Historical evolution of body morphology

Human populations have a great morphological variability, both within the population and between populations, due to the long evolutionary past, genetic heritage and adaptations to the environment. Besides the monocygothic twins, there are no two equal persons; however, the morphological similarities are common among individuals of the same family and of the same people, who share the same genetic or similar heritage, or both. Human morphology is very peculiar; we are the only animal with the ability to stand constantly on the two legs (bipedalism), we have a large skull compared to the total size of the body, a more or less flat face as the bone of the face has been reduced, and the nose can be considered as an exclusive feature of the human being.

The morphological differences (sexual dimorphism) between men and women are manifested from puberty and, before this stage, the phenotypes are quite similar between boys and girls, apart from the secondary sexual characters. As it advances in adolescence, androgens cause fats to decrease in men, and muscle tissue to develop until the neck and shoulder are spread -- bone growth of the upper part of the chest also influences. In women, on the other hand, adipose tissue goes to the thighs and to change, which makes the female figure have greater glories and wider hips. In the woman's fat model (ginoid or "pear form"), fat is usually found in the lower part of the body, buttocks, thighs and, in general, in the extremities. This is the pattern of the reproductive period and changes towards the fifth decade of life, since the levels of estrogens and the lypolitic activity of the fat cells of the abdomen decrease, which causes a change in the distribution of the fat that goes from the ginoid model to an intermediate model until reaching the android model of menopause (apple shape).

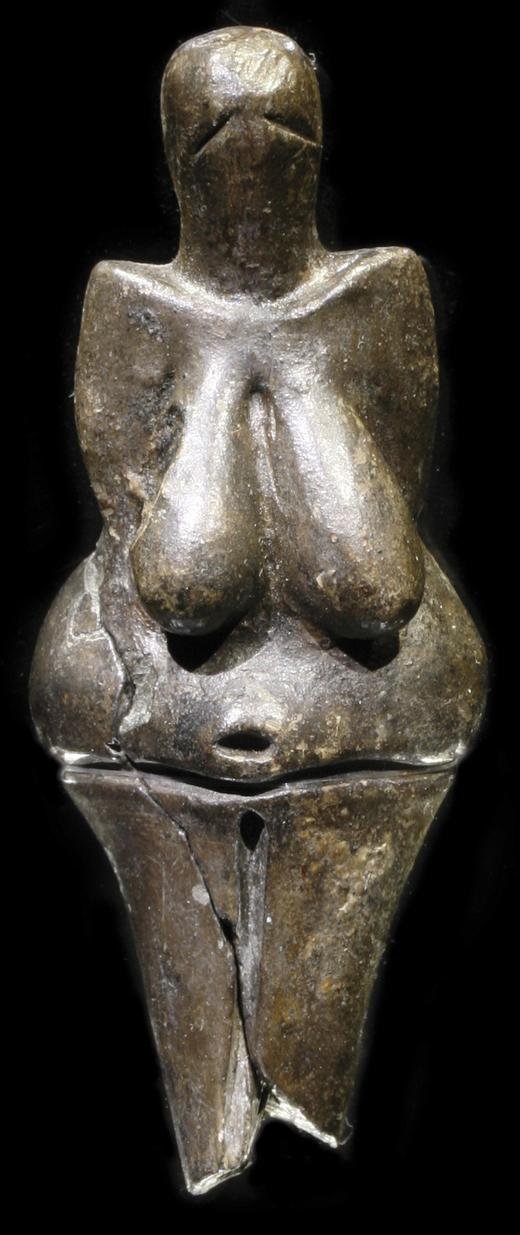

The human body has been adorned (and made) in most cultures, and its representations have always been historical (paintings, sculptures and, more recently, photographs). Schematic representations of the human body also appear in prehistory. The sculptural degree of Venus of the Palaeolithic, which shows thick bodies, thick belly and imposing breasts, morphology that has often been considered as an indicator of the fecundity and survival of the group, is striking.

Our species is the result of biology, culture and social way of life, and has been able to change its morphology, within the limits marked by genetics, endowing it with ethical and aesthetic endowments in terms of time and space. This is what is observed in the so-called rules of beauty, which from the Western point of view have been the most influential in the classical world, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Femininity and friendliness have been represented in different times, times and styles, and the relationship between the form and beauty of the body has been made with the two sexes, but perhaps more often with women, for cultural, social, economic and religious reasons (we cannot forget that in most societies one believes in the dominion and power of man).

In Western society, body transformation activities have proliferated, and many people adapt the body to the demands of social norms. Men are asked to be athletic and strong bodies. Women, for their part, have a social obligation to be always young, so they are subjected to fashion, aesthetic surgery and extreme diets, with the aim of a body model marked by the time and culture: a model of fertility in a steep form (binomial empowering maternity) or an androgynous model (adolescent and slender bodies). It is true that for a couple of decades we have the so-called “obesity epidemic” and are living its consequences both in the health and social spheres. Obesity is recognized as an important health problem and it is urgent to adopt adequate preventive and therapeutic measures. However, because obesity is not appreciated in our environment (although present in other societies and historically), there is a circle of anxiety to lose weight/fat (especially in women) that causes problems of self-esteem and changes in body appearance.

But let's be optimistic. Improvements in health and food have led to changes in the size and shape of the human body, increasing the hope of life. These collective changes are called "secular changes" and have been noted in many countries -- cyclically, sometimes -- in the XVIII. Since the twentieth century. In particular, the peoples of Europe. Since the mid-twentieth century. The nutritional transition experienced until the end of the twentieth century affected the size (and shape) of the human body. They also left a mark on the demographic and epidemiological transition, the first caused a decrease in fertility and the second caused an increase in life expectancy. Today we are more than three centuries, we have more body mass and live more.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian