Error with or without h?

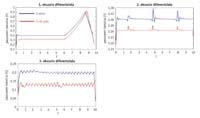

Different error estimation

If a differential equation cannot be solved analytically, it can be solved by numerical methods. The analytical result is accurate, while the result obtained by the numerical method is approximate and is built step by step. The error in releasing a differential equation by numerical method is the difference between the exact and approximate result. A concept that theoretically has no more difficulties than a subtraction, when it must be calculated in practice becomes a complex concept. But what is the problem? We do not know the exact results of many differential equations. Therefore, by ignoring the exact result, it is impossible to calculate the error we are making when using the numerical method. Although we do not know the error, we know that the approximate result obtained using high order numerical methods is more accurate than that obtained with lower order numerical methods. However, whenever a step is taken by the numerical method, a measure is usually used that tells us whether the result obtained in that step is valid or not. What is this measure if we have said that the error cannot be calculated without knowing the concrete result?

The measure used is the estimation of the error. A very useful error estimation is calculated as the difference of results obtained using numerical methods of successive order, based on the elimination of the result obtained by using a numerical method of order ( n+1), which is known as local extrapolation. When we use it, at each step we demand that the difference between the results obtained by two consecutive methods be less than a previously established tolerance. If the condition is met, the result given by the order method ( n+1) is accepted, otherwise it will be necessary to repeat the step operations and test it with another step less than that used previously. If we wanted to use local extrapolation of any of the measurements to be carried out in a laboratory, two measurements of the amount to be measured using two different precision devices would be made. Since the precisions of these devices must be consecutive, when a higher precision device is available, the second one will be the one with greater precision among the devices with less precision than the first. In this way, we would ensure that we are using devices with successive precision. The measure should be repeated until the difference between the two measures is less than a given value and, if the condition is met, the result of the most accurate device will be accepted. As can be seen in the laboratory example, ignorance of the actual result is paid by doubling the number of calculations.

Local extrapolation is therefore a safe but expensive resource at the same time. Since its potential is based on comparing the results obtained with two different methods, it will always mean an increase in the number of calculations. Taking advantage of the certainty of local extrapolation and accepting the increase in the number of calculations, many of the creators or parents of numerical methods have focused on the design of methods that could make this number of calculations not double, that is, they have aimed to give birth to two methods of successive order with the smallest possible differences. In this sense, by using a different set of constants in a single operation, the methods that perform a method of order n or ( n+1) are very useful, since they manage to optimize the difference between two methods of successive order. Example of this are the Runge-Kutta methods introduced. In them, it is sufficient that, in addition to the operations performed to obtain the result by the order method ( n+1), a single operation is carried out to obtain the result provided by the order method n. They therefore offer an economical option to obtain results from different orders. There is only another cheaper option than getting both at the price of one. But that is impossible, because different methods must be differentiated into something.

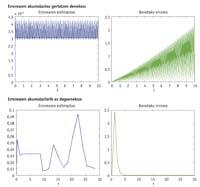

Estimation with h without h

Sometimes the drop in the barrier will not be affected, as there will be estimates that would pass the initial height of the barrier without help. But there will be leaps that cannot exceed the initial height of the barrier and that will be affected by the descent of the barrier. Consequently, the step that should be repeated using another estimate will be considered valid. Repeating a step involves testing with smaller steps, and if the steps are small, more is needed. Therefore, when we use the estimates in which we are lowering the barrier, fewer steps will be taken and therefore greater than those that do not fall. The coin, however, has another aspect, since it may happen that the descent of the barrier does not have the desired result. This can negatively influence the final error and drastically reduce the quality of the approximate result we get. In general, the estimate that is calculated without h will lead to the need to take smaller steps, but the accumulation of real error will also be lower.

Estimation error in h or without h

Differential equations can be rigid or not rigid. The practical definition of the rigid differential equation is that of an equation that must take many steps to an algorithm. Although the word "much" does not indicate specific numbers, 100 steps are not many and 3,000 are many. When the problem is rigid, it is preferred to use an estimation without “h”, since with the estimation with “h” a much better result will be obtained than that obtained with the estimation without “h”. Although the problem is not rigid, the result obtained with an estimation without h will be, in most cases, better than that obtained with h, but the result --difference between both - will not be so spectacular, that is, the additional work that involves the use of an estimation without h in non-rigid differential equations will not generate much brightness in the solution.

In languages it is common for a word to lose or gain the "h" according to the time. Examples of this are the construction of walls sometimes with or without h, or the healing of patients in hospitals with or without h. However, the function or meaning of the words that have stuck or removed the “h” by the time has remained the same. The subject of errors with h and without h in mathematics does not depend on the time: there has always been coexistence between both, and both are necessary because the function of one and the other has never been the same. As we consult in the dictionary whether a word has an “h” or not, to decide whether or not to use an “h” in the estimation of the error we will have to “consult” the problem to be released, since the key to the success we will obtain in the result will be that the estimation of the error has an “h” or not.

Buletina

Bidali zure helbide elektronikoa eta jaso asteroko buletina zure sarrera-ontzian