumulate in areas of low coast forming our beaches. The conditions of these means are very harsh for living beings. Therefore, the native vegetation has achieved special adaptations to live in these conditions. On the one hand, these areas are areas of strong wind, which not only prevents the presence of high altitude vegetation, but the loose sands transported by the wind cause an erosive effect on plant tissues.

On the other hand, the presence of numerous pores between the grains of sand accumulation causes rain water to leak rapidly. This and the intense heat that usually exists in these areas make the surface layer dry.

Another factor to consider is the high salinity of the environment, which causes problems of osmosis in the vegetation (intracellular water, tendency to extraction to compensate for the difference of salinity in the outside).

To live in these harsh conditions, the dune plants (psammófila vegetation) present a series of adaptations:

- Radical systems of great development: by means of which, in addition to obtaining the water so scarce in surface in

these areas in low layers, they get a solid fixation to avoid the winds. - Fatty tissues: the cells of these tissues are adapted to contain liquids with high salinity. In this way they have achieved the ability to use atmospheric humidity, facing the aridity of the earth. Among the species that explain this adaptation are Honckenya peploides and Cakile maritima.

- Abundance of hair: this adaptation allows some plants to reflect the incident light, reducing evapotranspiration (amount of water that is returned to the atmosphere through plant transpiration). The most abundant species in the Basque Country that has acquired this adaptation is the herb of Medicago marina, which appears in the dunes.

- Finally, it is worth mentioning that other herbaceous species have developed other adaptations to support continuous burials and burials. Some grasses of the genus Elymus have developed stem and leaves. Specimens of Pancratium maritimum, however, have developed bulbs (transformed underground buds for reserve) and tubers (stem thicknesses rich in reserve substances).

As a culmination of the description of these ecosystems I do not want to mention the following plant species that appear in the dunes of Txingudi: Euphorbia paralias, Eryngium maritimum, Calystegia sp, Soldanella sp, etc.

Birds

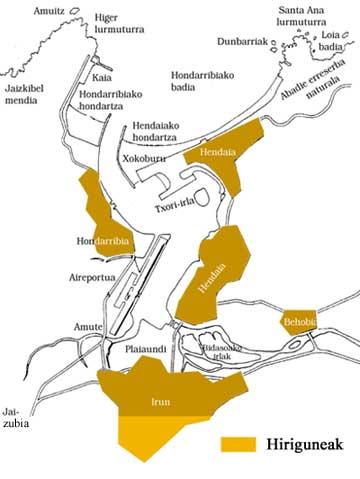

But as I commented in the previous article, the most spectacular attraction of Txingudi is its poultry wealth, since it is located in an important migratory axis. Therefore, in this area of the bay there are also numerous birds, especially in times of migration.

Perhaps at this point it would be better to explain more broadly the importance of Txingudi in bird migrations, since in the previous one I only mentioned it. It must be said that when food begins to decrease, nesting birds in Northern Europe begin the migration of the escogena, a food evolution that usually takes them to North Africa. To carry out this trip in Europe there are three main axes:

- Oriental: Crossed by the Balkandar mountains and Turkey.

- Central: Tour Italy and Sicily.

- Western: The one that crosses the Iberian peninsula.

In the latter, the Pyrenees become an impassable obstacle. The importance of Txingudi, which is the western end of the Pyrenees, is what must be done to overcome this barrier.

Therefore, the birds passing through Txingudi are: Scandinavian peninsula, Holland, northern Germany, Denmark, British islands and western France. Add the seabirds that migrate around the coast.

This long migration generates great energy losses for birds and at this point we will find one of the main reasons for the conservation of estuaries, where many birds find the rest, protection and food they need so much.

On the other hand, although the biggest migratory episodes occur in spring and autumn, time is the last motor of these displacements; each bird species has days or weeks to carry out the migration. Therefore, the most suitable time for those days will be chosen to migrate.

Therefore, in all the winds of the south and of the sky, they are usually days of great pass, while in the days of storm of the northwest wind or of the northwest wind it is easy to see birds of pelagic behavior next to the coast.

During these days, Cape Higer is the ideal place to study the migratory habits of all these birds that approach the coast in search of better conditions and protection. Among them are the duck (Melanitta nigra), the ditch (Sula bassana), the moñudo cormorant (Phalacrocorax aristotelis), the puffin (Fratercula artica), the págalos (Stercorarius sp. ), candle (Puffinus sp. ), etc.

I would not like to conclude this point without mentioning what happened in 1984, that is, due to the storm of winds of Hortentsia, we had the opportunity to see many species of birds of difficult presence in our coasts. Among them: The Sabine ancheta (Larus sabine), the various stormy birds (Hydrobatidae), some western birds (Phalaropodidae), etc.

As for the interior of the bay, the birds observed during the migration belong to species of swimmers and faraway. In Txingudi are frequent both Gaviidae (Colimbos), Podicipitidae (Bats and Brezales), as anatidae (Eider, Somateria mollisima; Sierra Media, Mergus serrator), Phalacrocoracidae (Cormoranes) and Ninsterae (Enaras de mar).

On the beaches, in addition to anatides, there are numerous limicolos, where there are the necessary foods to complete the diet. Therefore, in times when human pressure is not high, it is frequent to see ankles on the beaches of Txingudi (Calidris sp. ), chorlitejos (Charadrius sp. ), stone revolution (Arenaria interpretes), etc. Nor should we forget the seagulls and marine swallows that use these areas to rest. At this point highlights the espadrille that reverses in Txingudi (Plectrophenax nivalis), since it finds its preferred area in the dunes.

I would not like to end this article without showing my disagreement with the politics they carry in Txingudi Bay. This reminds us of the destruction of the development policy and the natural heritage that has caused so much damage to the environment in Euskal Herria. Proof of this are the pharaonic projects for the sports docks that are presented for both Hendaia and Hondarribia. As is normal in our authorities, these two projects have not carried out any type of environmental research, without taking into account the ecological values of this privileged aspect and the strong movements against these projects that have emerged in both countries. If our society does not change its vision of the environment definitively, what is written here will be incredible for generations to come.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian