Sailing is a matter of strength

The world of browsers is very peculiar; seen from the outside, it is not easy to understand neither the language, nor the concepts, nor the navigation techniques that they use normally.

They do not say 'left' or 'right', but 'abbabor' and 'istribor'. But be careful. Abanto and starboard are left and right if we look towards the bow and vice versa if we look towards pop. However, many times it does not matter the left or the right, but where the wind blows. They then use 'haizealde' and 'haizebe' (windward and leeward, respectively). However, all these concepts are more complex than the left or the right. And it is logical that it is so because the wind to navigate marks the references.

Even when the boats are tied, the wind marks the references. This is evident when they are out of port protection. The bow of the boat, attached to a buoy, indicates where the wind comes from; when there is northern wind, the boat is "looking" to the north, when there is southern wind, to the south, etc.

Also, if the motto of a sailboat is released, the boat turns to place the bow towards the wind side. Those of earth need a vane to see where the wind comes from, but the browser just has to drop the motto, turn off the engine or stop paddling. The boat itself will teach you where the wind comes from. Modern ships have a lot of tools to know, but, although electronics fail them, they do know how. And knowing where the wind is blowing is very important for those who want to sail, even if it is sailing, rowing or motorbike. The wind is a reference in the sea.

Candles and wings

Of course, in sailing boats the wind is the cause of navigation. But that doesn't mean the wind sends where the ship will move. Browsers do not need favorable wind to travel to a direction.

No. They only need wind. Without wind there is no movement, but if

there is wind, it is indifferent if it is wind of direction. If you hit the vessel by the stern, you will push the sailboat forward, which is known as going aft. But although it sounds on the other hand, there is no problem. In short, sailing is art, art of harnessing the strength of the wind.

The sailboat uses candles to take advantage of the wind, but not just the candles. A kind of wing located at the bottom of the hull is also essential for sailing the sailboats. This south is called keel. The keel is not an authentic south, but it is often compared to the wings of the planes, since the sailing forms of the sailboats and planes are similar in part.

Imagine a plane inclined ninety degrees south and immersed in the water to half. One of the wings would be out of water and the other under water. If the underwater bottom was much lower than the air, the result would be a sailboat. Obviously, in this comparison they do not take into account the buoyancy, lightness of the upper sail, nor the presence of more than one candle in the air, but it is a useful comparison to explain the relationship between forces and navigation.

Newton and Bernouilli

This relationship, logically, is based on Newton's laws that analyze the origin and influence of forces. And one of the things they say is that there is no acceleration without force. The shutdown stops if it is not activated with force. Likewise, the one who moves at a speed will advance at that speed until it is affected by a force, the braking force will slow down, the acceleration force will accelerate and other forces will change the direction of the movement. Note that for physicists the change of meaning in a movement is a type of acceleration, that is, the influence of a force.

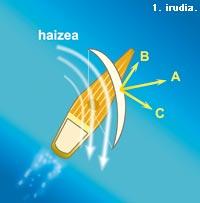

In the case of sailboats, the sail itself changes the direction of the wind. The wind attacks the sail from one angle and leaves another. In fact, the candle is a curved surface, driven forward by the pressure difference it exerts on the air. In short, in the convex part of the candle moves faster than in the other, and according to the principle described by the Dutch Bernouilli, this influences the air pressure, since in the fast moving zone the pressure is lower. The pressure difference generates a force, low to high pressure.

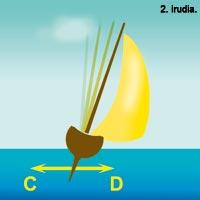

This force is represented with the letter A in Figure 1. It is the law of Newton's action reaction, the action is to divert the air in a sense and the reaction is to move the sailboat in the opposite direction to that deviation. The force A of the image, however, does not have the same direction as the movement of the sailboat. For that is the keel. The keel does not drop the container. Stop in the direction perpendicular to the movement of the sailboat. And because of this keel effect, the boat has no other solution: it has to navigate forward.

For the calculation of this forward motion, physicists divide forces. The truth is that any force can be the sum of other forces. The same is represented in the figure. As indicated, force A is due to the wind on the sail and can be considered as the sum of both forces, B and C. Force B pushes the boat forward and force C is perpendicular to the keel. The keel generates a force D to compensate that C and finally the container advances

The function of the keel is to keep the container upright, so it exerts a force against water. Usually the mast of the container is very close to the vertical position, but not always.

In the most spectacular images the sailboats sail very tilted. This is what happens when you sail against the wind, very close to the direction of the wind; the force on the sail is very large and the key cannot resist at all. In this case the container reaches maximum speed. It can go faster than when you go in stern.

Apparent wind

However, it is not easy to keep the container at the angle that reaches maximum speed. Getting the best out of the wind is art, because on the one hand it changes the strength and direction of the wind every time and on the other hand it must be taken into account that the wind that perceives the browser is not real. The wind is perceived as a consequence of the navigation itself, that is, of the movement itself.

It's like riding a bike when there's no wind and feeling air, the air isn't moving, but the bike is, and what goes on is the feeling that there's wind. In the sailboat the same thing happens, and also that feeling is combined with the real wind, of course, if the sailboat is moving there is real wind. This is called apparent wind.

But the boat is not driven by the apparent wind, that wind does not participate in navigation, it is only a consequence. In a way, the real is a combination between wind and speed fraud. Precisely, in order to navigate

well, we must recognize where the real wind comes from. As already mentioned, there are several tools that help to do so, and in addition,

releasing the sail, the bow of the

boat points towards the wind.

Browsers know perfectly well the maneuver of release of the sail and other thousand matters of the physical base of navigation. Surely these questions will not be exposed in the language of physicists, but in nautical. And they may not mention Newton or Bernouilli, but they apply their laws on board.

Surfing is a matter of strength, no doubt, but browsers have turned it into art. Bear in mind, moreover, that what is written here has been but an approximation. From this starting point to the sailing is long.

For the wind against the wind

The sailboat cannot sail directly against the wind, but it can approach that direction. You can sail about thirty degrees from the direction of wind arrival. Closer to the direction of the wind, the sail loses tension, begins to dance, the vertical mast is placed and the boat stops with the bow towards the wind. However, if the limit angle is not exceeded, the fastest possible wind speed is reached. Of course, if you want to sail directly to the wind, you have to change the meaning of the sailboat and make zigzag.

The limit angle is thirty degrees for each side of the wind direction. This means that in an interval of sixty degrees you cannot navigate. But three hundred degrees remain to catch the wind's thrust.

Faster navigation

The longer it is, the faster the sailboat can go, as the speed depends on the length of the flotation line. And that's why experts calculate it. By multiplying the square root of this length by 1.34 you can calculate the maximum speed that can reach a container, approximately. The formula is simple but allows an acceptable approach.

The calculation is done on the feet to extract the speed in knots. For example, in the case of a ten meter sailboat, the length is 30.48 feet and the result of the speed is approximately 7.4 knots. (For those on land it must be said that when you say knot you mean sea mile then, that is, 1,852 kilometers per hour. Therefore, 7.4 knots are approximately 13.7 kilometers per hour). Logically, the result of this operation is an approximation, limited by wind and browser skill.

The calculation has been based on the length of the flotation line, but finally the key is in the water. The sailboat cannot sail faster than the swell it generates when sailing. In small sailboats, for example, it should be noted that a boat generates two waves when sailing,

which generates the bow and another wave near the pop. The maximum speed is reached when the distance between both waves coincides with the length of the flotation line.

If for a moment it exceeds that speed, the boat's pop drops into the water and the bow stays in the air. As a result, the flotation line decreases and the container loses speed.

However, there is a way to navigate at a speed higher than the estimated maximum: surfing on a wave. But this requires skill and speed is not long.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian